Reissue CDs Weekly: Close to the Noise Floor | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: Close to the Noise Floor

Reissue CDs Weekly: Close to the Noise Floor

Thrilling celebration of the UK’s early indie-synth mavericks

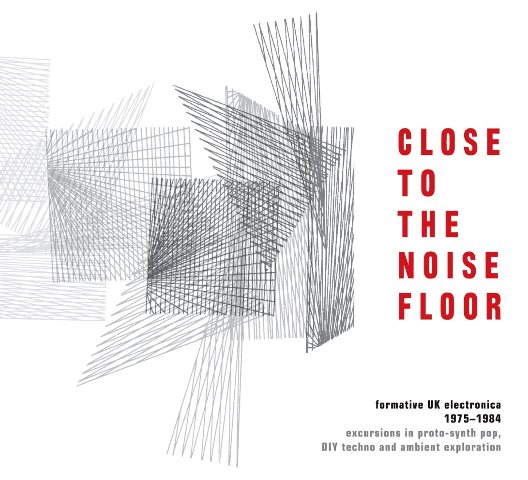

The immediate reaction to Close to the Noise Floor is “Why hasn’t anyone done this before?” This new four-disc set’s subtitle captures its objective in a nutshell: to collect Formative UK Electronica 1975–1984 – excursions in proto-synth pop, DIY techno and ambient exploration.

Close to the Noise Floor sets the moody electropop of Spöön Fazer’s previously unissued “Back to the Beginning” (1982) off against 100% Manmade Fibre’s fractured “Green for go” (also 1982). Adrian Smith’s fantastic “Joe Goes to New York” (1981) is an apocalyptic, powerful soundscape which would have not been out of place soundtracking Blade Runner. In the liner notes, Smith says it was recorded direct to cassette in one take with the background drone provided by a Coke can sat upon the keyboard of a WASP synthesiser.

Over its 61 tracks, Close to the Noise Floor takes a unique overview of a particular strand of British music. Some contributors like Blancmange and Orchestral Manouevres in the Dark, to varying degrees, normalised and broke into the mainstream. Others, such as Five Times of Dust, swiftly disappeared off most maps. There have been reissues of some of the more obscure names (mainly by non-UK labels), but such an overview has been lacking.The only previous corollary is the American multi-volume Messthetics series of CD comps which dealt with the whole of the British DIY scene rather than a single stylistic strand.

Over its 61 tracks, Close to the Noise Floor takes a unique overview of a particular strand of British music. Some contributors like Blancmange and Orchestral Manouevres in the Dark, to varying degrees, normalised and broke into the mainstream. Others, such as Five Times of Dust, swiftly disappeared off most maps. There have been reissues of some of the more obscure names (mainly by non-UK labels), but such an overview has been lacking.The only previous corollary is the American multi-volume Messthetics series of CD comps which dealt with the whole of the British DIY scene rather than a single stylistic strand.

Reasons for the lack were, in part, that taking on the task has been difficult due to the sheer effort in tracking down, say, Third Door From the Left, and then deciding what, by them or anyone else, is representative. Then, there is the problem of getting to grips with what was actually originally issued. "Issued" may not be the right word: at least half of those on Close to the Noise Floor recorded on and circulated their music on cassette by post. They lived in and subscribed to a dedicated DIY world in which it did not matter how many people heard what had been recorded. One of the issues has been cleverly sidestepped by letting the artists choose what they wanted to be included, and also giving them the chance to write their own commentary on their track.

Once the mind-boggling logistics have been acknowledged, it’s apparent that Close to the Noise Floor is no DIY release. Smart case-binding houses a 48-page book and the four discs, each in a bound-in slipcase. Clarity is further brought to what could be murky with a crisp design aesthetic in total sympathy with content and the era covered. This is an artefact. It is also a belated and neccesary corrective to such gee-whiz, golly-gosh archive romps as the BBC's fatuous 2009 Synth Britannia programme.

Most crucially, Close to the Noise Floor celebrates the music and the maverick spirits who made it. Synthesisers were becoming cheaper, as was home-recording equipment. Drum machines were more flexible. Electronic equipment could be bought mail order and assembled at home. The size of electronic instruments was shrinking and portability became an option not previously open. Bedroom recording was possible as was live performance. Commerciality was not a concern, though coverage of what was leaking out came from the weekly music paper Sounds and fanzines. And, as old-manish as stressing this is, these recordings were made before laptops and digital recording – the creative effort was palpable, possibly why some of it is so extreme. No one could stand lamely on stage doing nothing behind a laptop. The process of creation required very active engagement. This is not meant to be luddite, but to emphasise that any current similar-sounding music is not relevant to setting a context.

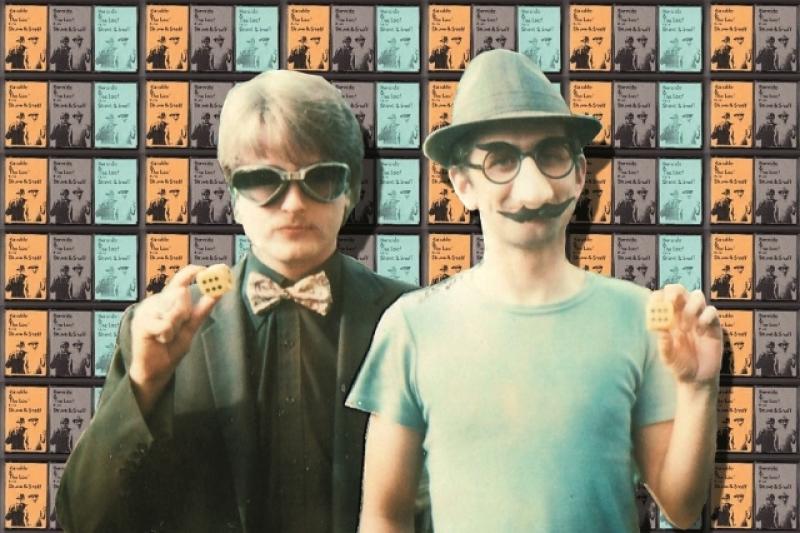

Although this music chose to settle at the margins, the weirdest aspect of spending 255 minutes with these 61 wilful sonic adventurers is just how listenable they all are. This despite themselves. While there is nothing which could be defined as dance music per se and there are excursions into the abstract, rhythm is an recurrent obsession. Bludgeoning, grinding, mechanised rhythm. Throbbing Gristle’s “What a Day” runs with this to result in an aural equivalent of having a wheel run repeatedly over the head. The deeply threatening “In the Army”, by Blah Blah Blah (pictured left in live performance), uses blooping synth as its rhythmic pulse.

Although this music chose to settle at the margins, the weirdest aspect of spending 255 minutes with these 61 wilful sonic adventurers is just how listenable they all are. This despite themselves. While there is nothing which could be defined as dance music per se and there are excursions into the abstract, rhythm is an recurrent obsession. Bludgeoning, grinding, mechanised rhythm. Throbbing Gristle’s “What a Day” runs with this to result in an aural equivalent of having a wheel run repeatedly over the head. The deeply threatening “In the Army”, by Blah Blah Blah (pictured left in live performance), uses blooping synth as its rhythmic pulse.

Much of the goal was to jolt potential listeners as much as possible, an aim in keeping the bleak moods and air of disatisfaction with the times running through the four discs. Cultural Amnesia have their “Materialistic Man”, John Foxx wishes for “A New Kind of Man” while Alan Burnham has a yen for “Music to Save The World by”.

With a track apiece from those collected, Close to the Noise Floor inevitably provides a taster. Renaldo and the Loaf, for example, made at least four cassette albums and three vinyl albums (plus one in collaboration with America’s The Residents). Some absences seem mysterious. Cabaret Voltaire do not appear, as don’t The Normal, Robert Rental and the very early Soft Cell. Track-by-track numbering in the book would have been good to help find the text on each cut. But these quibbles are small beer. The hugely important and utterly delightful Close to the Noise Floor is in prime position to become the reissue of the year.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Sad and Beautiful World: Mavis Staples offers words of wisdom

Soul sister sings on

Sad and Beautiful World: Mavis Staples offers words of wisdom

Soul sister sings on

theartsdesk on Vinyl 93: Led Zeppelin, Blawan, Sylvester, Zaho de Sagazan, Sabres of Paradise, Hot Chip and more

The most extensive, wide-ranging record reviews in the galaxy

theartsdesk on Vinyl 93: Led Zeppelin, Blawan, Sylvester, Zaho de Sagazan, Sabres of Paradise, Hot Chip and more

The most extensive, wide-ranging record reviews in the galaxy

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Suzanne Vega and Katherine Priddy, Royal Albert Hall review - superlative songwriters

Two brilliant voices fill the Royal Albert Hall

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Add comment