So many words have been expended on Egon Schiele, that it’s almost impossible to imagine what more can be added for such a relatively small and narrow, albeit intense, body of work. His was an early blossoming talent, and in his short life – he was 28 when he succumbed to Spanish flu, dying three days after his pregnant wife, in 1918 – he produced works preoccupied by sex and decay, riven by anxiety and fear, often marked by a tone of aggressive swagger. The work appears not only to embody the spirit of Vienna in the age of Freud, but also to betray his youth. Not for nothing has Schiele’s brutally frank and nervy eroticism been taken for the sex-obsessed, highly wrought angst of youth. And not for nothing has his best-known work spoken most directly to the teenager.

But one certainly can’t dismiss him on that basis, for Schiele’s talent as a draughtsman is impressive and there is an astonishing force and vitality in his thickly scored, tightly sprung lines. This means his work continues to exert its emotional, disquieting power, whatever your age, and, one might venture, whatever the epoch. This despite the fact that in the UK there is little opportunity to see his work in the flesh – no public gallery owns a Schiele.

So those who were lucky enough to catch the Schiele exhibition at the commercial Richard Nagy gallery in Mayfair three years ago might still have been taken by surprise at just how seductive and potent his works on paper are, their effects heightened by the close hang in the close, narrow space of the drawing-room-like gallery. With 50 delicate drawings and watercolours crammed onto the walls, many of course explicit and highly erotic, a heady, intoxicating atmosphere prevailed. You could almost imagine the fetid air of a Viennese brothel, or the artist’s studio, where Schiele was likely to have asked working girls to model for him.

It’s not quite the same as seeing a display in a carefully spaced museum hang, which is what you get at the Courtauld Gallery. Here there are a smaller number of works on display, some on loan from that gallery, while many are from the Leopold Museum in Vienna, which houses the largest collection of Schieles in the world. And like the Richard Nagy display, we’re again taken from 1910 to the year of his death.

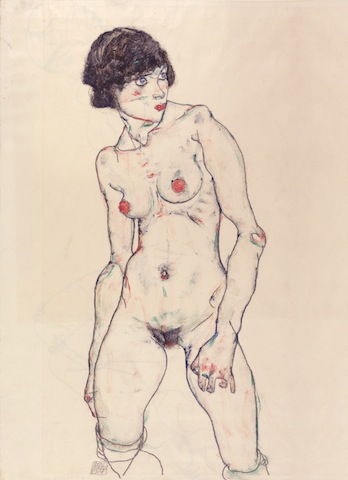

The early works are the most emotionally wrought. In The Sick Child, 1910, a young girl, her face a skull-like mask, lies with her hands raised to her mouth in anguish, their bold outline forming a suggestion of a slashed mouth. Her body is taut as if rigor mortis has already set in, while the area around her pink pubic mound and abdomen is painted with a white wash, as if – although quite stricken and possibly near death – her sex is emitting radial energy. The view of her naked body is a bird’s-eye view, though it is she who appears to be floating in space. (Pictured left: 'Standing Nude with Stockings', 1914; Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremburg)

The early works are the most emotionally wrought. In The Sick Child, 1910, a young girl, her face a skull-like mask, lies with her hands raised to her mouth in anguish, their bold outline forming a suggestion of a slashed mouth. Her body is taut as if rigor mortis has already set in, while the area around her pink pubic mound and abdomen is painted with a white wash, as if – although quite stricken and possibly near death – her sex is emitting radial energy. The view of her naked body is a bird’s-eye view, though it is she who appears to be floating in space. (Pictured left: 'Standing Nude with Stockings', 1914; Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremburg)

That same year he painted Seated Nude Girl, with Pigtails: a girl with a pallid rag-doll face framed by ropes of raven hair. Her long prominent fingers are blackened and she wears black stockings. This skinny, heavily made-up vamp looks about 12, with the model possibly being a young prostitute. She's both seductive and desperately fragile. Two years later, Schiele was arrested for “seducing” and abducting a girl below the age of consent. Charges were eventually dropped, though he was found guilty of exhibiting erotic drawings in a place accessible to children (children would apparently hang around his studio, in a suburb some distance from Vienna). He spent a total of 24 days in prison.

A genuine sense of transgression continues to haunt these works – perhaps more so today than ever. And it haunts particularly those works featuring his younger sister, Gertrude, who, in various semi-clothed poses, is caught in mid-theatrical gesture, such as we see in Sneering Woman. But it’s his self-portraits that appear especially fraught. Here he’s concerned with capturing his image in exaggerated postures – like the contorted frames of 19th-century hysteria patients, though he was possibly more influenced by a friend who had studied mime: we see prominent hands with long bony fingers splayed, while the jutting angularity of limbs and joints is also dramatically exaggerated. In Male Lower Torso, 1910, his flesh is especially bruised and putrid.

In later work, including his depictions of lesbian couples embracing, such as Friends, 1914, and Two Girls Embracing (Two Friends), 1915 (pictured right; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest), there’s an almost-tenderness – almost, but not quite, for these portrayals still retain a strangeness, a jarring confrontation with the viewer, and a sense of cold detachment in the lovers’ embrace. This tends to set them apart from Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings on the same, Sapphic theme. We find little sense of what we might call deep empathy here – the figures are too aestheticised, almost doll-like. Instead we are seduced, beguiled and bewitched.

In later work, including his depictions of lesbian couples embracing, such as Friends, 1914, and Two Girls Embracing (Two Friends), 1915 (pictured right; Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest), there’s an almost-tenderness – almost, but not quite, for these portrayals still retain a strangeness, a jarring confrontation with the viewer, and a sense of cold detachment in the lovers’ embrace. This tends to set them apart from Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings on the same, Sapphic theme. We find little sense of what we might call deep empathy here – the figures are too aestheticised, almost doll-like. Instead we are seduced, beguiled and bewitched.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment