Le Donne Curiose, Guildhall School | reviews, news & interviews

Le Donne Curiose, Guildhall School

Le Donne Curiose, Guildhall School

Youthful charm and a witty production keep Wolf-Ferrari's prolix comedy afloat

Scintillating gems scattered rather thinly through long-winded operas: that superficial impression of Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari’s often delectable music isn’t going to be changed greatly by seeing his first success of 1903, Le donne curiose (“Nosy Women”, perhaps, or, if you want a better English title “The Merry Men of Venice”).

Perhaps a music college’s first duty to budding opera singers is to make them feel, or seem, comfortable on stage; their whole lives up to that point have been about studying music, not drama. Past student productions have pointed up the fact that if the performers aren’t relaxed enough not to overdo it, certainly in comedy, the audience won’t go with them. Last night, in a cast with a few first-rate replacements for Monday’s team A, director Stephen Barlow hit the mark throughout, making of the nine principals of uneven vocal talent a true ensemble. In this he was vibrantly assisted by Yannis Thavoris’s 1970s designs (did anyone else of my age have a bedroom entirely in orange?). The malleable set offers one remarkable coup, a swivel from club entrance to club proper, the sort of thing that would get Met audiences applauding. The gags, not least Arlecchino's fart to two bassoons and the threat of kicking a football into the audience, are always neatly timed to the music.

Barlow's set-up is charming and funny. The first two-thirds of Wolf-Ferrari’s delightful Overture are accompanied by tourists buying carnival masks, postcards and gondoliers’ outfits from a Venetian shop while men furtively go through the door at the back and suspicious women try to see what’s going on. Then we have the film titles for an Italian sitcom, its stars grinning at the camera. The dramatis personae are assorted businessmen and their aides, and four women – two wives, a pert daughter and a mezzo servant (pictured left from top: Bethan Langford, Elizabeth Karanyi, Nicola Said and Katarzyna Balejko). The line-up of Verdi’s Falstaff, in short, without the main character – though one of the evening’s two most striking vocal stars, and certainly the most charismatic, bass-baritone Milan Sijanov as Arlecchino, could take on that role right now.

Barlow's set-up is charming and funny. The first two-thirds of Wolf-Ferrari’s delightful Overture are accompanied by tourists buying carnival masks, postcards and gondoliers’ outfits from a Venetian shop while men furtively go through the door at the back and suspicious women try to see what’s going on. Then we have the film titles for an Italian sitcom, its stars grinning at the camera. The dramatis personae are assorted businessmen and their aides, and four women – two wives, a pert daughter and a mezzo servant (pictured left from top: Bethan Langford, Elizabeth Karanyi, Nicola Said and Katarzyna Balejko). The line-up of Verdi’s Falstaff, in short, without the main character – though one of the evening’s two most striking vocal stars, and certainly the most charismatic, bass-baritone Milan Sijanov as Arlecchino, could take on that role right now.

The patter and parrying of Verdi’s miraculous last score are emulated, though not alas the pith; Wolf-Ferrari’s own dimension is an early neoclassicism pipping his fellow Italian-German Busoni to the post, well in advance of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos and Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. It could have done with more spring and lightness of touch from Mark Shanahan in the pit, though he did get the Guildhall Orchestra to convey the atmosphere and romanticism of Act (here “Episode”) Three’s night in Venice. Goldoni’s 18th century inclusion of characters from the commedia dell’arte has to do without the original improvisation, but it’s fun to catch their Venetian dialect – and it’s a joy to hear well-projected and clearly well-understood Italian between two ENO operas doggedly in English (Puccini’s La Bohème and Verdi’s The Force of Destiny, opening on Monday). Language coach Matteo Dalle Fratte has done excellent work here.

Nothing much happens: the men meet to eat pizza and to celebrate football, fast cars and amicizia (“friendship”); the curiosità of the women leads them to imagine floozies, occult dabbling and buried treasure. It takes them an awfully long time to see what’s through the keyhole, but most of that time – at least until the later stages of the last act – is beguilingly spent. Do the women get to join the club at the end? Of course not, but then this version is set in 1970s Italy, and to judge from RAI now, feminism still doesn't have that much of a hold there.

Nothing much happens: the men meet to eat pizza and to celebrate football, fast cars and amicizia (“friendship”); the curiosità of the women leads them to imagine floozies, occult dabbling and buried treasure. It takes them an awfully long time to see what’s through the keyhole, but most of that time – at least until the later stages of the last act – is beguilingly spent. Do the women get to join the club at the end? Of course not, but then this version is set in 1970s Italy, and to judge from RAI now, feminism still doesn't have that much of a hold there.

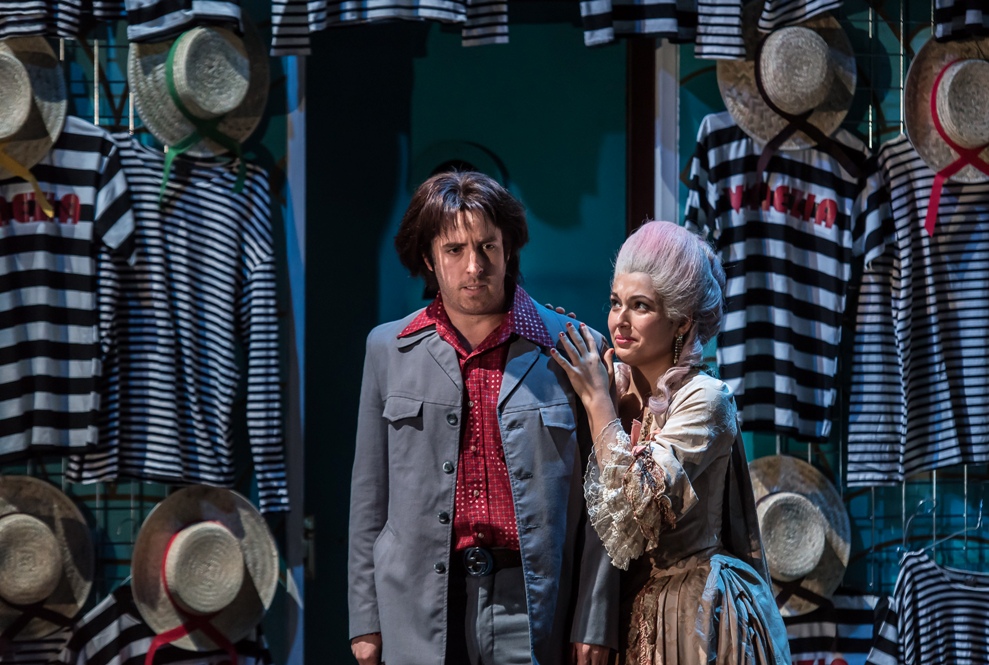

It’s frustrating that Wolf-Ferrari refuses to settle on a proper set-piece or a musical highlilght in “Episode” One, but the second opens out to a wonderful ensemble around the spaghetti lunch in Eleonora’s kitchen, Wolf-Ferrari’s harmonic sideslips adding piquancy, and a very pretty duet for the young lovers. Vocally, second-cast tenor Elgan Thomas (pictured above with Nicola Said) steals the show here: he’s a fully-fledged tenore di grazia who can both grandstand, at least as much as the composer lets him, and sing sweet, soft nothings as girlfriend Rosaura (Nicola Said) hands him the lunchtime plates to dry.

Of the women, Bethan Langford as chief housewife shows the most promise, but that’s almost irrelevant when they all work so well as an ensemble. There are other promising baritones among the men, whose characters aren’t so fully-fledged. Although it only has one chorus of even less consequence than the ones in Mozart’s Così fan tutte, Le donne curiose is otherwise the perfect opera for student teamwork. Next, please, if Glyndebourne won't do it, a double bill of Busoni’s Arlecchino and Turandot.

Next page: listen to Toscanini conduct the Overture to Le donne curioseToscanini in 1947 conducting the Overture to Le donne curiose

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Comments

I think the author of the

Thanks for the correction,

Thanks for the correction, now made in the text. Easily done, perhaps, but important to get it right.