Gods and Monsters, Southwark Playhouse | reviews, news & interviews

Gods and Monsters, Southwark Playhouse

Gods and Monsters, Southwark Playhouse

New play about the last days of 1930s Hollywood director James Whale

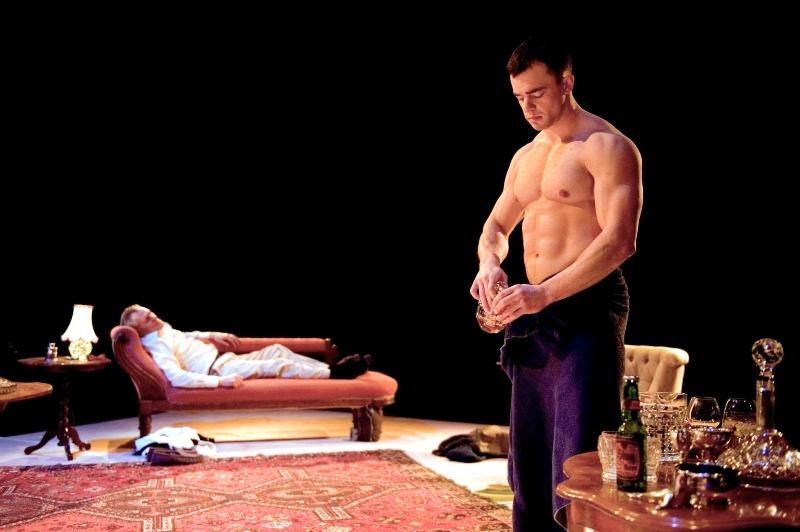

There is indeed something of Frankenstein’s monster about the handsome young gardener, with his flat-top haircut and gym-bulked torso, who has come to mow James Whale’s lawn.

The material comes from a speculative novel by Christopher Bram, which in turn inspired a 1998 film, with Ian McKellen Oscar-nominated as Whale – a pointed piece of casting given Whale’s sexuality: he was openly gay in an era when Hollywood barely had a name for such a thing. Labey’s play differs from the film in several respects, not least its refusal to present the developing relationship between the failing older man and the buff young groundsman as a romance. This James Whale (a convincingly tetchy and self-pitying Ian Gelder) has long since abandoned hope of consensual fumbling, let alone love.

We first meet him in 1957 as he is importuned by an over-eager film student (a standout debut from Joey Phillips, pictured right with Gelder) wanting to interview him at his home. This expository Q&A is just starting to feel clunky when Whale suddenly demands that the boy remove an item of clothing in payment for each answer. (“I do hope you’re wearing a vest today or we’ll break the bank very soon”.) The excitement of the debagging prompts in the old man what stroke doctors call an ischaemic incident: lights flash, white noise crackles, and Whale is transported to a memory of his first sexual encounter, at an evening school art class in Dudley, the West Midlands, pre-First World War. Such flashbacks, and there are many, are cleverly achieved on Southwark’s three-sided playing space, lit by Mike Robertson. We’re never in doubt what’s going on or who’s who (the accents are a reliable guide), at least not until the second half, when Labey (directing his own play) bizarrely takes it into his head to switch the casting of the younger Whale from Phillips to Will Rastall, who had previously played the friend or lover.

We first meet him in 1957 as he is importuned by an over-eager film student (a standout debut from Joey Phillips, pictured right with Gelder) wanting to interview him at his home. This expository Q&A is just starting to feel clunky when Whale suddenly demands that the boy remove an item of clothing in payment for each answer. (“I do hope you’re wearing a vest today or we’ll break the bank very soon”.) The excitement of the debagging prompts in the old man what stroke doctors call an ischaemic incident: lights flash, white noise crackles, and Whale is transported to a memory of his first sexual encounter, at an evening school art class in Dudley, the West Midlands, pre-First World War. Such flashbacks, and there are many, are cleverly achieved on Southwark’s three-sided playing space, lit by Mike Robertson. We’re never in doubt what’s going on or who’s who (the accents are a reliable guide), at least not until the second half, when Labey (directing his own play) bizarrely takes it into his head to switch the casting of the younger Whale from Phillips to Will Rastall, who had previously played the friend or lover.

Meanwhile, back in 1957 (though you sometimes doubt the dialogue’s authenticity – did folks back then say ‘I couldn’t be arsed’?), Gelder's Whale (pictured left) has persuaded the beefcake gardener, Clayton Boone (Will Austin, another newcomer), to pose for his life-drawing sessions. Boone, slow on the uptake, doesn’t clock Whale’s game, and the strip-tease of repeated sittings and Whale's wheedling for him to bare more flesh make these scenes painfully slow. The female perspective is briskly presented by the Spanish housekeeper, Maria (Lachele Carl), whose genuine kindness to the old man is clear, despite her purse-lipped disapproval of his lifestyle.

Meanwhile, back in 1957 (though you sometimes doubt the dialogue’s authenticity – did folks back then say ‘I couldn’t be arsed’?), Gelder's Whale (pictured left) has persuaded the beefcake gardener, Clayton Boone (Will Austin, another newcomer), to pose for his life-drawing sessions. Boone, slow on the uptake, doesn’t clock Whale’s game, and the strip-tease of repeated sittings and Whale's wheedling for him to bare more flesh make these scenes painfully slow. The female perspective is briskly presented by the Spanish housekeeper, Maria (Lachele Carl), whose genuine kindness to the old man is clear, despite her purse-lipped disapproval of his lifestyle.

You emerge from Gods and Monsters with a fair biographical knowledge of James Whale – learning that he was responsible for the long-delayed staging of that First World War gem, Journey’s End, at once endeared him to me – but not much about a gay director’s life during Hollywood’s Golden Era, nor the depressing after-effects of stroke. Jason Denvir’s set design, of walls and floors painted pale and veiny like the surface of a brain, suggest a textual intention that petered out somewhere along the line. At one point, Whale describes the moment he created the iconic look of Frankenstein’s monster in 1933: “a flat-topped head, like a tin of beef”. The idea that we might open the lid, as it were, and peer into the tangle of memories, desires and sensitivities contained within, is appealing. It’s what this play half-achieves.

rating

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Refuse / Terry's / Sugar

A Ukrainian bin man, an unseen used car dealer and every daddy's dream twink in three contrasting Fringe shows

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Faustus in Africa!, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - deeply flawed

Bringing the Faust legend to comment on colonialism produces bewildering results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Imprints / Courier

A slippery show about memory and a rug-pulling Deliveroo comedy in the latest from the Edinburgh Fringe

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Ode Islands / Delusions and Grandeur / Shame Show

Experimental digital performance art, classical insights and gay shame in three strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Ordinary Decent Criminal / Insiders

Two dramas on prison life offer contrasting perspectives but a similar sense of compassion

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: Kinder / Shunga Alert / Clean Your Plate!

From drag to Japanese erotica via a French cookery show, three of the Fringe's more unusual offerings

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, RSC, Stratford review - not quite the intended gateway drug to Shakespeare

Shakespeare trying out lots of ideas that were to bear fruit in the future

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Horse of Jenin / Nowhere

Two powerful shows consider the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, with mixed results

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Edinburgh Fringe 2025 reviews: The Fit Prince / Undersigned

A joyful gay romance and an intimate one-to-one encounter in two strong Fringe shows

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Tom at the Farm, Edinburgh Fringe 2025 review - desire and disgust

A visually stunning stage re-adaptation of a recent gay classic plunges the audience into blood and earth

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Works and Days, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - jaw-dropping theatrical ambition

Nothing less than the history of human civilisation is the theme of FC Bergman's visually stunning show

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Every Brilliant Thing, @sohoplace review - return of the comedy about suicide that lifts the spirits

Lenny Henry is the ideal ringmaster for this exercise in audience participation

Add comment