Wagner was never satisfied with Tannhäuser, and it’s not hard to see why. Essentially a study of the tension between sensual and spiritual love, it was composed at a time when, by his own later confession, he lacked the resources to deal properly (that is, improperly) with the sensual element, and even in any profundity – one might feel – with the spiritual. The piece went through numerous revisions, extensions, compressions, tinkerings of one sort or another. But what was left is a patchwork of early and late, conventional and inspired, and a sometimes painfully naïve morality which tends to leave you sorry for Wagner’s sex-fiend Venus and aggravated by her spiritual opposite number, the pure Elisabeth.

It looks like, and sometimes is, a director’s (hence an audience’s) nightmare. In Bayreuth, where I last saw it, it was set in a biogas recycling plant, Venus gave birth to the baby Jesus, watched over by Elisabeth as the Virgin Mary, and the reassuring message was apparently that profane and spiritual love are really much of a muchness.

At Longborough, to his credit, Alan Privett rejects any such evasion, though his slant on the Venus-Elisabeth axis is to say the least oblique. Venus, in his Victorianisation of Wagner’s medieval Thuringia, is an overgrown Alice on a swing, while Elisabeth is a twitching neurotic who has evidently been abused as a child by her uncle, the Landgrave. Leaving aside any possible implication that child molestation might offer us moral alternatives, the reading has a certain bizarre logic. On a stage where extreme Venusberg cavortings would be a shade cramped, it makes sense to see Venus as Tannhäuser’s middle-class bit on the side, and no less sense to find some edge to Elisabeth’s repressed purity and the ridiculous straitlacedness of the troubadours.

At Longborough, to his credit, Alan Privett rejects any such evasion, though his slant on the Venus-Elisabeth axis is to say the least oblique. Venus, in his Victorianisation of Wagner’s medieval Thuringia, is an overgrown Alice on a swing, while Elisabeth is a twitching neurotic who has evidently been abused as a child by her uncle, the Landgrave. Leaving aside any possible implication that child molestation might offer us moral alternatives, the reading has a certain bizarre logic. On a stage where extreme Venusberg cavortings would be a shade cramped, it makes sense to see Venus as Tannhäuser’s middle-class bit on the side, and no less sense to find some edge to Elisabeth’s repressed purity and the ridiculous straitlacedness of the troubadours.

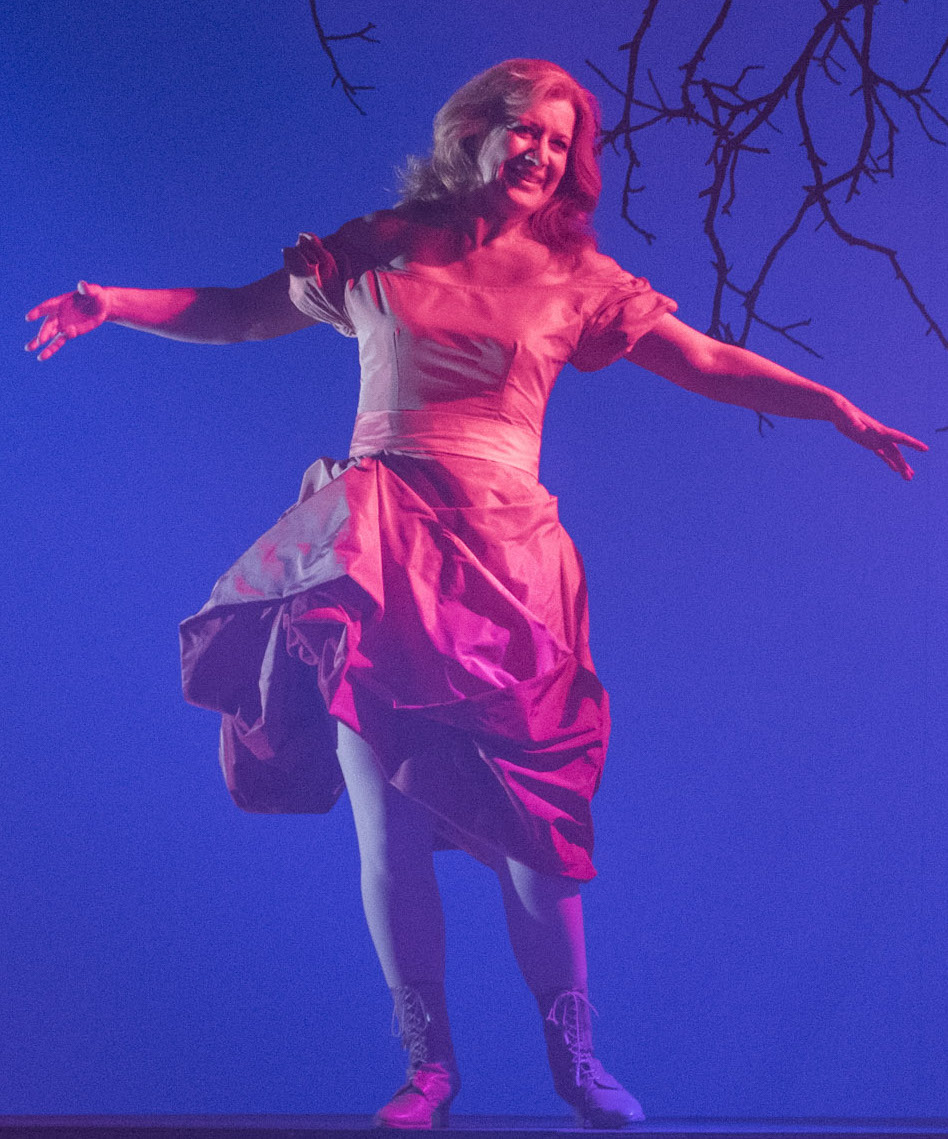

Privett’s Venus, the unusually (for a Wagner soprano) shapely Alison Kettlewell (pictured above), slips into the reading with precision, moving well, with just a flicker of vulgarity, and singing with fine, warm tone and admirable flexibility of expression for a character whose emotional tactics are, frankly, those of a bored housewife. His Elisabeth, Erika Mädi Jones, provides a marvellously interesting portrait of troubled repression, musically as well as visually. Her brilliant “Dich, teure Halle” on her first appearance (superbly accompanied under conductor Anthony Negus) shows an excitability that can quickly turn to revulsion at all the troubadours’ talk of high-minded love. Even the suggestion that she give out the prizes sets her cowering. Is her unexplained death suicide? We aren’t told, but might suspect.

The problem for both sopranos is the Tannhäuser himself, John Treleaven (pictured below), who cuts a shambling, unheroic figure in an ill-fitting green suit and forces his tone unnecessarily in this small, not very Wagnerian theatre (whether Neal Cooper, the second Tannhäuser – see above – will shamble, or force, remains to be seen). We get him initially front of curtain during the overture, in an extended dumb show as the composer composing and his wife (Venus, oddly) trying in vain to hand him a letter which turns out, presumably, to be from a lover (Elisabeth?). Why do good directors waste their energy on such stuff? It tells us nothing we need to know, and distracts from the music.

For the rest, the staging is crisp and compelling. Act II, with a lively young chorus and a strong team of suited troubadours, is as gripping as I’ve ever seen it, and an endorsement of Wagner’s early grasp of theatre even before his music was wholly up to the task. Hrólfur Saemundsson is a good, stylish Wolfram, not too interesting, just right; Donald Thomson a slightly growly Landgrave, which suits the character’s implied dodgy past; and Chiara Vinci a delightful, eye-catching shepherd boy, smartly directed.

For the rest, the staging is crisp and compelling. Act II, with a lively young chorus and a strong team of suited troubadours, is as gripping as I’ve ever seen it, and an endorsement of Wagner’s early grasp of theatre even before his music was wholly up to the task. Hrólfur Saemundsson is a good, stylish Wolfram, not too interesting, just right; Donald Thomson a slightly growly Landgrave, which suits the character’s implied dodgy past; and Chiara Vinci a delightful, eye-catching shepherd boy, smartly directed.

I also like Privett’s use of the auditorium for the pilgrims’ processions. Kjell Torriset’s designs are functional, not more, with some mysterious details, like a ladder to heaven that nobody uses and a large thurible swinging out excitingly over the audience, but no sign of the green shoots that betoken Tannhäuser’s supposed redemption. The real hero, though, is Negus himself, who inspires everyone to heights of musical excellence and seems able to lighten Wagner to the point where it sounds like music rather than indoctrination. I’ve heard more consistently polished wind playing in this theatre, but have not heard anywhere a Tannhäuser I’ve enjoyed so much.

Add comment