'Books have been my life': Doris Lessing | reviews, news & interviews

'Books have been my life': Doris Lessing

'Books have been my life': Doris Lessing

A lively encounter with the 2007 Nobel Laureate for Literature, who has died at the age of 94

Doris Lessing’s storm-tossed life would make a stirring biopic. She spent her early years on an isolated farm in the Southern Rhodesian veldt, abandoned the children of her first marriage to take up with a German communist refugee during the war, then left for London, became a single mother with a third young child, and had her lifelong battles with her own mother. Much of it is recorded in the Children of Violence tetralogy about her literary alter-ego Martha Quest.

Eventually there were more than 50 titles to her name in every conceivable genre, from The Grass is Singing to science fiction. She was not a fussy stylist. In the clear-eyed, broad-ranging empathy of her fiction, her overriding concern was to get to the heart of a matter. A practical essayist and sensible thinker, she deplored political correctness, and other assaults on the language.

It’s the end of a culture we’re living through whether we like it or not

She had a reputation for being rather stern, but on the summer afternoon I met her she was wreathed in smiles. That squaw-like physiognomy of hers aged magnificently but there was a part of Lessing that has simply refused to grow old with it. I interviewed her in her home in West Hampstead, stretched over three storeys in a terrace on a hill. She lived alone. In the large L-shaped first-floor room where we talked there were books everywhere, including an art book open at a painting by Uccello. She made a habit of turning the page each day. “With any luck I’ll die here,” she said.

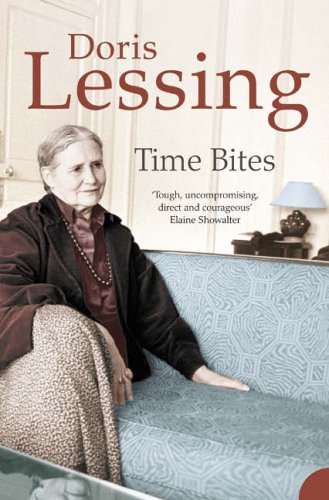

The pretext for our conversation was the publication of Time Bites, a collection of essays. A great palimpsest of Lessing's enthusiasms and bugbears, it turned out to be a wonderful springboard for covering a huge range of subjects from the politics of the sex toy to which male authors would have been good in bed. But we began, much to my surprise, by discussing the ethics of the penalty shoot-out - this was soon after an England international match David Beckham contrived to miss two spot kicks. DORIS LESSING: I don’t know why they don’t toss a coin. I hate it, I really do. And also it’s unfair. And after all that expertise. What about that one that David Beckham kicked up that lump of dead grass?

DORIS LESSING: I don’t know why they don’t toss a coin. I hate it, I really do. And also it’s unfair. And after all that expertise. What about that one that David Beckham kicked up that lump of dead grass?

JASPER REES: To misquote Oscar Wilde, to miss one penalty…

Well now, Victoria’s having another baby. Oh well. Do I care? No. It’s very interesting what you don’t care about. You know all these things. It’s bread and circuses. I’m sure that’s the wrong analogy. But people are going to watch Big Brother or whatever it was. I don’t understand why. I thought it was very boring. I know people who wouldn’t go out because they wanted to see it. I saw one of the first series. I thought, well… Then I saw a tiny bit of the last one and I thought that was unspeakably awful. It was so grubby, wasn’t it? Now which book are we talking about?

Time Bites.

Have you read any of it?

I’ve read all of it. But not much about cats.

You either like them or you don’t. I think partly they are so beautiful when they are beautiful, and they are so entertaining. I swear they’re psychic. They really do seem to know what you’re thinking.

Are they the only animal about which you could write?

No I love dogs. I wrote a story about dogs which appears in anthologies, and I’ve just written a book which is not out yet, which is a sequel to Mara and Dann where the major character is a dog because I miss them so terribly. I’m not going to have a dog in London, so I thought I’d write myself a dog. The trouble is that now I’ve finished I’m just as dogless as I was before.

Is this book of essays required writing, as Larkin called reviewing?

Well I have enjoyed some of it very very much. I’ve never written reviews for money. I only review books if I like them. I know that might make a very dull tone, but I prefer writing novels of course because I like telling stories. Writing prefaces has been great. These books that you’ve adored for years, suddenly they ask you to write about them. I am your original autodidact. Books have been my life, I was educated on them. And then suddenly in your old age you have these people asking you to write about books that you’ve been in love with for years. What a bonus that is.

Do you research much?

When Lawrence writes about sex, you suddenly realise he doesn’t really know very much about it

Not much research. My memory is not good, you know. At this very moment I’m doing one that really appeals to me, slowly. That is Lady Chatterley’s Lover for Penguin. What is interesting is if you’re interested in a subject things will come in from everywhere on that subject. My personal thesis is that that book has got a great deal to do with World War One. I haven’t read this anywhere else but naturally I’m convinced I’m right. So yesterday I hear William Golding’s Lord of the Flies discussed by a group of much younger people. Now he wrote that book because he was so appalled at the Second World War, what people were doing to each other, that it just broke his heart and he wrote Lord of the Flies. But this lot had never had their hearts broken by the Second World War and dismissed this as if it was of no importance, whereas it’s crucial. I think the same thing is true of Lawrence. First of all he was dying of TB. That is a book about cherishing the flesh. The whole of Europe was covered with putrefying corpses. So I’m thinking about it all the time with one part of my brain. And you put yourself into his state of mind, because he was a bit batty, wasn’t he? Never mind.

You are also quite harsh on him as a performer in the bedroom.

Have you actually read Lawrence? When he actually writes about sex, you suddenly realise he doesn’t really know very much about it, does he? All his setpieces about sex, they’re like the dreams of a schoolboy, really. And the idea that sex can’t be perfectly inspirational, spontaneous and sort of an act of God almost, he regards as quite disgusting. God knows what he’d think about vibrators. I can’t even bear to think. He’d die at the humiliation of it all.

It cuts out the need for the male.

Does it? I’ve never had a vibrator myself simply because I like men. But I know women who have vibrators and have everything and it doesn’t cut out men at all.

But that’s how he’d see it.

How did we get onto vibrators? Oh yes, Lawrence and sex. What about Tolstoy and sex? Have you ever read The Kreutzer Sonata? It’s a mad mad document. I don’t care what anybody says. If he hadn’t written that no one would be brooding about what he thought about sex. You don’t sit down and think, what was Tolstoy like in bed? Unless he drew your attention to it, which God knows he did.

Which male writer was good in bed?

Well you see it’s very hard to say, isn’t it? As they write. I haven’t really thought about that.

You’ve plainly thought about the ones who aren’t.

Well that’s only because they ask for it.

Talking of the sex lives of novelists, what did you think of the film Iris?

It made me so angry. You know I knew her. She would have thought that was such a betrayal. There’s no need to summon up her ghost. It was a terrible terrible thing to do, and what interested me was a good many of my sensitive literary friends couldn’t see anything wrong with it. As if she was a non-person. I was terribly shocked. Anybody’s Alzheimer’s could have done for that. Not Iris’s.

You make reference to the film of The Hours in this book.

You make reference to the film of The Hours in this book.

Oh that, God. Can you imagine Virginia Woolf as this exquisite girl with the beautiful clothes? If you care about Virginia Woolf, which I certainly do, I was angry again. But what can you do? The music was very good by my pal Philip Glass. When I wrote that piece I was on a platform with one of the experts on Virginia Woolf and I told him the following anecdote. We are now back in the Second World War and one of the RAF who became friends said he’d met Virginia Woolf. He’d gone into the press and who was serving, wrapping up books, but Virginia Woolf? I said, "What was she like, what was she like?" He described her as a benevolent haystack, very untidy, very wispy. And this person was so angry. I couldn’t understand why. He said, "That isn’t printed anywhere." She was large, benevolent, wispy and untidy. She was not a beautiful young woman with an exquisite coat.

Is it possible to make a film about a writer and be faithful to their spirit?

I don’t see the point of it really.

In a way it’s writ-large version of what we’re doing now, which is talking about you.

I know. They could always read the book and find out what I’m like.

You’ve had a tremendously dramatic life.

Yes I have.

Has anyone asked to make Doris: The Movie?

Yes several times, and I’ve always said no. I don’t see the point of it, apart from anything else a movie takes up an awful lot of time. It also involves all your nearest and dearest. No one ever seems to think about that. Like biographies. What about your friends and relations? It’s very hard, isn’t it.

Have you any control after you’re gone?

I don’t care what they do after I’ve gone. They can do what they like. I’m not one of those writers that sits worrying about posthumous fame. I’m always amazed that anyone cares. We won’t be here, after all, will we, to worry about it. So I don’t care what they do and what they write.

And the movie?

Don’t care. I’ve written a version of Martha Quest for television but no one ever made it. It took me a long time to see that I was a bit of... First, everything I lived through is gone. It’s completely dead, everything I was brought up with. And how extraordinary it was. The white minority, all that’s gone, and not only that but I was brought up in this ecological paradise, all gone. I’m sorry that no one’s ever made that because I think it would be good. But never mind. It doesn’t matter.

Would a film entitled Martha Quest be a stealth version of a biopic?

Well it’s almost true. A lot of it is true. People always say, "Why, here was this raw girl stuck in the middle of the veldt, where do you get all these bright ideas from?" Actually I was reading all the time. But no one ever took this seriously so I invented when I was doing Martha Quest, I put in Jewish mentors who came much later in my life. So when someone was going to make a film of it he was Jewish and he became extremely Jewish. He didn’t just become the Cohen boys of the station. I stopped it. I’m sorry now I invented the Cohen boys and didn’t stick to the truth. The characters are the same. The belligerent fighting character, and the relations with my mother are the same. But there are an awful lot of invented characters.

Was your mother a reader?

She was when she was younger. What they were reading because of the War, they subscribed to war book clubs. The house was full of memoirs of generals and soldiers coming out by every post. And they read something no one now remembers called Stephen King Hall’s Newsletter. I think that was weekly. That’s what they read then. But the classics which they’d have read were read by me and all the amazing children’s books. It’s taken me a long time to realise just what a feat that was. All these books came to this farm in the middle of the bush. And they were wonderful. I can’t think of any children’s books she didn’t get for me.

Have you been back to the farm?

Yes I have. It’s been squatted. It’s loaded with people and there’s very little water on that farm. It’s got an iffy bore-hole and a couple of iffy wells and in the wet season they fill up with water and then in the dry season they are just holes. These people are having to walk to fetch water from the rivers three or four miles away, which of course women are doing all over Africa. But it hurts you know, it really does. I went several times. But my parents moved to Salisbury during the Second World War. My father was extremely ill and it was a really terrible time, really awful.

What did your mother think of Martha Quest?

I don’t think she ever read it. She read The Grass Is Singing. From her point of view this was just such a terrible thing because at the time it came out it was quite revolutionary, believe it or not. And for her and her kind it was a blow in the solar plexus, how could I be such a traitor and all this. She really thought like this. So when she wanted to come to England and live with me she would have to swallow a very great deal of pride, which I didn’t see at the time. And also she was always hoping that she could reform my thinking and get me to see the virtues of the British Empire.

I don’t think she ever read it. She read The Grass Is Singing. From her point of view this was just such a terrible thing because at the time it came out it was quite revolutionary, believe it or not. And for her and her kind it was a blow in the solar plexus, how could I be such a traitor and all this. She really thought like this. So when she wanted to come to England and live with me she would have to swallow a very great deal of pride, which I didn’t see at the time. And also she was always hoping that she could reform my thinking and get me to see the virtues of the British Empire.

Even though it was falling apart.

They didn’t see that at all, even though India had gone before my father died. They really did think the British Empire was God’s gift to humanity.

When did your mother come?

It must have been about '52 or '3. That was absolutely terrible because all this time she’s been dreaming about going home to this life she’d left which was no longer here. Maybe it’s here now after all these years. She would be more likely to find it now than she did then after the war. She’d had a rather good girlhood. Very jolly, parties and picnics and sports and going to the show, and then supper at the Trocadero. And suddenly she’s landed back in post-war London with a daughter who’s freezing her out.

And an active communist.

That was already fading. It wasn’t the communism she minded. It was the blacks. That’s what she couldn’t bear. My God she’d be so delighted now to see what’s happened [in Zimbabwe]. All that lot there. She’d say, I told you so.

Your first novel cleansed her of the desire to read more.

No. If she read Martha Quest she never said so. It was actually a very cruel portrait of her. It didn’t stop her wanting to live with me. But then she was desperate. She wanted to live in England, the other England

did you feel half-foreign when you arrived in England?

I was brought up on English literature, that was my education, and my excessively British parents. But on the other hand you are never anything but a foreigner. But then look at London. You have to go outside London to meet the kind of people my parents were. They tolerated foreigners I would say. They weren’t anti-foreigner. On the contrary, it’s just that they were so British that it insulated them against understanding what the rest of the world was like.

Did you feel you were coming home?

Yeah I did. I would have left Southern Rhodesia when I was 19 if the war hadn’t started. And everyone got married so I got married. I would have left, and then I had to stick it out for another 10 years.

You were in your own mind a different kind of British from your parents.

I didn’t even think of it. I took it for granted. If you had a Southern Rhodesian passport you were British. And I married this German in the middle of the war which was not very nice for my parents, though I have to say they behaved decently. There was no such thing as anti-Hitler Germans, and that was true of a lot of the Brits. There were Germans. It must have been very hard for them.

You talk about this as it’s another life and yet it seems very immediate. It seems so long ago – “I married this German”.

We are going back how many years. What it is you are here now but at any time you can put yourself back into all that scene. It’s not that it’s somebody else. It’s just that you see it differently. I was such a fighting girl with my fists up all the time. All that left me long ago and I don’t know if it’s a good thing or a bad thing. It certainly gave you a lot of energy, I can tell you.

Overleaf: Lessing's reaction to winning the Nobel, and her views on the future of books and reading

Is this your greatest hits of non-fiction?

Is this your greatest hits of non-fiction?

No what happened was when I’d started writing these pieces for Hesperus and I’d written one after the other and I thought I’ve got all this stuff lying around this house, I’m always coming on it in drawers and heaps - why not collect it together? At any rate I can throw everything out. And then I got involved in it because I was quite interested to see about some things I’d written and forgotten about completely. This isn’t the collected works, you understand. I’m not tidy enough for that. It really is awful.

That’s the job of your literary executor to sort that out.

Good luck.

Is there a theme running through this book?

I don’t know if there is one, is there?

The fundamental importance of reading.

That’s true, particularly now when kids don’t read. I keep trying to persuade myself that it’s unimportant, the fact that this culture is coming to an end, or probably is. So what? But when I think of the sheer pleasure of it, that hurts too. When I meet some young people you can’t talk to them, they are so ignorant, and that’s because they haven’t read anything. What about this fairly common person who’s an absolute specialist in something difficult, I don’t know what, anything, computers, and they haven’t ever read anything. That’s all they know. Suddenly you find you can’t have a conversation with them except about what’s in the shops. That’s very painful, you know, when you think of particularly of the hunger for books in the Third World.

If there’s another theme, it is that everything you say seems so wonderfully sensible.

You mean I’m complacent.

No, but you can see what needs to be put right although you understand the impossibility of putting it right.

That’s such a tactful way of putting it. Well, maybe.

Why have people stopped reading?

Oh, because there are more interesting things to do, like television of course. It’s the end of a culture we’re living through whether we like it or not. I think what will happen to books is that they will continue to be read by a minority who will be passionate about them. But at one time the respect for books and reading was general. It’s not there now.

Are you not thrilled by Lynne Truss’s book about punctuation?

Wonderful. All that is true. There are people who care enormously, people in publishing battling against these empires, and all that is wonderful. I seem to have spent and all my friends have spent God knows how long lecturing about and trying to get kids to read, but the fact remains that there was a time when there was a general respect for literature and books and it’s not there now. It’s not literature and learning or education that’s not respected. It is a glamour – God help us – of being a writer. God knows where they get that from I think some of them genuinely do believe a writer’s life is all publishing parties and festivals.

Was it Roth who saw there were American writers who would saw off their left arm to undergo the experiences of the writers on the other side of the Iron Curtain?

And it’s true of South Africa as well for a while. Yeah I suppose they would. But I can’t see that Americans are short of subjects, can you? Philip Roth hasn’t done too badly.

Is your doom-laden prophecy of the end of a culture a function of your age?

It’s not all doom-laden.

The culture ending?

Maybe there’ll be a better one. When the print revolution went general that was the end of something. It was the end of a lot of the old culture. People lost their memories. At one point it was all in their heads. Now you have reference books and telephone books and God knows what. That was the end of the culture. But what’s new? There’s bound to be something. The human animal or the psyche is always coming up with something unexpected. I’m not saying it’s the end of books, I don’t think it is, they’re too convenient. But something else will happen? What will it be, I wonder. Perhaps they’ll go back to telling stories.

When you write non-fiction is it from a different part of your brain?

When you write non-fiction is it from a different part of your brain?

Yes it is. You are after all concerned that you are telling the truth. There’s a different kind of continuity. If you’re writing a story then that evolves, it has a life of its own, and I even dream parts of the story, which is very nice. But when you are writing a thinkpiece I am so forgetful and I sometimes make the most terrible mistakes, which they don’t catch.

Do you write on a computer?

No I haven’t got round to it yet but I shall have to. I will at some point or other. I write on an old-fashioned typewriter, which is pretty shameful. I take kids up to show them my typewriter and they don’t know what it is. A schoolteacher told me this story. She was appalled that none of the children knew anything about the past. So she devised the following lesson. There was a cupboard in the corner of her room, and she told the kids to go into the cupboard, imagine something from the past, and come out and tell everybody. And she said nobody went further back than the 1980s.

We live in a time when no one has to wonder what all the fuss was about.

To me one of the most astonishing things illustrating this is that girls, young women, have no idea what birth control has done for women. Until two generations ago most women spent their lives worrying about getting pregnant and they got pregnant and they had eight kids and they died in childbirth. The young women have got absolutely no idea. This seems to me so amazing that I can’t believe.

Would you have liked to have been a young woman in today’s social and sexual climate?

I have to say I didn’t notice that we were sexually so deprived. It’s the convention now to say it’s all the fault of whatisname saying sex started in 1963. What I do like is the fact that the young ones don’t know anything about war. I was brought up with First World War and the Second World War and there’s something about you lot which is much saner, you know. I maintain that we were all screwed up by war and we didn’t know it. The famous 1960s generation, all that lot had either been small children in the war with daddy away, mummy probably on munitions, air raids, all that, and then time passed and there was a certain frenetic quality about them. My analogy is a stream that runs clear that’s been turbulent. That’s what I like. I like meeting young people who haven’t ever been afraid.

It was well put by David Hare: the generation who grew up in the 1950s with parents who wanted a quiet life after the trauma of the war but as they hadn’t experienced the trauma to explain the craving for quiet they went nuts in the 1960s.

The change in the late 1950s. When I came in the early 1950s people talked about the war all the time. They were either soldiers coming back or they’d seen the concentration camps or they’d been bombed. And then there was a new generation in '56, '57, and they found the war very boring. And while they had been affected by the war they stopped talking about it. They didn’t want to know. While it was quite a shock it was the beginning of something else, of people not being traumatised. My parents were both traumatised by the First World War and all of that lot were. It always takes you a long time to see things. It took me a long time to see that this woman was traumatised by the war. You don’t listen when you’re a kid. Later you hear it. The carts and the lorries coming up with the wounded and stacking them in the corridors. What must that have been like, these people dying? It must have been absolutely terrible. And then the man was in love with drowned. So there we are. They had it bad.

They are a very hysterical nation. We never see it or say it

In a way you are berating yourself for having shown a lack of understanding? Or not having the equipment to understand.

I didn’t have the equipment. I was desperately sorry for my mother always. That I did have. It didn’t mean that I didn’t have to fight her, because she really would have swallowed me up. She was a swallower-upper, through no fault of her own. This woman should have been running chemical industries. She was extremely efficient. She had an invalided husband and two children who spent all of their time trying to get from under her. I mean what a nightmare. She had a terrible life. She was eating herself up with her own efficiency really. It was terrible. I am very very sorry for her. Which does not mean that I was wrong. I had to fight her. There is a kind of woman in our culture who is obsolete as far as I can see, and that is the one who has put all her life into looking after children and then they grow up and then they go crazy. All my women friends had mothers and we knew what was wrong with them and we were right: they needed jobs, instead of which they persecuted us, all the time. Nobody’s fault, as usual.

Have you inherited anything from her?

I’m very practical when I want to be, like her. I don’t think I’m as intolerant as she was, I hope. I’m a practical person. You might not think so. But I am. I can cope. I was never driven mad by war. I was never driven demented by that bloody war. They were both crazy. It took such a long time to see it.

Do you read your own reviews?

I read the ones in the newspapers I get. It would be a bit neurotic not to. It’s a much bigger subject than you think. It’s not just looking at reviews. It is the whole machinery. I’ve got a website which is run by a woman I know which I’m told is marvellous but it’s very easy to become captive to your own image. It’s much easier than you think. So I try to avoid all that. People who send these amazing essays written about your work, which I try not to read.

You are intolerant of the academic way of reading. There is great stuff in your essays on PC.

I hate that. It’s done so much damage.

I love it when you say students were reading The Good Terrorist, scouring it for evidence of wrong thinking. Would you much rather it weren’t taught at all?

I love it when you say students were reading The Good Terrorist, scouring it for evidence of wrong thinking. Would you much rather it weren’t taught at all?

That’s another thing. Now I look upon the universities as the equivalent of the monasteries in the Middle Ages. In some countries my books are known in the universities but people don’t have the money to buy them, so I can’t know that, can I?

All right, in America?

I don’t know. America is another thing. They just go in for extremes, don’t they, always, and I don’t know why that should be. They are a very hysterical nation. We never see it or say it. We don’t. Why don’t we see this? They are always off on some limb there, banging a drum about something.

Have you changed as a reader of your own stories?

It’s the same thing. You can put yourself back to the person you were when you wrote that story. A lot of books when you reread them, don’t they change for you completely? Twenty years pass and you reread something and you’re amazing at what you didn’t see.

Or that you liked it in the first place. I recently found I couldn’t stand Esther in Bleak House.

I don’t like his women very much. It’s not his strong point.

He probably wasn’t that good in bed?

Well I don’t know. How about Ellen Tiernan? She seemed to go for him. I’ve got a feeling he might have been. We’ll never know, will we? How about George Meredith? Now he really liked women. No one ever reads George Meredith. And he wrote some fantastic books. Henry James we know would have been useless. He’d have been delivering lectures. Funny, I’ve never even thought along these lines. I maintain Tolstoy was mad at the end. Anna Karenina is so full of understanding. It’s as if The Kreutzer Sonata was written by someone else. It’s a truly shocking book. The life he lived with his countess, the pair of them were round the bend, I wouldn’t be surprised.

Do you relish using words like "scumbag" of Lawrence?

There are quite a few adjectives used about him.

That’s a noun.

Sorry. It’s true. That’s terrible, isn’t it? I was thinking about the amazingly strong reactions to Lawrence which are still going on. Do you realise you are actually blushing? Very funny. Lawrence arouses such violent emotions that I find astonishing. When I was young everyone was madly in love with Lawrence.

We did say 'I love you', but not when we are off to the grocer’s

Do you relish the word, though? It must be from America.

I should imagine it must because most of the violent reactions come from America.

Do you rejoice in the fact that the language is changing?

Yes I do. I wish we didn’t always adopt America’s latest fashion but we do, and particularly I don’t forgive them for this awful business, I love you I love you I love you. We never used to do this. Now all the time. And now soaps. It’s terrible. It’s like saying goodbye or hello. It’s become absolutely meaningless. We have to find another word, or not say anything, which after all we got by quite nicely with for a time.

You’ve never been a very adjectival writer. Does that make the conversion across to writing essays easier?

You are writing from a different part of yourself. You are writing from your head somewhere, whereas when you are writing from a story it’s a much deeper level you’re writing from.

Do you like Lady Chatterley?

I like a lot of it. I think it’s a very flawed novel. I keep thinking of the excitement when I first read it. What I like Lawrence for is his capacity for immersing you in the experience. No one has ever written as vividly as he had. Scene after scene in that book I almost don’t care what he wanted to say. Like "The Fox", an extraordinary story. How many years since I first read that? When I reread that after many decades and it was as if I was still reading the first time his capacity for making things come to life. No one else has ever had it, I don’t think. It’s unique. I don’t know what we should value writers for. Certainly not for their blueprints. We don’t enjoy Jane Austen because she might have had views about Napoleon. Only her sister would know. We are always trying to make writers into something else. We don’t value them for what they actually offer. Why does Lawrence talk such rubbish about men and women, which he often did? Why not enjoy him for what he uniquely provided?

People are always turning you into a feminist.

Well I’ve had every conceivable label. I started off as a writer about the colour bar, and then I was a communist, then I was … now I’m beginning to forget. Then I was a feminist, then I was a mystic.

What are you now?

What I always was. Just the same.

Doris Lessing, née Tayler, born in Kermanshah, Iran (then Persia), 22 October 1919. Died in London, 17 November 2013

Doris Lessing hears she's won the Nobel Prize

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment