Georgians Revealed, British Library | reviews, news & interviews

Georgians Revealed, British Library

Georgians Revealed, British Library

An entertaining look in the mirror as middle-class Britain discovers taste and leisure

The Georgians are in our marrow, and two of them in particular. The dawn of the age gave us Handel, who came over from Hanover with George I. Then at the sunset came the ever-exalted Jane Austen, who dedicated Emma in mock deference to the bloated Prince Regent. And in between there are all those elegant terraces in dark-brown brick, desirable survivors of the Industrial Revolution and the Luftwaffe.

As this entertaining exhibition argues, the Georgian age is also the crucible to which the British owe much of their identity. It was in the pre-Victorian century that the middle classes, which nowadays consist of most of us, were invented, and began pursuing their leisurely obsessions – with gardens and shopping, theatre and tea, not to mention celebrity and sex. How to illustrate all of the above at the British Library, which after all contains mostly words? (pictured below, English teapot and cover © Victoria & Albert Museum).

At the heart of this grand tour of the Georgians is the library of George III, displayed in its entirety in the ingenious glass tower running up through the building. Choice examples have been extracted to illustrate the growth of interest in, for example, botany. Huge and handsome tomes - Thornton’s The Temple of Flora and Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands - are both open on pages where tropical plants are ravishingly in flower. Elsewhere the great illustrators of the age are also in abundance: Hogarth prints capture the clumsy English at a country dance; Rowlandson illustrates the perils of travel as a phaeton entering Hackney keels over and decants its passengers; Cruikshank, long before he teamed up with Dickens, turns society gatherings into assemblies of grotesques; Gillray depicts a cockney taking his corpulent wife for a ride along a rutted country lane (for more images see gallery overleaf).

At the heart of this grand tour of the Georgians is the library of George III, displayed in its entirety in the ingenious glass tower running up through the building. Choice examples have been extracted to illustrate the growth of interest in, for example, botany. Huge and handsome tomes - Thornton’s The Temple of Flora and Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands - are both open on pages where tropical plants are ravishingly in flower. Elsewhere the great illustrators of the age are also in abundance: Hogarth prints capture the clumsy English at a country dance; Rowlandson illustrates the perils of travel as a phaeton entering Hackney keels over and decants its passengers; Cruikshank, long before he teamed up with Dickens, turns society gatherings into assemblies of grotesques; Gillray depicts a cockney taking his corpulent wife for a ride along a rutted country lane (for more images see gallery overleaf).

Where Regency artists get to work the tone inevitably turns irreverent, even scurrilous, but for the most part the Georgians keep their minds on higher things. This was the age in which taste percolated down from the ruling classes so that Wedgewood and Chippendale became suppliers to right-thinking households and the Adam brothers put together a fetching catalogue of interior decoration (pictured above left, Thomas Chippendale. The gentleman and cabinet maker’s director. London, 1754 © British Library Board). Meanwhile refinement sprouted on the feet of the Georgians – some splendid slippers come from the Northampton Museum – even the chaps have ribbon for laces (see main image).

Where Regency artists get to work the tone inevitably turns irreverent, even scurrilous, but for the most part the Georgians keep their minds on higher things. This was the age in which taste percolated down from the ruling classes so that Wedgewood and Chippendale became suppliers to right-thinking households and the Adam brothers put together a fetching catalogue of interior decoration (pictured above left, Thomas Chippendale. The gentleman and cabinet maker’s director. London, 1754 © British Library Board). Meanwhile refinement sprouted on the feet of the Georgians – some splendid slippers come from the Northampton Museum – even the chaps have ribbon for laces (see main image).

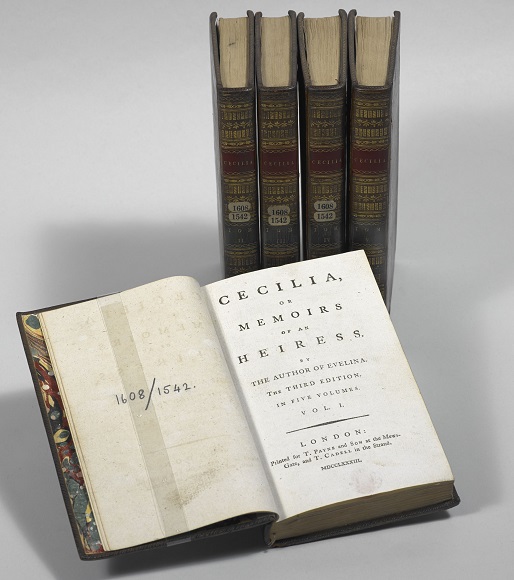

This is the story in which wealth as well as taste spread away from the palaces and grand country seats conjured up by the great architects and landscape designers of the age (Soane, Repton, and Nash's Brighton Pavilion designs are all mentioned in dispatches). The opening room has portraits of the four Georges alongside a timeline of key political events, but kings, lawmakers, revolutions and conquests all stay in the background. As do the thinkers of the age. The only sign of Swift is his Polite Conversation, alongside Lord Chesterfield’s advice for his son. Fanny Burney's Cecilia may be here, but Austen is represented by her writing desk and spectacles, emblems of a life spent in a typical middle-class drawing room. (Pictured above right, Fanny Burney: Cecilia. 3rd ed. London, 1783 © British Library Board).

This is the story in which wealth as well as taste spread away from the palaces and grand country seats conjured up by the great architects and landscape designers of the age (Soane, Repton, and Nash's Brighton Pavilion designs are all mentioned in dispatches). The opening room has portraits of the four Georges alongside a timeline of key political events, but kings, lawmakers, revolutions and conquests all stay in the background. As do the thinkers of the age. The only sign of Swift is his Polite Conversation, alongside Lord Chesterfield’s advice for his son. Fanny Burney's Cecilia may be here, but Austen is represented by her writing desk and spectacles, emblems of a life spent in a typical middle-class drawing room. (Pictured above right, Fanny Burney: Cecilia. 3rd ed. London, 1783 © British Library Board).

Everywhere we meet the newly well-to-do, busy at their tea-drinking, quadrille-dancing and riotous theatre-going, making music and devouring the newspapers, and enjoying a game of cards or billiards (treatise supplied). Their entertainers are Grimaldi the clown and Garrick the tragedian. They sneak their vicarious thrills in shuddering at Jack Shepherd the highwayman, gossiping about Scrope Davies the absconding rake and debtor, tut-tutting at Elizabeth Chudleigh. In 1749 this proto-pinup turned up at a masquerade wearing next to nothing (see gallery overleaf) and nearly 30 years later returned to the headlines when she was tried for bigamy.

These Georgians weren't entirely blameless. There is evidence of a good deal of gambling and whoring. Harris’s Life of Covent Garden Ladies, published in 1789 and updated four years later, advises on the services available to gentlemen of leisure. Miss All-s-n of No 4 Glanville Street, is “now just in her prime… rising seventeen… can trot, amble, & even gallop, if required.” In the entry for Miss Char-rl---n of No 59 South Moulton Street there is much laboured punning on the word “bush”. Both ladies are complimented on their teeth.

What with sugar pouring into the thriving port of Liverpool, the teeth of every Georgian were now under threat. The traders listed in Grove’s Liverpool Directory, 1781, gestures at the wealth accruing elsewhere in the kingdom. This is a rare glimpse of the provinces. There is also a perspective view of a charming terrace in Birmingham, and a map of Midland canals. We spot the adventurous English being guided round the terrifying sublimities of Wales by Thomas Pennant. Then, once the Napoleonic wars are done, a French cartoon from 1815 lampoons the disgruntled English abroad - the dog bringing up the rear carries a knapsack (pictured below, Famille anglaise en voyage, 1815 © British Museum).

But this is overwhelmingly a London narrative (and that also goes for the museums supplying the exhibits). Dr Johnson’s famous phrase adorns a wall, including the less quoted second half: “for there is in London all that life can afford.” Despite the narrow dimensions of the city – a city map shows that the West End parks are themselves surrounded by open fields – any modern middle-class Londoner would feel all too at home here. This is a place arranged for the pursuit of pleasure and the acquisition of wealth - with perhaps half an eye on charitable deeds at Coram’s hospital or Farringdon Ward School, illustrated by two statues of a boy and girl representing diligence and sobriety.

But this is overwhelmingly a London narrative (and that also goes for the museums supplying the exhibits). Dr Johnson’s famous phrase adorns a wall, including the less quoted second half: “for there is in London all that life can afford.” Despite the narrow dimensions of the city – a city map shows that the West End parks are themselves surrounded by open fields – any modern middle-class Londoner would feel all too at home here. This is a place arranged for the pursuit of pleasure and the acquisition of wealth - with perhaps half an eye on charitable deeds at Coram’s hospital or Farringdon Ward School, illustrated by two statues of a boy and girl representing diligence and sobriety.

The one thing missing, beyond only the most glancing allusions to the slave trade, is much in the way of reference to the underclass. After all, apart from the consolations available to sots and drunks in The Comforts of Life, they didn’t have time to enjoy themselves, or the means to leave a record of their lives on paper. The status quo is best illustrated by the batting order for Mary-Le-Bone in 1792, quoted in a compendium of cricket scores. Opening the innings are the Earl Winchilsea and Hon E Bligh. Another Hon bats at three and only then are the commoners, some not even afforded initials, allowed their turn.

Overleaf: browse a gallery of images from the exhibition

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment