The Homecoming, Trafalgar Studios | reviews, news & interviews

The Homecoming, Trafalgar Studios

The Homecoming, Trafalgar Studios

Jamie Lloyd's bold production makes Pinter freshly unsettling

Welcome to the hellmouth. In Jamie Lloyd’s startling 50th anniversary revival, the seething, primal hinterland of Pinter’s domestic conflict is made flesh: the metal cage surrounding an innocuous living room glows a devilish red, sulphur-like smoke belches from the ether, and snatches of Sixties music distort into horror film cacophony. Purists may carp, but it gives a long-revered play a welcome shot of adrenaline.

Lloyd, in concert with Soutra Gilmour (design), George Dennis (sound) and Richard Howell (lighting), has created a memorably cinematic haunted house. At times the bold, expressionistic presentation threatens overkill, but it does vividly illuminate the desperate alienation fuelling the family’s verbal warfare. There’s no safe distancing, rather we’re plunged into the depths of their psychological torment. Pinter’s elliptical exchanges remain riveting, as Lloyd’s additions don’t offer concrete explanations – that would be sacrilege – but a visceral experience of the roiling subtext.

As fading patriarch Max, Ron Cook is both booming fantasist, spinning yarns about his important past, and helpless widower, hollowed out by the loss of his wife and the nagging knowledge that his possession of her wasn’t total. Gary Kemp’s prodigal son Teddy, returning to his Hackney home after making it big as a philosophy professor in America, is all bluster and condescending blitheness, but his façade is easily punctured by those who’ve known him since birth. It’s the dark mirror of the regression that often results from a familial homecoming.

As fading patriarch Max, Ron Cook is both booming fantasist, spinning yarns about his important past, and helpless widower, hollowed out by the loss of his wife and the nagging knowledge that his possession of her wasn’t total. Gary Kemp’s prodigal son Teddy, returning to his Hackney home after making it big as a philosophy professor in America, is all bluster and condescending blitheness, but his façade is easily punctured by those who’ve known him since birth. It’s the dark mirror of the regression that often results from a familial homecoming.

The most striking pair are John Simm and Gemma Chan as insouciant brother Lenny and Teddy’s sphinx-like wife respectively (pictured above with Gary Kemp). Swaggering in spiffy suit and chillingly insouciant when relating his penchant for misogynistic violence, Simm lends the deadpan a razor-sharp precision, horrifying statements queasily framed by a demonic grin. But his mania is revealed by one of Lloyd’s nightmarish breaks, as Lenny furiously wrestles with a clock like it’s a bomb he can’t defuse. Chan, meanwhile, is the icy counterpoint to the hotheaded, pugilistic bullying. While the gender politics of the play remain debatable, here Ruth calculatedly exploits the men’s need for both mother and lover, manipulation flowing both ways. She ascends to the throne that is Max’s armchair with majestic certainty.

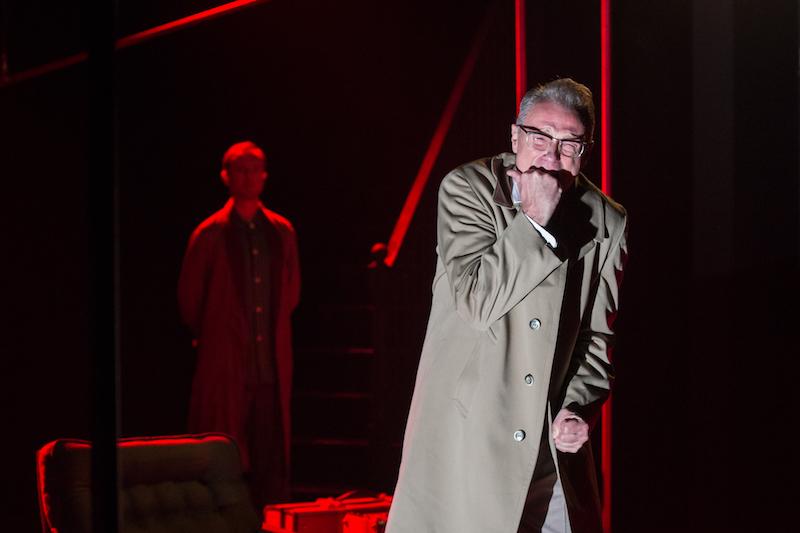

Lloyd also interrogates the traditional notion of masculinity. Keith Allen’s closeted chauffeur Sam proves a match for brutish ex-butcher Max, Simm’s menacing Lenny (pictured left) is disarmed by Ruth’s directness, and Lloyd plays up the absurdity of younger son Joey’s obsession with boxing. In John Macmillan’s reading, Joey is a delusional dullard, easily tamed.

Lloyd also interrogates the traditional notion of masculinity. Keith Allen’s closeted chauffeur Sam proves a match for brutish ex-butcher Max, Simm’s menacing Lenny (pictured left) is disarmed by Ruth’s directness, and Lloyd plays up the absurdity of younger son Joey’s obsession with boxing. In John Macmillan’s reading, Joey is a delusional dullard, easily tamed.

There is breathing space for Pinter’s deconstruction of British niceties, with small talk and exchange of everyday items – a glass of water, a cigar – subversively upended. Lloyd choreographs them into striking tableaux, mapping out the minute but hotly contested power shifts. He’s alert to the play’s revolutionary notion that tradition can stifle and damage rather than cement – “Who can afford to live in the past?” – making it clear that while Ruth fills a ghostly space by taking the place of a lost wife and mother, she leaves her own husband and children bereft.

This is more than a masterful revival – it’s a rebirth. Rather than looking back at a turbulent period, Lloyd has imbued this changing world with fresh, apocalyptic fervour. If that occasionally competes with Pinter’s distinctive hyperrealism, it also honours it, lending the familiar nastiness a mythical power.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment