theartsdesk in Bordeaux: Bottoms up for Rameau | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Bordeaux: Bottoms up for Rameau

theartsdesk in Bordeaux: Bottoms up for Rameau

Daring production of an innovative opera-ballet in a perfect 18th-century theatre

Jean-Philippe Rameau, the most radical and inventive of French composers before Berlioz, died in Paris 250 years ago this September. 16 years later a gem among theatres opened its doors for the first time with a long evening’s entertainment including Racine’s Athalie, supported by an incidental score from the resident music master Franz Beck.

There I caught in full, startling production flight not the Rameau opera which most often turned up in the Grand-Théâtre de Bordeaux's early repertoire, Castor et Pollux, but what was originally called a "ballet heroïque", Les Indes galantes. You can hear it in concert, with most of the same singers and Christophe Rousset’s fizzing band named after a Rameau operatic subtitle, Les Talens Lyriques, at the Barbican this coming Thursday.

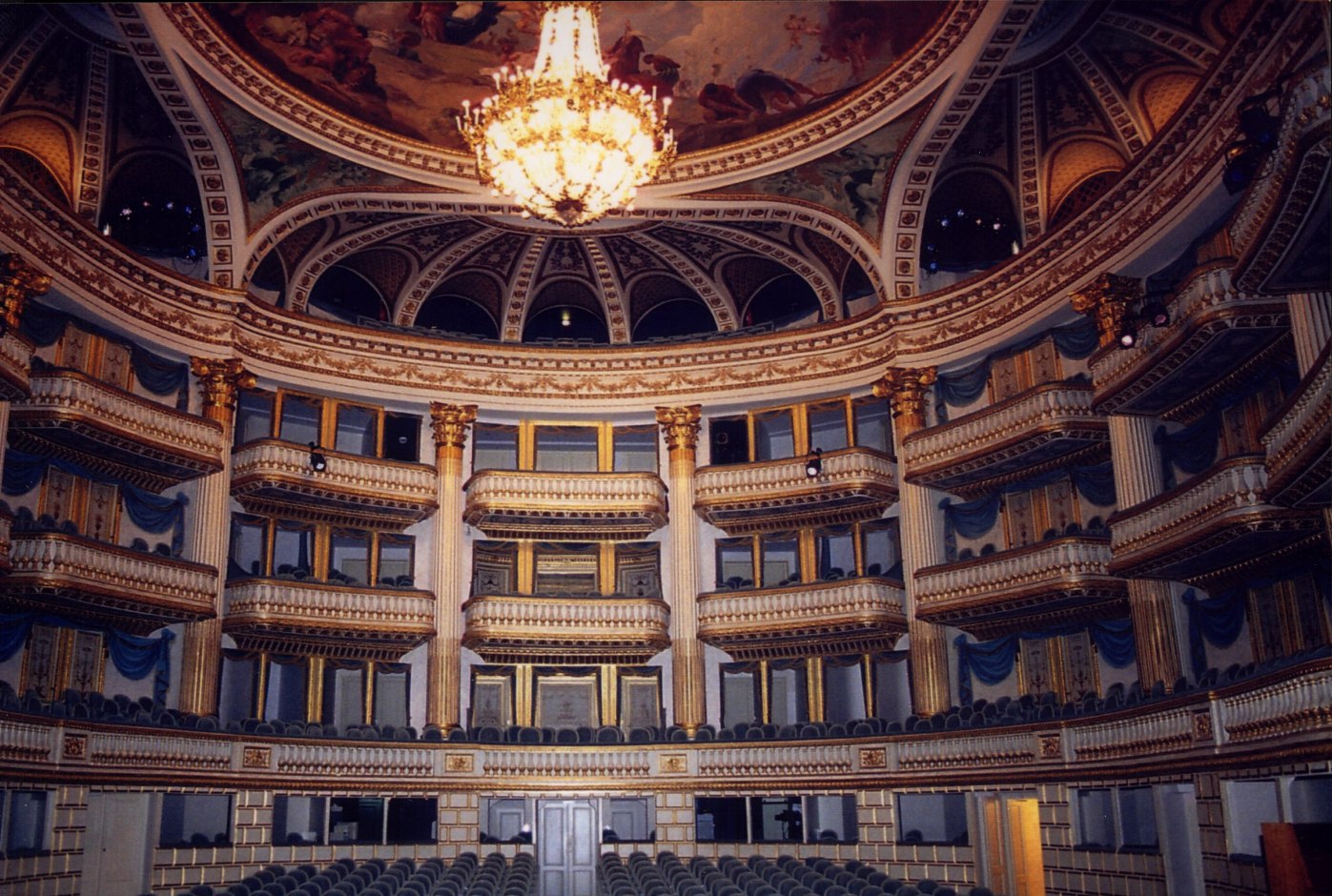

The Grand-Théâtre began life in 1773 with the express approval of the Emperor whose long reign had also welcomed Rameau’s lavishly staged court entertainments, Louis XV (he died after a long reign the following year). Unlike the old Paris Opéra which hosted so many of Rameau’s entertainments, but like the theatre in Versailles where I was lucky to catch Rousset's championship of Lully’s Bellérophon at the freezing end of 2010, it has survived miraculously intact, albeit with a 19th-century makeover and a more recent return to something like the original décor.

The Grand-Théâtre began life in 1773 with the express approval of the Emperor whose long reign had also welcomed Rameau’s lavishly staged court entertainments, Louis XV (he died after a long reign the following year). Unlike the old Paris Opéra which hosted so many of Rameau’s entertainments, but like the theatre in Versailles where I was lucky to catch Rousset's championship of Lully’s Bellérophon at the freezing end of 2010, it has survived miraculously intact, albeit with a 19th-century makeover and a more recent return to something like the original décor.

It remains perhaps the chief 18th-century glory of a dizzyingly beautiful city which achieved UNESCO World Heritage status in 2007, and it’s home to the vibrant Opéra National de Bordeaux, which welcomes productions as outlandishly inventive as the one I saw here last week, director-choreographer Laura Scozzi’s take on the exotica of Rameau’s picaresque travelogue. The Indes of the title are hardly "Indies" as we understand them; the name covers lands with which France then had major links - Turkey, Peru, Persia, north America.

If only the audience could see on Thursday what I saw two Fridays ago, not least the multiple Adams and Eves who gambol around Hebe in Prologue and Epilogue – quite the loveliest and most innocent naked choreography ever, surely. Stage nudity is rarely sexy, least of all when bits jiggle so, but Scozzi's prelapsarian dancers were sweeter than sweet.

If only the audience could see on Thursday what I saw two Fridays ago, not least the multiple Adams and Eves who gambol around Hebe in Prologue and Epilogue – quite the loveliest and most innocent naked choreography ever, surely. Stage nudity is rarely sexy, least of all when bits jiggle so, but Scozzi's prelapsarian dancers were sweeter than sweet.

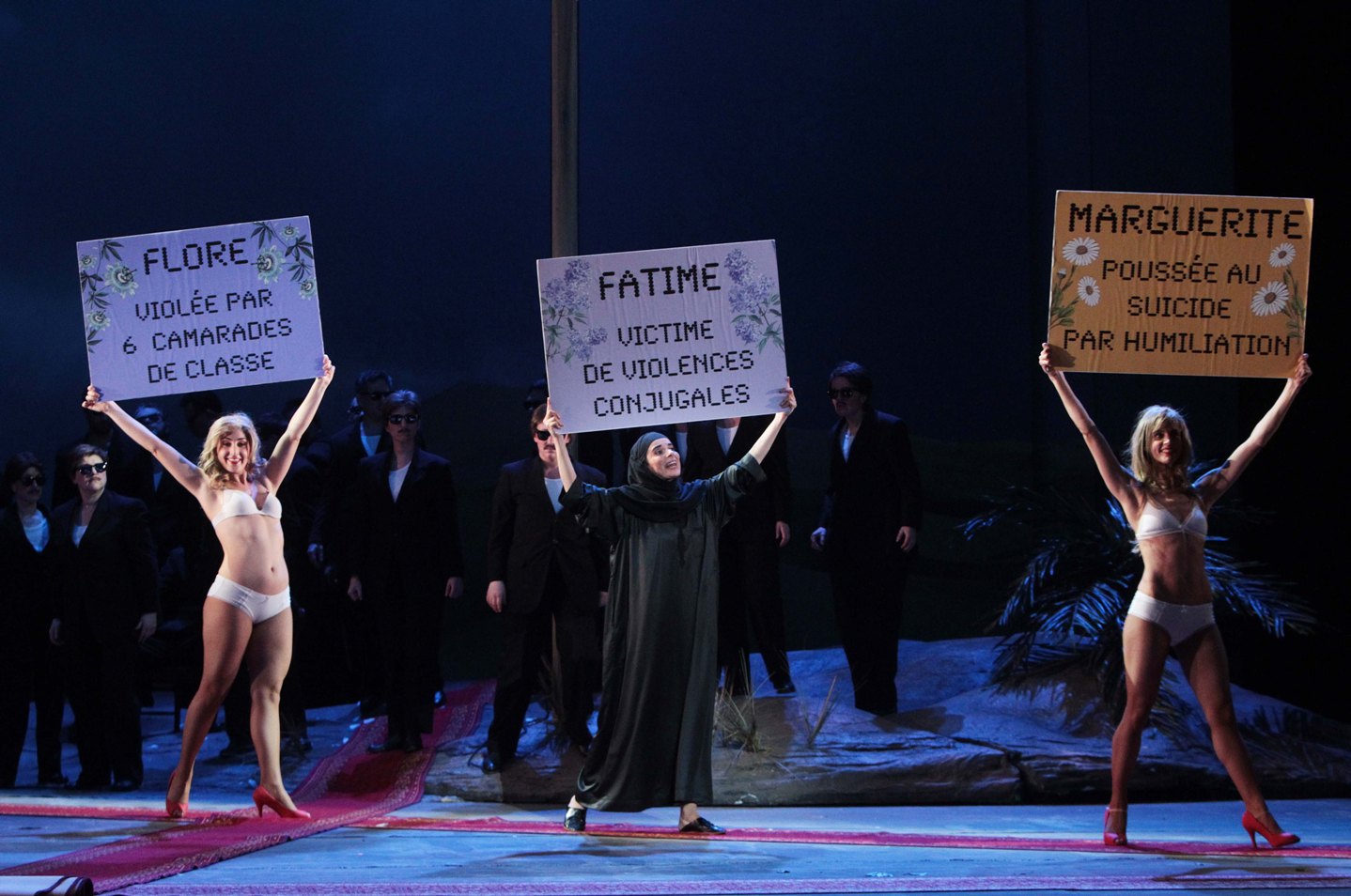

The audience will also miss a scene which I doubt would pass censorship in London. Scozzi has a threading message through all her Indes which ties in neatly enough with the original theme: the loss of innocence in the shape of sexual subjugation. Abducted Emilie, once her “Turc généreux” (Vittorio Prato pictured above with Judith van Wanroij) hands her over to her shipwrecked/hijacked lover Valère, decides she wants to stay with him in a Scozziesque twist; Phani is brutalised by a drug baron, not an Inca; and Fatime yearns for domestic slavery. This was edgy theatre: the Iranian men – which also means the women of the chorus in drag, just as the male dancers play the women – lord it over blond-wigged dollies in skimpy underwear as well as chadored ladies. The message of maltreatment is spelled out in a banner parade.

Laboured? Almost; and there’s often too much going on when solos are being sung, above all what will certainly be the hit vocal number at the Barbican when Carolyn Sampson sings it, the Italian aria for Fatime which Rousset has wisely drafted in to his performing version (Richard Strauss’s Countess quotes it as her Rameau favourite in Capriccio). But there's always light entertainment on hand from the three cupids, one of them a very agile fat lady. I feared at the start it would grate, but they managed to ring the changes enough to avoid monotony and repetition - always a risk in staging Rameau. And there's redemption to hand in the dignity of natural woman Zima and a final curtain which sees an old, pregnant Eve walking across the stage arm in arm with her Adam.

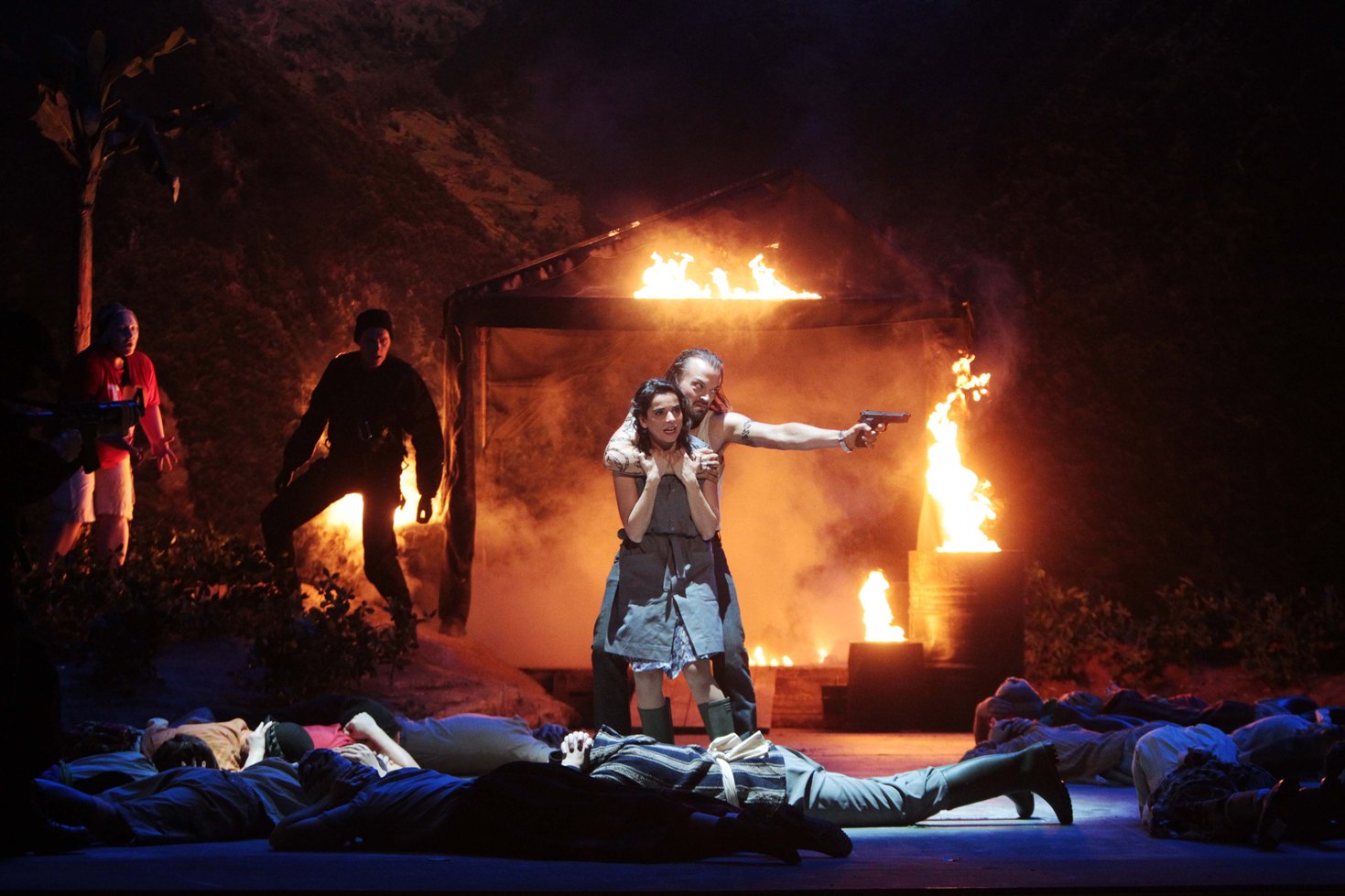

Vocally, Bordeaux’s line-up was a mix between early-music voices swallowing too many of their notes but certainly possessing the right agility – chiefly Amel Brahim-Djelloul, Sampson’s predecessor and tenor Anders J Dahlin – and more generous operatic voices, the stylish Judith van Wanroij and above all Nathan Berg (pictured with Brahim-Djelloul in the denouement), who gets the gravest, most spectacular music in the piece in villainous Huascar’s hymns to the sun, for which Rousset’s strings pull out their gravest stops, too.

Vocally, Bordeaux’s line-up was a mix between early-music voices swallowing too many of their notes but certainly possessing the right agility – chiefly Amel Brahim-Djelloul, Sampson’s predecessor and tenor Anders J Dahlin – and more generous operatic voices, the stylish Judith van Wanroij and above all Nathan Berg (pictured with Brahim-Djelloul in the denouement), who gets the gravest, most spectacular music in the piece in villainous Huascar’s hymns to the sun, for which Rousset’s strings pull out their gravest stops, too.

He likes his sun, does Rameau, and there have been plausible theses that like his librettist Louis Fuzelier as well as, later in the 18th century, Mozart and Schikaneder in The Magic Flute, he uses it as a Masonic symbol of enlightenment. Not that Huascar, who sings extensively about solar power at the heart of the Peru act, turns out to be at all enlightened, but the great choral hymn to the sun at the centre of perhaps the most consistent masterpiece before the swansong Les Boréades, Zoroastre, certainly is.

The beleaguered architect of the Grand-Théâtre, Victor Louis, and his patron the Maréchal-Duc de Richelieu were known Freemasons, and my guidebook proposes that they devised a symbolic journey from “the dim half-light bathing the [entrance] hall, accentuated by the relatively low coffered ceiling” (pictured above on the night of the performance) to “the dazzling light flooding the great staircase”, Louis’ neoclassical pièce de résistance with its splendid statues of comic muse Thalia and tragic muse Melpomene flanking the central door. Admittedly the below image catches it at night, without the natural light from the dome above; here the classical symmetry's the thing (staircase and auditorium images by Frédéric Desmesure; other opera house photos by the author).

The beleaguered architect of the Grand-Théâtre, Victor Louis, and his patron the Maréchal-Duc de Richelieu were known Freemasons, and my guidebook proposes that they devised a symbolic journey from “the dim half-light bathing the [entrance] hall, accentuated by the relatively low coffered ceiling” (pictured above on the night of the performance) to “the dazzling light flooding the great staircase”, Louis’ neoclassical pièce de résistance with its splendid statues of comic muse Thalia and tragic muse Melpomene flanking the central door. Admittedly the below image catches it at night, without the natural light from the dome above; here the classical symmetry's the thing (staircase and auditorium images by Frédéric Desmesure; other opera house photos by the author).

Even in the most splendid theatres I’ve never seen anything as theatrical or magnificent as that. Charles Garnier took it into account, too, for the grand staircase of his 19th-century Paris Opéra. The Bordeaux auditorium is more what you might expect, its boxes decked out in blue, white and gold beneath a ceiling repainted in 1917 by Maurice Roganeau on the design of Jean-Baptiste Robin’s 18th-century original (the Art Nouveau chandelier is from 1917, too).

The seating is for 1,114, rather less than the 1,700 of 1780, but a reminder that “authentic” voices couldn’t have been that small back in the time of Rameau and Handel; some of the ones we heard simply didn’t fill the space. Let's not forget that Knappertsbusch conducted Wagner's Ring here with a slightly reduced orchestra in the pit.

The seating is for 1,114, rather less than the 1,700 of 1780, but a reminder that “authentic” voices couldn’t have been that small back in the time of Rameau and Handel; some of the ones we heard simply didn’t fill the space. Let's not forget that Knappertsbusch conducted Wagner's Ring here with a slightly reduced orchestra in the pit.

And so from the Masonic mysteries of the interior to the richly colonnaded exterior, its honey-coloured locally quarried limestone glowing, like most buildings in Lyons’ central grid-plan and riverside quais, in a warm late February sun.

Nine muses and three goddesses look down. From the Place de la Comédie you can strike off south into the handsome streets of shops and fine restaurants, buzzing in a good way on a Saturday night, towards the Gothic cathedral; head east towards the River Garonne and the quayside palaces; head west towards a zone of luxury around the apartment where Goya died and the library where an annotated edition of one-time mayor Montaigne’s Essays is lodged, and beyond that the Romanesque and Gothic glories of St-Seurin with the nearby early Christian necropolis; or head north towards the Botanic Gardens.

Nine muses and three goddesses look down. From the Place de la Comédie you can strike off south into the handsome streets of shops and fine restaurants, buzzing in a good way on a Saturday night, towards the Gothic cathedral; head east towards the River Garonne and the quayside palaces; head west towards a zone of luxury around the apartment where Goya died and the library where an annotated edition of one-time mayor Montaigne’s Essays is lodged, and beyond that the Romanesque and Gothic glories of St-Seurin with the nearby early Christian necropolis; or head north towards the Botanic Gardens.

Which last, along with the museums, I didn’t have time to do, and if I sound like a spouting mouthpiece for Bordeaux’s tourist information office, it’s only because I so fell in love with the city that I spent an extra night there instead of catching the intended train back to Paris on the day following the performance, and intend to return for longer. As for Rameau, I've been head over heels in love since the Glyndebourne Hippolyte et Aricie. Let's hope there's something in store when the 2014-15 season gets under way, for the London opera houses haven't done too well so far.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

The Makropulos Case, Royal Opera - pointless feminist complications

Katie Mitchell sucks the strangeness from Janáček’s clash of legalese and eternal life

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Add comment