Altman | reviews, news & interviews

Altman

Altman

A genial but scarcely probing documentary about the great director

Ron Mann’s laid-back documentary about the career vicissitudes and family life of Robert Altman (1925-2006) takes its cue from the tone of the director’s films. It was Altman’s habit to observe his character’s crises, collapses, and deaths with the same evenness and lack of melodrama with which he observed their humdrum moments.

Although there’s a powerful current of liberal anger in Altman’s work, at the core of it there’s an acceptance of the reality of Social Darwinism, manifested particularly in the American Way. Optimism goes hand in hand with opportunism, as demonstrated by a scene that Mann quotes from Altman's masterpiece Nashville. After the country music diva Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakley) is carried from the stage of the Grand Ole Opry after an assassination attempt, the aspiring singer Albuquerque (Barbara Harris) quickly picks up the mike and leads the gospel choir in “It Don’t Worry Me”.

The dispassionate panning shot that takes in several emergency operations as the surgeons speak offhandedly in M*A*S*H, also quoted by Mann, has the same effect. It’s not that Altman was callous or disrespected individual lives (the opposite was true), more that he recognized that one person’s confrontation with mortality is another’s cigarette break – and that the beat goes on. (Pictured above: Altman and his wife Kathryn Reed Altman.)

The dispassionate panning shot that takes in several emergency operations as the surgeons speak offhandedly in M*A*S*H, also quoted by Mann, has the same effect. It’s not that Altman was callous or disrespected individual lives (the opposite was true), more that he recognized that one person’s confrontation with mortality is another’s cigarette break – and that the beat goes on. (Pictured above: Altman and his wife Kathryn Reed Altman.)

Stuart (Fred Ward) and his buddies don’t let a little thing like a woman’s corpse curtail their fishing trip in Short-Cuts. Lady Sylvia (Kristin Scott Thomas) sleeps with a young American valet almost immediately after her husband is murdered in Gosford Park. Sentimentality in Altman amounts to the noble death of McCabe (Warren Beatty) in the Oregon snow in McCabe & Mrs Miller or Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) shooting his old friend Terry Lennox over a matter of honour in The Long Goodbye.

These are elements, negative and positive, of what made Altman’s films “Altmanesque”, a critical term that also conjures his demythicising of Hollywood genres and satirizing of cultural, social, and political institutions. Because vaguer, it is a term used less promiscuously than, say, “Hitchcockian”, “Kubrickian”, or “Spielbergian”, but it’s that very elusiveness and its sufficient familiarity that prompted Mann to use it as the organizing concept of “Altman”.

Having defined it playfully in a title at the start of the documentary, Mann asked such Altman alumni as Gould, Lily Tomlin, James Caan, Robin Williams, Sally Kellerman, Bruce Willis and Julianne Moore to state pithily what “Altmanesque” means to them. (Paul Thomas Anderson, the gifted director of ensemble films who’s generally considered Altman’s heir, answered with the word “Inspiration” when he, too, was asked.) Each of these talking heads informally introduces a chapter in Mann’s chronological history of Altman, which sadly skips his Kansas City upbringing. As it runs through the movies and traces Altman’s 1970s success, the devastating failure of Popeye, his subsequent exile in Paris, his resurrection with The Player, and his productive last 14 years, the doc can seem perfunctory and superficial. A future Altman documentary would do well to parse his auteur-ship and his battles with the studios.

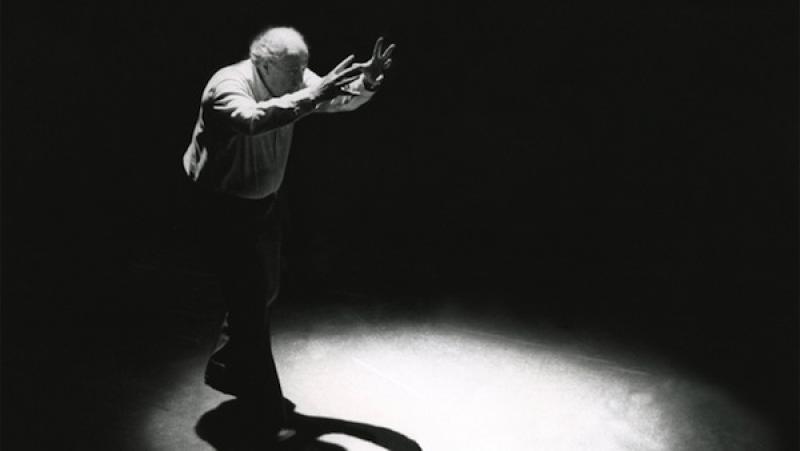

The actors’ words are less revelatory than those of his family members – for, above all, Altman is a family affair. The major narrator is Kathryn Reed Altman, the former model and actress who became his third wife in 1959 and was with him until the end: her last contribution, concerning the effect of seeing Brief Encounter on Altman and made by her on camera, is worth waiting for. (Pictured above: Altman at work; note the camera's new logo.)

The actors’ words are less revelatory than those of his family members – for, above all, Altman is a family affair. The major narrator is Kathryn Reed Altman, the former model and actress who became his third wife in 1959 and was with him until the end: her last contribution, concerning the effect of seeing Brief Encounter on Altman and made by her on camera, is worth waiting for. (Pictured above: Altman at work; note the camera's new logo.)

Two of Altman’s sons and his daughter Christine also chip in – one of the boys admitting that his father was wonderful on holiday occasions when they were young but barely around the rest of the time; Stephen and Robert welcomed the chance to join his crew since it let them get close to their dad. Home movie clips reveal that Altman, when he was there, was a loving father; a shot of him sitting on the stairs of his and Kathryn’s Malibu beach-house and peering at his extended clan toward the end of his life show how delighted he was to be surrounded by so many kids and grandkids.

I had the good fortune to spend three hours interviewing Altman at that house (not far from where Sterling Hayden’s suicidal Roger Wade staggers into the surf in The Long Goodbye) in June 1992, with Kathryn an occasional participant. I also talked to him twice at his Park Avenue office in New York. He gave of himself freely and warmly on these occasions, seeming to relish analyzing his films as if they were mysteries he had solved as he made them but still found amusing and intriguing to discuss, whether successes or failures. In Altman, there wasn’t a hint of the subtle condescension or defensiveness that characterizes some directors’ dealings with the press. He has frequently been described as “mercurial” and as a “maverick”, but what a director he was – and what a thorn in the side of Hollywood conservatism and elitists and ideologues everywhere.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Train Dreams review - one man's odyssey into the American Century

Clint Bentley creates a mini history of cultural change through the life of a logger in Idaho

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Palestine 36 review - memories of a nation

Director Annemarie Jacir draws timely lessons from a forgotten Arab revolt

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Die My Love review - good lovin' gone bad

A magnetic Jennifer Lawrence dominates Lynne Ramsay's dark psychological drama

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

Bugonia review - Yorgos Lanthimos on aliens, bees and conspiracy theories

Emma Stone and Jesse Plemons excel in a marvellously deranged black comedy

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

theartsdesk Q&A: director Kelly Reichardt on 'The Mastermind' and reliving the 1970s

The independent filmmaker discusses her intimate heist movie

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

Blu-ray: Wendy and Lucy

Down-and-out in rural Oregon: Kelly Reichardt's third feature packs a huge punch

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

The Mastermind review - another slim but nourishing slice of Americana from Kelly Reichardt

Josh O'Connor is perfect casting as a cocky middle-class American adrift in the 1970s

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere review - the story of the Boss who isn't boss of his own head

A brooding trip on the Bruce Springsteen highway of hard knocks

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Blu-ray: Le Quai des Brumes

Love twinkles in the gloom of Marcel Carné’s fogbound French poetic realist classic

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

Frankenstein review - the Prometheus of the charnel house

Guillermo del Toro is fitfully inspired, but often lost in long-held ambitions

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

Add comment