10 Questions for Artist Clare Woods | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Artist Clare Woods

10 Questions for Artist Clare Woods

The sculptor turned painter talks about her monograph, working with her husband, and the artists who inspire her

Visceral and vividly colouristic, Clare Woods' paintings are at once abstract and figurative, perpetuating traditional genres but simultaneously occupying a less easily defined area of artistic practice. She puts innocuous or ambiguous subject matter into tension with titles and forms that suggest dark undertones, while big, universal themes are treated with the immediacy of personal experience.

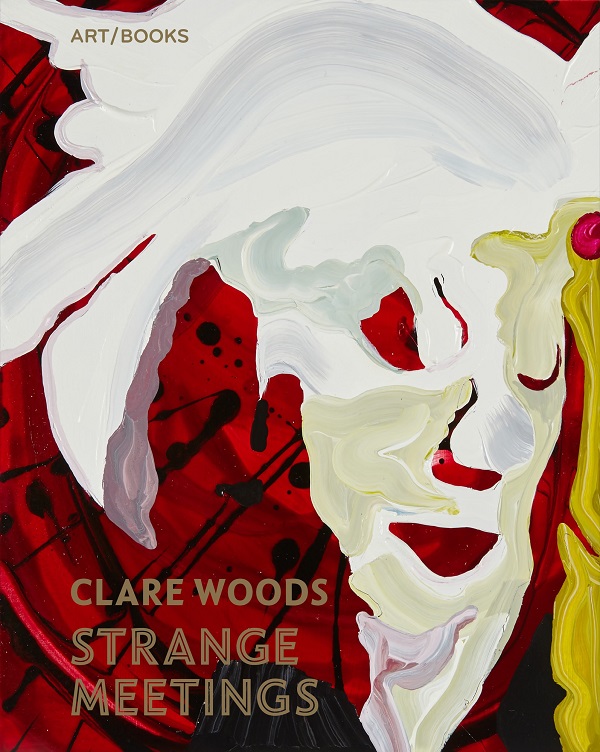

A graduate of Bath College of Art and Goldsmith's College, London, Woods (born 1972) has worked across a range of media, producing posters and billboards, prints and drawings. Regarded as one of the most important painters working today, she was commissioned by the Contemporary Art Society to make a ceramic mural for the London 2012 Olympic Park, and her work is included in permanent collections here and abroad. An exhibition featuring works by Woods and her husband the sculptor Des Hughes (born 1970) is currently at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, and her monograph, Strange Meetings, is published this month by Art / Books.

FLORENCE HALLETT: You trained as a sculptor and your methods and preoccupations continue to relate to sculpture. So why are you a painter?

CLARE WOODS: I used to make wooden objects that looked like a set of stairs or a tower - things that looked like they existed in the real world - and then paint them. And from there I started making MDF cubes, which I painted. As a student I also started looking at billboards – I always wanted to work big. At university I was always trying to push photographs to be three metres long and always trying to work on a larger scale.

I was really crap at sculpture, I was really bad. In my head I knew how I wanted things to work, but they never did and I had to cut down the many possibilities that exist for making an object – possibilities with materials and scale, for example. With painting there are fewer possibilities.

I was really crap at sculpture, I was really bad. In my head I knew how I wanted things to work, but they never did and I had to cut down the many possibilities that exist for making an object – possibilities with materials and scale, for example. With painting there are fewer possibilities.

I still don’t really feel like a painter, I still feel that I’m making objects. The panels I work with are made from aluminium, and I work on them flat, on trestles, so they become like a table (main picture). I don’t put them on the wall until they’re finished and I don’t really look at them as an image; its about the process, its about how the brushmarks allow you to believe that this is a circle, or this is a sphere, or this is a hand (pictured above right: Wrong Box, 2014).

And you use techniques that are more sculptural than painterly – it’s construction work

Yes, I tape the paintings up with masking tape, I cut the masking tape, I take bits of masking tape off, I paint, then I take another bit of masking tape off: its not about the image, its more about the construction of the paint. The whole process is very broken down, I’m photographing, finding photographs, drawing, working from source material, and then the painting stage is very much a formal process of colour and brushmarks - that’s all I’m really thinking about when I paint.

The Sleepers, at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, is a joint show with your husband the sculptor Des Hughes, in which you both respond to the gallery’s collection of modern British art. Was this dialogue with the Pallant collection the driver for the exhibition?

Using their collection is part of the show but not the main driving force. Des and I have been together 25 years and we’ve never had a show together: we’ve been in group shows and last year we moved into a studio together having never shared a studio, so it was quite a big change. Pallant House Gallery invited us to do a show together because they have got some quite incredible things in their collection, which we both have some history with. They’ve got a Paolozzi that I’ve painted before and they’ve got a Henry Moore that I’ve painted. And in Chichester Cathedral there’s the Arundel tomb, that Philip Larkin wrote the poem about: Des has worked with that imagery before.

I know the gallery very well and I really like it as a historic domestic space. The scale is modest, which forced me to make smaller work, which is good. I know the director Simon Martin quite well and he wrote a piece in the book. It’s a conversation that’s been going on for years, so it was just the right time to work with him and do the show (pictured below left: A Push and a Shove, 2015, on show at Pallant House Gallery).

I had been looking at photographs of Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson when they first got their studio together in Hampstead and how they would have one of his paintings with one of her sculptures propped up in front of it on the mantelpiece. We have a bit of that going on at home and in the studio, and I thought it would be great if we could show our work together because there are so many similarities.

I had been looking at photographs of Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson when they first got their studio together in Hampstead and how they would have one of his paintings with one of her sculptures propped up in front of it on the mantelpiece. We have a bit of that going on at home and in the studio, and I thought it would be great if we could show our work together because there are so many similarities.

The way that Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson displayed their work together in the studio was explored in Tate Britain’s Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World last year. It was immensely fertile ground for them. Tell me a bit more about how this dynamic inspired your own show and how it connects to your relationship with your husband as a sculptor?

I realised that’s what we’ve been doing for years. At home there’s always something that I’ve drawn propped up on a shelf and then there’s something that Des has made in front of it. I had never really noticed that relationship and actually even up to a couple of days before we were hanging the show, I was saying, “that sculpture looks so like that painting, I’ve never noticed that”. It’s formal as well as conceptual. So the show developed very much with those photographs of Hepworth and Nicholson’s studio in mind.

In the catalogue to the Tate's Hepworth show, there’s an essay about how she photographed her work and was very specific about how the work was photographed. I’ve always thought about sculpture when I’m making my paintings. I want people to move around them: you don’t see it instantly, it is like looking at a sculpture, there’s not an optimum viewpoint and you need to work with it a bit to get it. After reading the essay, I went back to look at those studio shots of Hepworth and Nicholson and realised that maybe they are more contrived than they appear to be.

She definitely influenced him and he influenced her, and it was that relationship and how it influenced the work that I found interesting. Maybe it’s a subliminal thing – with Des and I, it wasn’t like we said, "we are going to do this show together, what are you going to make and what am I going to make?" We just carried on making our work as normal.

Everyone who writes about you mentions your studio, particularly the way you collect all sorts of images on a wall.

We moved to a new studio a year and a bit ago and it’s this huge industrial unit. It’s amazing, it’s a huge space so we were able to just divide it up. There are two small rooms that we can keep really warm and that’s where a lot of drawing’s done and a lot of thinking – I’ve never had space in a studio before. Now I can leave stuff out which has been incredible and has really changed the way that I work. I have this whole room where I’ve just got a printer and some books and I can put things on the wall, which has been really good. There are things that I’ve been collecting for years, I’ve collected over 20 years’ worth of images and things I’ve always wanted to work with. But it’s as if I haven’t been ready to do it, my practice has had to change before I've felt able to start working with some of this imagery.

You explore big, universal themes, but to what extent is your work autobiographical?

It’s totally autobiographical. I was really ill from 2011 to 2013, I had to have my whole colon taken out. I was properly ill, seriously ill. It totally changed my work. Everything about it changed, it became very visceral, very internal. I kept my colon in a sweet jar for a year and was drawing it. That lead to working from autopsies, I painted and drew lots of autopsies, and the structure of the body and the colour of the body with no blood in it – yes it’s very linked, I can’t shift those things. The front cover of the book is a painting of the woman from the 7/7 bombing, July Sky, 2015 (pictured below right). I was caught up in all of that and it was one of the reasons I left London.

Your interest in other artists seems often to be a technical interest that goes beyond the formal or the conceptual. What form does your investigation of other artists' practice take? Is it research? Do you read technical reports?

Your interest in other artists seems often to be a technical interest that goes beyond the formal or the conceptual. What form does your investigation of other artists' practice take? Is it research? Do you read technical reports?

In 2011 I really wanted to know how to use orange and pink, I’ve always wanted to use these colours but have never been able to. I really, really looked at Francis Bacon’s work and his use of colour and particularly how he used those colours. And I got really interested in Giacometti because I love that idea of the space frame to contain an object. Bacon also uses it to contain a brushmark and I liked the connection between those two factors. So there’s a specific reason to look at most of the artists I look at. I’m not usually reading, I’m just looking. I’m looking at the other colours that allow the pink to exist, looking at the brushmarks, the line, how it’s used in what context it’s used, the tone and colour. It’s really, really formal. I’m not reading because I don’t want someone else to tell me, I want to work it out, I want to work out why for me that pink is important or why that frame contains that figure - what does that do for me? What is it doing that I want to use, or translate in some way.

The publication of your monograph, Strange Meetings, is a huge achievement and yet it came together very quickly. Can you tell me a bit about it?

The book is a huge milestone. It covers 25 years of work and is an overview of my practice so far. I think its strengths are showing the full range of works and how they inform the paintings - the posters, public commissions and all the other relationships and conversations that form the whole. I met with the publisher Andrew Brown at the end of October 2015 and the book was printed February 2016. It was an amazing moment and Andrew had real insight and a very active role in making the book.

I took the title from a war poem by Wilfred Owen, which is just another one of those grim poems about the trenches, and life in the trenches, the landscape and that displacement of belief or reality, so that’s why I wanted use it. I also used it as a painting title a while ago and so it just seemed right.

Painting is always being declared dead or at least in crisis. Do you have any observations about the current state of the medium?

Painting seems to be a lot more popular than it has been for a long time, if I’m being polite. When I was painting early on there weren’t many painters and there seems to be a lot of painting now. I don’t know… I see a lot of bad painting. And there are a lot of ceramics around at the moment. You wouldn’t have seen ceramics in an art fair 10 years ago, but now they are everywhere, bad ceramics. I don’t think it’s great. I like historic painting but there are many great painters that I look at that are still alive – I saw the Michael Simpson show at Spike Island, and there's Dexter Dalwood, another amazing painter. There are great painters still practising but there’s also a lot of shit.

What are you doing next?

I’m in a three person show at the Pier Arts Centre in Orkney, working with their collection. I am painting all of their Barbara Hepworth’s for the show. It’s great, really exciting - that’s in July. And I’ve got a one person show at Hestercombe in Somerset, which is a retrospective, it’s all my landscape works going back to 2000. There are a couple of new paintings but on the whole it’s mostly old work that’s been borrowed back.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Mickalene Thomas, All About Love, Hayward Gallery review - all that glitters

The shock of the glue: rhinestones to the ready

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Interview: Polar photographer Sebastian Copeland talks about the dramatic changes in the Arctic

An ominous shift has come with dark patches appearing on the Greenland ice sheet

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery review - absence made powerfully present

Illness as a drive to creativity

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Noah Davis, Barbican review - the ordinary made strangely compelling

A voice from the margins

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Best of 2024: Visual Arts

A great year for women artists

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet, Tate Modern review - an exhaustive and exhausting show

Flashing lights, beeps and buzzes are diverting, but quickly pall

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

ARK: United States V by Laurie Anderson, Aviva Studios, Manchester review - a vessel for the thoughts and imaginings of a lifetime

Despite anticipating disaster, this mesmerising voyage is full of hope

Add comment