Marx: Genius of the Modern World, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Marx: Genius of the Modern World, BBC Four

Marx: Genius of the Modern World, BBC Four

Bettany Hughes probes the legacy of the co-author of the Communist Manifesto

An old subversive Soviet joke has Karl Marx coming back from hell, facing enormous crowds of very unhappy people and telling them, "Oh I'm so sorry – it was only an idea." But what an idea and ideas, as Bettany Hughes's film reminded us.

She took us on a very brisk canter through Marx’s life (1818-1883) and times, first visiting Trier where he was born into a bourgeois Jewish family, although his rather radical father had converted to Lutheranism to make his professional life easier under the Prussians. Evidently the young Marx was dashing, dapper and privileged – with a portrait to prove it – with little suggesting the poverty-stricken radical he was to become. We visited Berlin, Brussels, Paris and London, took in the revolutionary zeitgeist and learnt that Marx, a natural trouble-maker and big drinker, had even as a student brawled with aristocrats, having the scars to prove it.

His radical ideas prohibited an academic career; naturally he became a journalist. He was staggeringly prolific, publishing in newspapers in several cities, starting with the Rhineland News based in Cologne. As each outlet was shut down, Marx was forced to keep moving, eventually finding refuge in London. From 1845 when he renounced his Prussian citizenship he was effectively stateless.

His radical ideas prohibited an academic career; naturally he became a journalist. He was staggeringly prolific, publishing in newspapers in several cities, starting with the Rhineland News based in Cologne. As each outlet was shut down, Marx was forced to keep moving, eventually finding refuge in London. From 1845 when he renounced his Prussian citizenship he was effectively stateless.

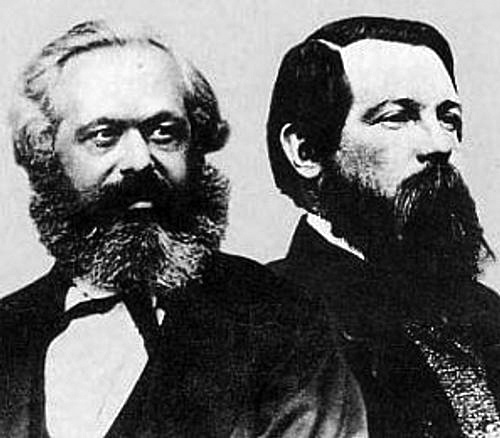

We started with the imposing grave in Highgate cemetery, the tombstone bearing the legend "Workers of All Lands Unite", although he was so obscure and poor when he died that the original gravestone was modest. Only 11 mourners turned up for the funeral but his great collaborator and financial supporter, his fellow German, Friedrich Engels, gave the eulogy (Marx and Engels, pictured above). Engels had money from his father’s textile business in Manchester, and was an acute observer of the misery and squalor that industry foisted on workers.

Marx married his childhood sweetheart Jenny, ironically herself from an upper class Christian background. They had six children all together, but Marx, according to the programme, had an illegitimate child with their housekeeper. His permanent exile in London was a sorrow to him, as were the deaths, exacerbated by his poverty, of three of his children.

Dermatologist Sam Shuster had spent nine years going through letters from Marx to determine what exactly what was the skin complaint that tortured him through adulthood; an unpronounceable and unrepeatable Latin name floated out in the interview, but evidently it was rare and hideously uncomfortable. Moreover it was a catalyst for self-loathing.

The script was a mishmash of clichés – times were tumultuous, ideas were big bold and dangerous, the world as we knew it was breaking down (was it not ever thus, this reviewer thought) and Marx’s name and work will endure through the ages. But the programme was nevertheless a tantalising attempt to explain Marx. The Communist Manifesto of 1848 which elucidated the class struggle was commissioned by the international Communist League, written in Paris with Friedrich Engels, and published in London in German. It's is only about 30 pages long, but thousands of pages were to follow. The academic talking heads pointed out that Marx had no solutions, but many questions; he was not the demagogue or fanatic of popular perception.

He was not, it was indicated, wholly opposed to capitalism but thought it inherently unstable, the plaything of alien forces, given to destructive cycles of boom and bust. What was most threatened was healthy human productivity; religion was, in that indelible phrase, the opium of the masses. All of this could not be more topical, considering current rage about the seemingly untouchable immorality of so much of big business and banks, not to mention growing social inequalities. Libertarian anarchists, utopian socialists, and communists across Europe attempted and failed to change society, as workers everywhere, victims of technological change, lost out to those who owned the means of production.

He was not, it was indicated, wholly opposed to capitalism but thought it inherently unstable, the plaything of alien forces, given to destructive cycles of boom and bust. What was most threatened was healthy human productivity; religion was, in that indelible phrase, the opium of the masses. All of this could not be more topical, considering current rage about the seemingly untouchable immorality of so much of big business and banks, not to mention growing social inequalities. Libertarian anarchists, utopian socialists, and communists across Europe attempted and failed to change society, as workers everywhere, victims of technological change, lost out to those who owned the means of production.

A rather terrifying map showed us that in modern times countries comprising a quarter to a third of the world described themselves as having Marxist regimes. There were even snippets of "The Song of the Volga Boatmen", amidst the usual irritatingly portentous doom-laden music that seems inevitable in such televisual histories.

Friedrich Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud are to come in Hughes’s Genius of the Modern World trilogy. What is it with these German writers?

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Add comment