David Jones, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester | reviews, news & interviews

David Jones, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

David Jones, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

Celebrated as a poet but forgotten as a painter: a timely reappraisal of a master of word and image

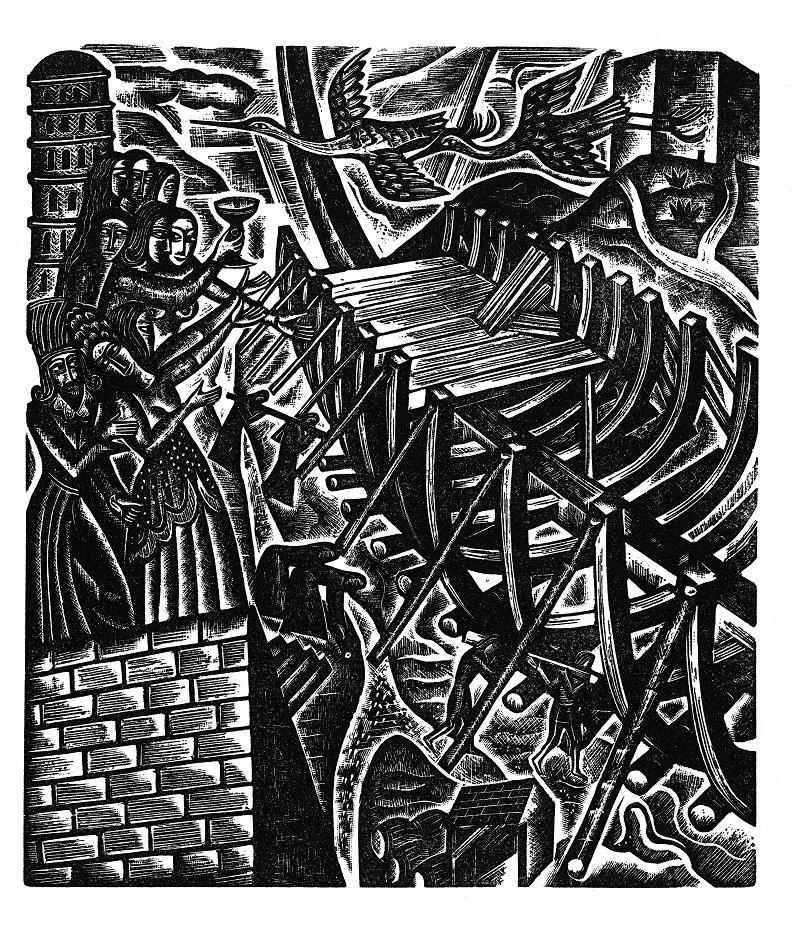

Switching between the orderly and the chaotic, David Jones’ depiction of Noah’s family building the ark immerses us in the drama of the moment while simultaneously holding us at some point out of time, to emphasise the story’s ancient roots.

Generating movement and tension through frequent tempo changes is a technique that recurs throughout David Jones’ work, and can be seen to riveting effect in the expressive brushstrokes of his Portrait of a Maker (Harman Grisewood), 1932, in which the image of his friend seems to shimmer in and out of focus, the smoothly painted sweep of the nose and brow echoing the curve of the hands, the lines of his lapels dissolving into the scumbled background. And in the preface to his poem In Parenthesis, 1937, his celebrated account of life in the trenches of World War I, Jones discusses his use of typographic idiosyncrasies to “indicate some change, inflexion, or emphasis”, explaining how the positioning of words and the insertion of space serves to “aid the sense and form”.

Generating movement and tension through frequent tempo changes is a technique that recurs throughout David Jones’ work, and can be seen to riveting effect in the expressive brushstrokes of his Portrait of a Maker (Harman Grisewood), 1932, in which the image of his friend seems to shimmer in and out of focus, the smoothly painted sweep of the nose and brow echoing the curve of the hands, the lines of his lapels dissolving into the scumbled background. And in the preface to his poem In Parenthesis, 1937, his celebrated account of life in the trenches of World War I, Jones discusses his use of typographic idiosyncrasies to “indicate some change, inflexion, or emphasis”, explaining how the positioning of words and the insertion of space serves to “aid the sense and form”.

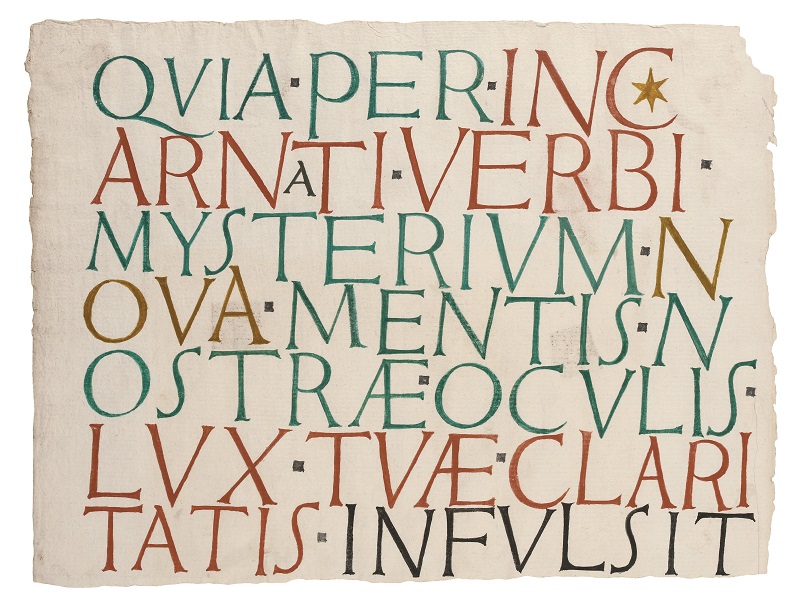

Jones' appreciation of the effects achieved by the considered positioning of words on a page, and his sensitivity to the relationship between words and image must have been stimulated through observation of his father’s work as a printer, and it certainly culminated in the painted inscriptions that he made from the 1940s onwards (pictured above right: Quia Per Incarnati, 1945). During the 1920s, Jones served what amounted to an apprenticeship with the sculptor and typeface designer Eric Gill, joining his Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic at Ditchling, East Sussex, where as part of a renewed interest in craft practice inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement, a revival of letterpress printing was in full swing. It was under Gill’s instruction that Jones learned wood-engraving, a technique favoured for book-illustration because it could be printed in combination with text.

The dense, dark wood engravings that Jones made to illustrate a series of three celebrated publications by the Golden Cockerel Press, including Gulliver’s Travels and The Book of Jonah, make a striking contrast to his illustrations for Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1928, for which he used the intaglio technique of copper-engraving to achieve a more fluid, open effect that permits considerably more white space than the relief method of wood-engraving can allow. In The Albatross, from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Jones’ customary use of an unusual viewpoint suggests the rolling waves, our encounter with the stricken albatross placing us at the very heart of the action. And far below, those strange ethereal figures reaching up towards us surely owe something to Matisse, or even Picasso.

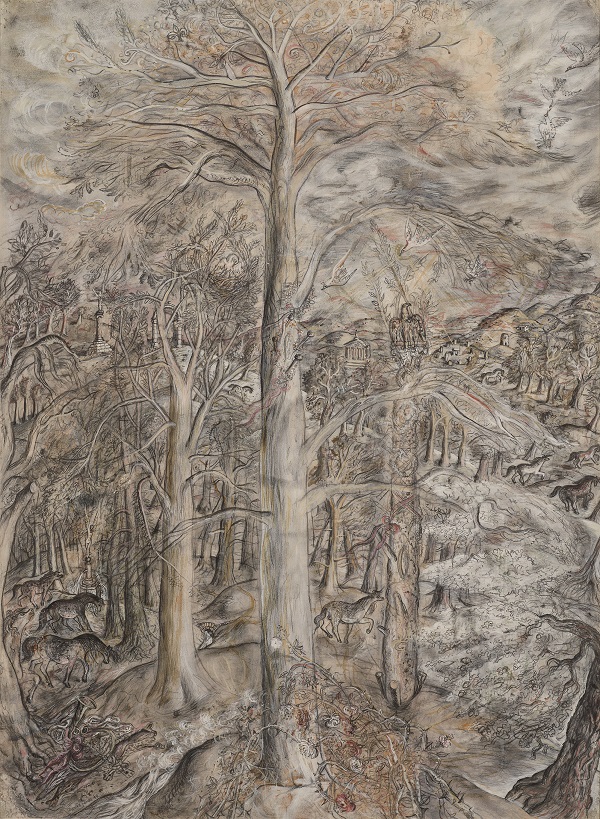

The sea is a recurring theme in Jones’ work, not least because it spoke to his sense of his own family’s maritime past. His maternal grandfather had been a mast-maker at Rotherhithe, and his father’s Welsh ancestry fuelled his sense of a romantic Celtic past which mingled with his experiences in the trenches to shape a poetic vision of shared history and experience. For Jones, the soldiers of his own generation were the direct descendants of the medieval knights, the animals on the hills, like the Roman horses running wild in Vexilla Regis, 1947-8, history’s constant, silent witnesses (pictured below).

In the later drawings and paintings, Jones’ deeply held Catholic faith combines with this sense of a collective history, with folk memory, biblical stories, myth and imagination vividly interwined. In Vexilla Regis, Calvary is set in the wilds of the Welsh countryside, a great tree pierced with nails to represent the crucifixion, a tangle of briars at its foot alluding to the crown of thorns. In the distance, classical ruins stand alongside a circle of standing stones; time here is indeterminate, beyond measure.

The heavy and exhausting symbolism of this piece is characteristic of Jones’ later work, and it is easy to see why his art has been all but forgotten since his death in 1974, its biblical, literary and cultural allusions running counter to the prevailing currents of the past 40-odd years. Even so, it is perfectly possible to read a painting like Flora in Calix-Light, 1950, laden as it is with religious symbolism, as a simple still-life. A central vessel, like a chalice on an altar, overflows with flowers, but any symbolism is chased away by the beautiful, yet profane detail of the window latch, which curls around like a stem, and becomes one with the tangle of flowers that surround it.

The heavy and exhausting symbolism of this piece is characteristic of Jones’ later work, and it is easy to see why his art has been all but forgotten since his death in 1974, its biblical, literary and cultural allusions running counter to the prevailing currents of the past 40-odd years. Even so, it is perfectly possible to read a painting like Flora in Calix-Light, 1950, laden as it is with religious symbolism, as a simple still-life. A central vessel, like a chalice on an altar, overflows with flowers, but any symbolism is chased away by the beautiful, yet profane detail of the window latch, which curls around like a stem, and becomes one with the tangle of flowers that surround it.

In fact, this exhibition suggests that Jones started painting still-lifes like this one under the influence of Ben and Winifred Nicholson, who he met in 1927 before being invited to join the Seven and Five Society, of which Ben was the chairman, a year later. Certainly the vibrant colour combinations that began to feature in Jones’ paintings, a vase of flowers before an open window a favourite theme, owe much to Winifred, while his energetic marine paintings, with their expressive use of paint, are also suggestive of her influence.

Neither a painter who writes poetry nor a poet who paints, David Jones is revealed here as a truly all-round artist of remarkable reach. And yet however accomplished his paintings, it is without doubt his prints that really fascinate, and are worth going back to time and time again.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment