Horst: Photographer of Style, Victoria & Albert Museum | reviews, news & interviews

Horst: Photographer of Style, Victoria & Albert Museum

Horst: Photographer of Style, Victoria & Albert Museum

The man who turned fashion photography into art

If events in the Middle East, the prospect of the school run or the onset of autumn are conspiring to lower your spirits, then escape to the V&A and immerse yourself in the dreamy elegance of Horst P. Horst’s magical fashion photographs spanning a career that lasted 60 years.

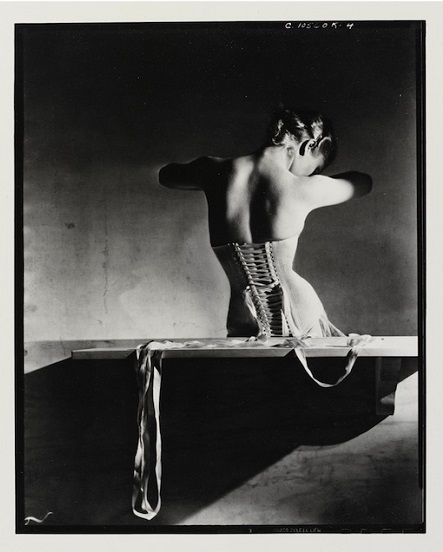

One of his most famous pictures (pictured below right: Mainbocher corset © Condé Nast/ Horst Estate) was taken in 1939, just before the outbreak of the Second World War. It's of a woman in a corset – not a promising subject – yet from this banal starting point Horst creates something supremely memorable. The model, Madame Bernon stands with her back to us in a bare space, leaning against a shelf. That’s all there is to it, yet this simple composition is drenched in poetry.

Every detail counts. The satin Mainbocher corset encasing the model is partially undone, leaving the ribbons to trail over the shelf and dangle enticingly in front of us. If you grabbed them, you could pull her in like a fish on a line; with her beautifully sinuous body, Bernon is like a free spirit, momentarily trapped.

Every detail counts. The satin Mainbocher corset encasing the model is partially undone, leaving the ribbons to trail over the shelf and dangle enticingly in front of us. If you grabbed them, you could pull her in like a fish on a line; with her beautifully sinuous body, Bernon is like a free spirit, momentarily trapped.

The shelf and wall beneath it are painted to resemble marble, in watery patterns reminiscent of surf gliding over wet sand. Thoughts of the sea are further evoked by the model’s pose; with her back emerging from the corset, she is like Venus rising from a shell, and with her head resting on her arms she seems lost in asleep.

The scenario would be too artificial if it weren’t for the lighting, which creates an atmosphere that is part sensuous, part melancholy, and wholly surreal. Horst, who would often spend two days arranging the lights for a shoot, later recalled that for this shot the lighting was so complex that he could never replicate it. It is also too complicated to describe; suffice it to say that it ranges from the clear light of reason to the velvet darkness of dreams and the night sky.

It was the last photo he took for French Vogue before leaving Paris for Le Havre later that day, to catch the boat for America. He described the picture as “the essence of that moment. While I was taking it”, he recalled, “I was thinking of all that I was leaving behind.” On the one hand it is just a fashion shot of a corset, a garment that traps women into enduring discomfort to achieve a wasp waist; but on the other hand, it's not too far-fetched to describe the image as emblematic of the moment when Europe was sleepwalking towards a hideous war.

It was the last photo he took for French Vogue before leaving Paris for Le Havre later that day, to catch the boat for America. He described the picture as “the essence of that moment. While I was taking it”, he recalled, “I was thinking of all that I was leaving behind.” On the one hand it is just a fashion shot of a corset, a garment that traps women into enduring discomfort to achieve a wasp waist; but on the other hand, it's not too far-fetched to describe the image as emblematic of the moment when Europe was sleepwalking towards a hideous war.

Horst’s acute visual sensibility allowed him to create images that, no matter how apparently trivial, were somehow able to capture the zeitgeist and reflect broader and more profound issues. Before moving to Paris, he had studied carpentry and design in Hamburg under the architect Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, the art school famous for promoting clear, uncluttered and intelligent design.

On his arrival in Paris in 1930, he was lucky enough to meet George Hoyningen-Huene, star photographer at French Vogue, who became his lover and mentor, introduced him to the Condé Nast studios and taught him how to use a large-format camera. Within a year Horst was also taking photographs for the magazine.

His previous training gave him the skills to construct inventive studio sets that transformed his fashion shoots into witty visual theatre. For a series taken in 1938, for instance, he placed a simple plinth and circle of wood in front of a plain backdrop. Clever lighting emphasised the abstract geometry of the composition.

His previous training gave him the skills to construct inventive studio sets that transformed his fashion shoots into witty visual theatre. For a series taken in 1938, for instance, he placed a simple plinth and circle of wood in front of a plain backdrop. Clever lighting emphasised the abstract geometry of the composition.

The fun began with placing the model. Wearing a nifty Schiaparelli hat, the disembodied head of Andrée Lorain appears to rest on the plinth beside her elegantly gloved hand, as though it was an element in a still life. The corner dividing the dark and light side of the plinth lines up with her perfect nose to lead your eye down to the wooden circle, now complete with a nipple-like object that transforms it into a large breast.

Horst was at his best creating magical effects with the simplest of means – the simpler the better. Wearing a black suit with white, “canoe paddle” sleeves, Lyla Zelensky rests her hip against a balustrade. The

contrasts between the slender curves of her body and the rectangular architecture, and the black and white fabrics produce exquisite visual poetry. But a memo from the editor expresses frustration with such arty lighting and imagery. “We have simply got to overcome the desire on the part of the photographers”, it reads, “to shroud everything in deepest mystery."

When Horst collaborated with artists such as Salvador Dali (pictured above left: Salvador Dali's costumes for Leonid Massine's ballet Bacchanale, 1939) and designers like Emilio Terry, the effect was to over-egg the pudding. Their input was superfluous; he didn’t need anyone to show him how to juxtapose a model’s hands and feet with plaster casts to produce a comical cluster that addresses the desire for perfection, or (when he was 81) to frame a woman’s naked bottom in a circle of frothy tulle in a delicious fusion of sexiness and innocence (pictured above right: Round The Clock, New York 1987).

When Horst collaborated with artists such as Salvador Dali (pictured above left: Salvador Dali's costumes for Leonid Massine's ballet Bacchanale, 1939) and designers like Emilio Terry, the effect was to over-egg the pudding. Their input was superfluous; he didn’t need anyone to show him how to juxtapose a model’s hands and feet with plaster casts to produce a comical cluster that addresses the desire for perfection, or (when he was 81) to frame a woman’s naked bottom in a circle of frothy tulle in a delicious fusion of sexiness and innocence (pictured above right: Round The Clock, New York 1987).

The same clarity of thought produced seminal portraits of the designer Coco Chanel, seen in 1937 nestling in the curve of a Louis XVI chaise, and actor Marlene Dietrich photographed in New York in 1942. She leans on the arms of a Louis XVI giltwood chair, her face bathed in soft light as she gazes dreamily into space.

But the New York editors wanted none of Horst’s moody lighting and monochrome mysteries. They were into wholesomeness, health and cheery colours. Included in this splendid retrospective are 94 of the covers he produced for American Vogue; they reveal that he still managed to pull the occasional rabbit out of the hat – as in the “Summer Fashions” cover for May 15th 1941 (pictured below). Wearing a white bathing suit and cap, the model lies on a white backdrop. On her toes she balances a big red beach ball which becomes the "O" in Vogue, while she holds the “V” in her left hand.

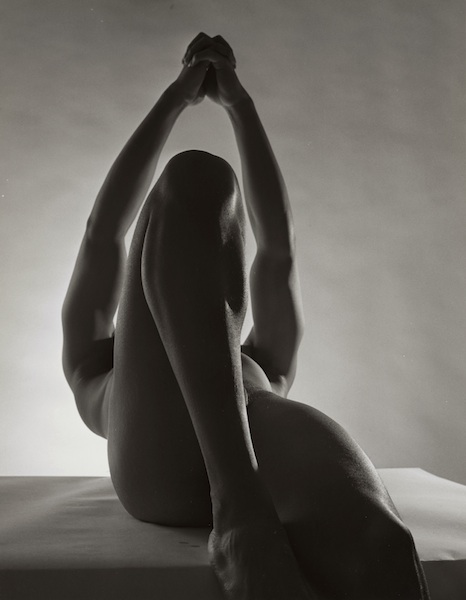

Images like this may be clever and stylish but the mystique has gone and, bored and frustrated, Horst began taking photographs on the side. In New York’s Botanical Gardens he shot close-ups of plants that celebrate the geometry of leaves and stems; a few years later in the 1950s, he dramatised the anonymous male body in a series of nudes approached with a similar mix of detachment and awe (pictured above left: Male Nude 1952).

When Diana Vreeland became editor in 1962, she commissioned Horst and his partner, Valentine Lawford, to produce features on the homes and gardens of the wealthy elite, including Karl Lagerfeld, Yves Saint Laurent and the Rothschilds. Horst’s own estate on Long Island, which he designed and nurtured with the same attention to detail lavished on his photographs, was also featured, thus completing the virtuous circle between his art and his life.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment