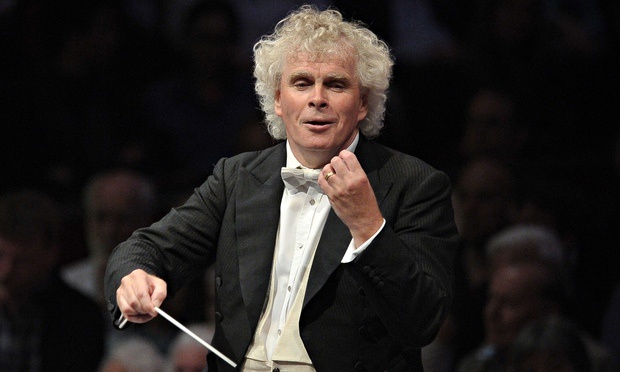

Sir Simon Rattle wants you to hear Das Paradies und die Peri. He is convinced that Schumann’s oratorio is one of the great undiscovered masterpieces of the Romantic era. To that end, he has led performances with the Berlin Philharmonic and an all-star cast, and has now brought that cast to London to convert the Brits.

He’s right. It is magnificent, and last night it received as good a performance as could be imagined. Every strength of Schumann’s art is showcased. The solo vocal writing is emotive and imaginative. The chorus is used prominently, and to excellent effect. The orchestration, true to Schumann’s approach, is skilful without being ostentatious. And, unlike so many other opera/cantata/oratorio hybrids of the era, it holds together well, with a clear structure, but enough harmonic and textural surprises to prevent it from ever seeming formulaic. The one major weakness is the libretto, an Orientalist confection based on Persian mythology. It is of little consequence or interest, and the music can be appreciated without too much concern about the narrative, slender as it is.

Among an impressively strong cast, the standout performance came from Sally Matthews (pictured right by Johan Persson) as the eponymous Peri, the spirit whose heavenly transcendence is the subject of the plot. Her delivery is powerful and clear, her tone rich and complex. Even in this quite staid oratorio context, this was a performance of operatic drama and engagement. Mark Padmore’s narrator stood back a little by comparison, but his too was an impressive reading, somewhere between Bach’s Evangelist and Schumann’s Dichter, never dominating but always engaging. Among the other soloists, Kate Royal struggled to match Matthews, in part because her tone was more fragile, but also her music was less interesting. She and Bernarda Fink, Andrew Staples and Florian Boesch each have an aria and combine for various ensembles, all to good effect.

Among an impressively strong cast, the standout performance came from Sally Matthews (pictured right by Johan Persson) as the eponymous Peri, the spirit whose heavenly transcendence is the subject of the plot. Her delivery is powerful and clear, her tone rich and complex. Even in this quite staid oratorio context, this was a performance of operatic drama and engagement. Mark Padmore’s narrator stood back a little by comparison, but his too was an impressive reading, somewhere between Bach’s Evangelist and Schumann’s Dichter, never dominating but always engaging. Among the other soloists, Kate Royal struggled to match Matthews, in part because her tone was more fragile, but also her music was less interesting. She and Bernarda Fink, Andrew Staples and Florian Boesch each have an aria and combine for various ensembles, all to good effect.

The choral writing is perhaps the most complex and sophisticated aspect of the work, with adventurous harmonies and unusual tessitura. The London Symphony Chorus gave a masterful performance. The more euphonious music, like the chorus that ends the second part, was particularly satisfying, but the greater skill was shown in the more intricate music, the polyphonic entries with which the chorus first enters, and the subtle accompaniments later on beneath Matthews’s fioriture.

Singing more than playing is the order of the day here, so the LSO was wise to field a relatively small ensemble, which balanced well and offered an accompaniment of classical elegance, only occasionally rising to more emphatic drama. Particularly impressive were the horn and trombone sections, each given a few short moments to shine, and both doing so spectacularly.

Singing more than playing is the order of the day here, so the LSO was wise to field a relatively small ensemble, which balanced well and offered an accompaniment of classical elegance, only occasionally rising to more emphatic drama. Particularly impressive were the horn and trombone sections, each given a few short moments to shine, and both doing so spectacularly.

But best of all was Rattle himself (pictured above by Chris Christodoulou). His passion for this piece was obvious from his every gesture, and for much of the work he could be seen silently mouthing the words along with the singers. Technically, his conducting was flawless, and his ability to negotiate Schumann’s often abrupt transitions gave the piece a sense of flow it may otherwise have lacked. His communication with the musicians is direct and powerful, the result more of a shared passion than of any histrionics at the podium. The London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus perform well for many different conductors, but never better than they do for him.

Add comment