Modigliani, Estorick Collection | reviews, news & interviews

Modigliani, Estorick Collection

Modigliani, Estorick Collection

A trailblazer of the avant-garde captivated by the art of the past

Modigliani’s short life was a template for countless aspiring artists who, in the period after his death in 1920, were only too willing to believe that a garret in Montmartre and a liking for absinthe held the secret to creative brilliance. While Modigliani certainly compounded poor health with a ruinous drink and drug addiction, this exhibition plays down his reputation as a hellraiser, suggesting instead an altogether quieter, although no less romantic character.

The work, too, follows a startlingly linear trajectory, suggesting a man with a rare sense of purpose that, one supposes, would have dwindled had the fug of intoxication been anything like permanent. Spanning the period from 1906 when he arrived in Paris from Italy, to 1919, the year before his premature death, the early drawings here come from the collection of his friend and patron Paul Alexandre and, with some later pieces from the Estorick Collection, provide an overview of the artist’s development. We see how Modigliani found his own idiom, and the sudden, almost magical blossoming that coincided with his relationship with the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, undoubtedly his greatest muse.

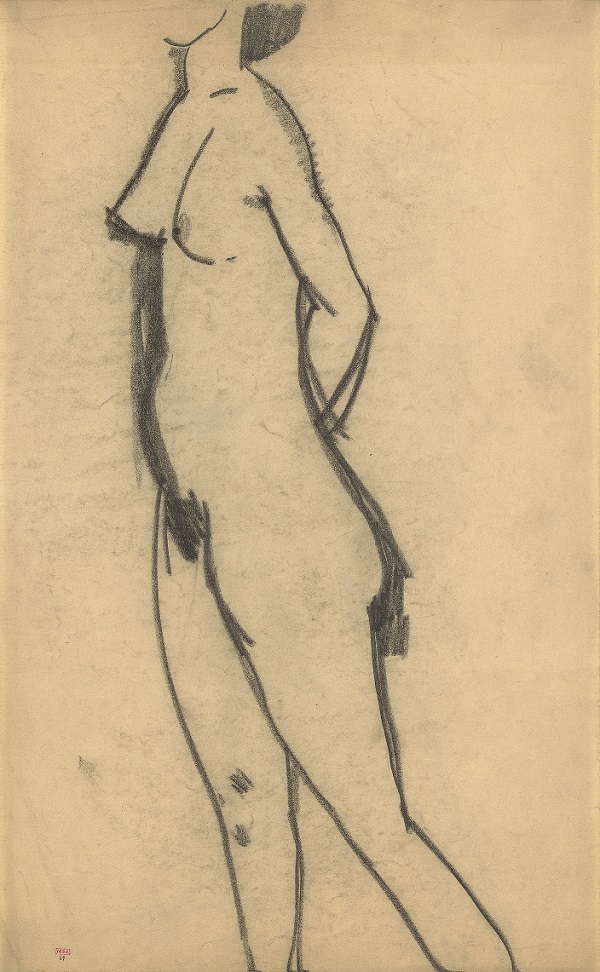

The earliest drawings are self-evidently so, the short, hesitant lines apparently bearing little relation to his more mature and better-known work in which elongated forms are described in exquisitely controlled, sweeping arcs. And yet in the considered, somewhat tentative execution of his Standing Female Nude of 1908 (Pictured right), we can surely see Modigliani testing the expressive possibilities of the human form, anticipating the grace and economy of line that began to emerge over the next couple of years.

The earliest drawings are self-evidently so, the short, hesitant lines apparently bearing little relation to his more mature and better-known work in which elongated forms are described in exquisitely controlled, sweeping arcs. And yet in the considered, somewhat tentative execution of his Standing Female Nude of 1908 (Pictured right), we can surely see Modigliani testing the expressive possibilities of the human form, anticipating the grace and economy of line that began to emerge over the next couple of years.

While these early nudes are ostensibly preoccupied with form, they are very often portraits at heart, each one conveying a powerful sense of the individual. In his eagerness to get to the essence of each subject’s character, Modigliani experimented with a battery of different media, the faintest pencil line striking a very different emotional pitch to the painterly applications of ink used in his sketch of Adrienne, c1909, in which bold, graphic strokes seem to be threatened with obliteration by heavily diluted washes.

In contrast to these vigorous early portraits, his studies of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, African, and ancient Egyptian art, reveal an interest in conventions of representation that seemed to Modigliani to offer universal truths about the nature and expression of beauty.

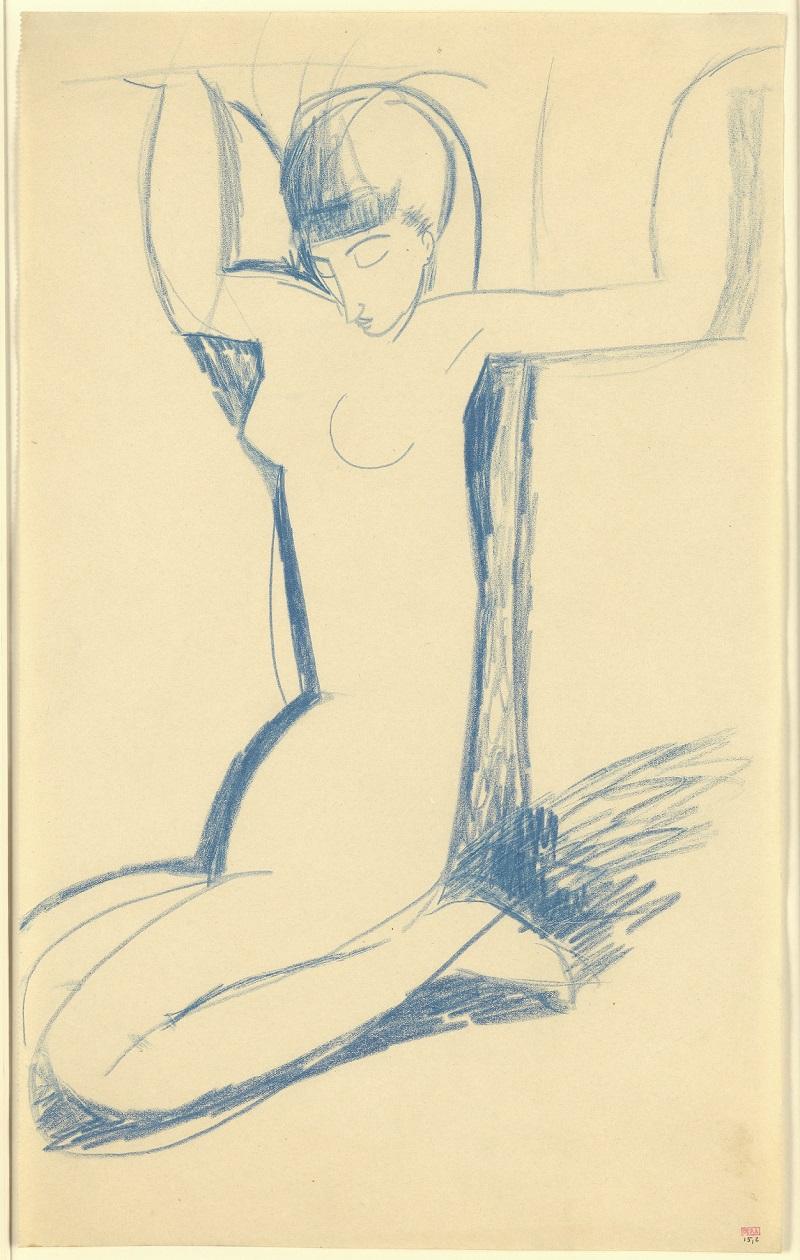

A drawing like Female Nude with Wing-like Arms (recto), c1910, anticipates his characteristically elongated style, the monolithic figure constructed from a series of arcs. There are no superfluous marks here, and the blank, mask-like face has taken its cue from the simplified representations typical of Egyptian and African art.

Somehow, in the Kneeling Blue Caryatid, c1911 (main picture), Modigliani has combined this sort of schematic treatment of the female figure with the piercing characterisation of his portraits. The result is a strange, bewitching creature, somewhere between a woman and an imagined, magical being, made of flesh, perhaps, but as a caryatid is by definition an architectural form there is a nagging suspicion that we are being seduced by a persuasive piece of sculpture.

While Modigliani’s semi-fantastical creatures took shape in his imagination, inspired by the collections of various Paris museums, it was the ethereal, but undoubtedly flesh-and-blood Anna Akhmatova who provided the bridge between real and imagined. For Modigliani she seems to have been the living embodiment of some ancient goddess, giving her face to his sphinx-like Woman Reclining on a Bed, c.1911.

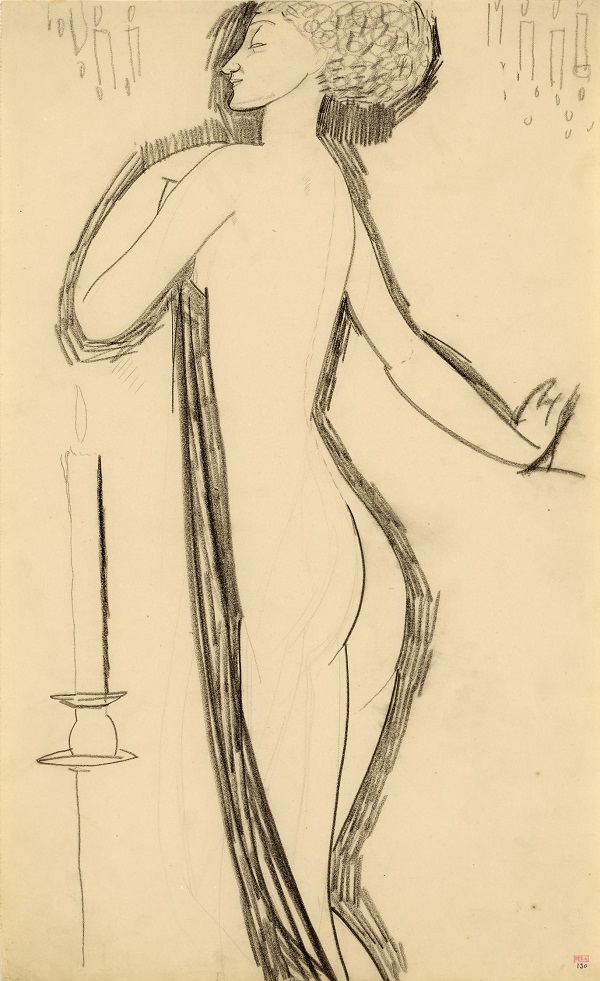

She appears again in Standing Female Nude in Profile with Lighted Candle, c1911 (Pictured left), simultaneously naturalistic and schematic, ambiguously located in space so that she appears to be at once a real woman and a painted figure, flattened to two dimensions, her posture recalling so many ancient Egyptian wall paintings. The candle seems at first incidental, or, at most, calculated to lend an atmosphere of magic and mystery, but it is essential to the uncertain nature of the image, the absence of shading heightening the sense of a two-dimensional, unreal form, while the most cursory lines beneath her elbow are enough to imply slight movement and the flickering of the candle. Even the deep shadow she casts on the wall is equivocal, and surrounding her like an aura, it begins to envelop her lower legs to become highly stylised, a graphic device more than an evocation of the effects of light.

She appears again in Standing Female Nude in Profile with Lighted Candle, c1911 (Pictured left), simultaneously naturalistic and schematic, ambiguously located in space so that she appears to be at once a real woman and a painted figure, flattened to two dimensions, her posture recalling so many ancient Egyptian wall paintings. The candle seems at first incidental, or, at most, calculated to lend an atmosphere of magic and mystery, but it is essential to the uncertain nature of the image, the absence of shading heightening the sense of a two-dimensional, unreal form, while the most cursory lines beneath her elbow are enough to imply slight movement and the flickering of the candle. Even the deep shadow she casts on the wall is equivocal, and surrounding her like an aura, it begins to envelop her lower legs to become highly stylised, a graphic device more than an evocation of the effects of light.

Anna Akhmatova is reputed to have had such a profound effect on Modigliani’s work that the ovoid faces and long, slender bodies for which he is best known came to the fore after they first met in 1910. But while his paintings, and especially his sculptures, see Modigliani’s characteristic visual language crystallised in sometimes androgynous and often impersonal renderings of the body, these drawings serve not only to elucidate Modigliani’s developing understanding of idealised beauty, but as fond, and very personal portraits.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment