Reissue CDs Weekly: Gilbert Bécaud | reviews, news & interviews

Reissue CDs Weekly: Gilbert Bécaud

Reissue CDs Weekly: Gilbert Bécaud

Dauntingly massive box set dedicated to 'Monsieur 100,000 Volts’

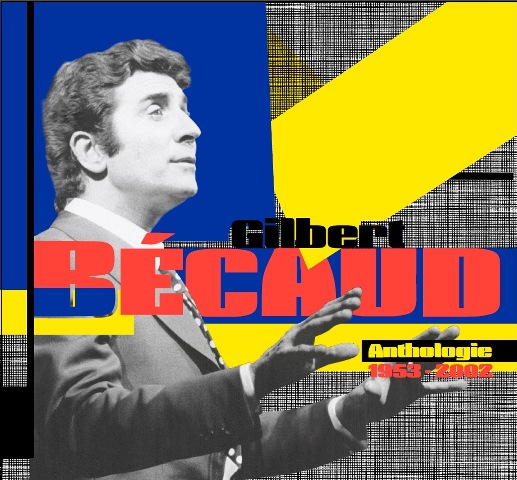

Anthologie 1953–2002 is a monster. A 20-disc set spanning almost 50 years, it tracks one of France’s most beloved singers and songwriters. Gilbert Bécaud died in December 2001, but songs from his posthumously released Je Partirai album are included. Fitting, as his music lives on and the release of this box set marks the 15th anniversary of his death.

Outside France, Bécaud is less well known. Though his “A Little Love and Understanding” single charted in Britain in 1975, he did not make a Charles Aznavour-style crossover to mainstream recognition in the Anglophone world. He’s never been given belated appreciation and the subsequent commodification as happened with Serge Gainsbourg. For France, he doesn’t quite fit the received notion of a chansonnier: the poet-like singer-songwriter with a strong personality standing apart from that of other performers. Figures likes Georges Brassens, (Belgium’s) Jacques Brel and Léo Ferré had instantly identifiable styles. Bécaud’s idea of branding was wearing a suit and tie, the latter usually a trademark spotted one. And, as Anthologie 1953-2002, makes abundantly clear, Bécaud is not instantly classifiable.

Bécaud was about his songs, a characteristic theartsdesk has previously noted. In their English-language versions, “What Now My Love”, "Let It Be Me" and “The Day the Rains Came Down” have become standards. Writing with Neil Diamond recognised that Bécaud’s songwriting had international appeal. He was also adaptable. During the Sixties’ yé-yé era he wrote for straight pop singer Richard Anthony and the earthy former rock ‘n’ roller Eddy Mitchell. Getting a handle on the essence of Bécaud has always been difficult.

Bécaud was about his songs, a characteristic theartsdesk has previously noted. In their English-language versions, “What Now My Love”, "Let It Be Me" and “The Day the Rains Came Down” have become standards. Writing with Neil Diamond recognised that Bécaud’s songwriting had international appeal. He was also adaptable. During the Sixties’ yé-yé era he wrote for straight pop singer Richard Anthony and the earthy former rock ‘n’ roller Eddy Mitchell. Getting a handle on the essence of Bécaud has always been difficult.

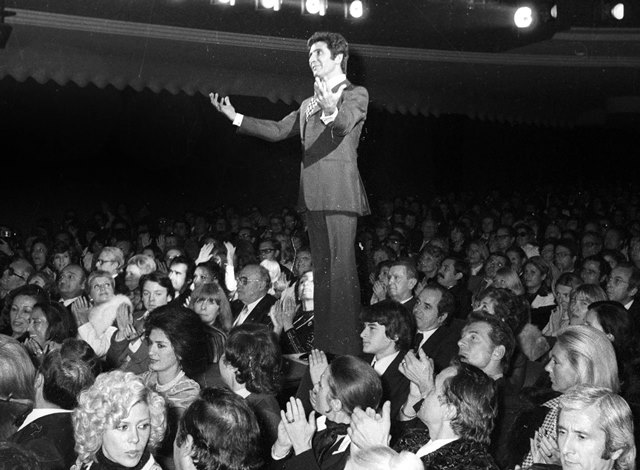

Bécaud was also about his powerful live presence. In person, he was dynamic and always electric. Indeed, he was known as “Monsieur 100,000 Volts.” The man born François Silly in 1927 took a little while to get there. Initially, he was not a performer and wrote for film and for others. Edith Piaf was an early adopter of his songs. His first release came in 1953, which is where Anthologie 1953–2002 begins.

The first recording heard is “Les Croix”, the topside of his first single, recorded on 2 February 1953. It is lush and, considering that French records were often still rickety sounding in the mid Sixties, surprisingly so. Fully orchestrated, with his deliberate delivery floating above strings, piano and muted woodwind, it sounds as if plucked from a film soundtrack. “Il Faut Bâtir ta Maison”, recorded at the same session, is more sprightly. It could have played over a bustling scene in a film: of people scurrying to work, or a shot tracking through a busy market. The lyrics of “Il Faut Bâtir ta Maison” were by Pierre Delanoë, Bécaud’s most long-term and principal collaborator. Delanoë had also written for Piaf and was as adept as Bécaud: Johnny Hallyday and Michel Sardou recorded his words.

As Anthologie 1953–2002 continues it becomes clear this adaptability suggests what Bécaud was about. Broadly, his recordings were orchestrated chanson-pop but he had an enviable capacity to insert a quintessentially French approach to songwriting into any style. In 1966, on disc seven’s “Le Petit Oiseau de Toutes les Couleurs” a then-contemporary Petula Clark-ish pep and swing colours the song but it remains as cinematically delivered – akin to a sung narration – as songs from ten years earlier or ten years later. This, then, is the essence of Bécaud: his ability to cast himself as a chronicler; the singer who bridges the gap between singer and audience or listener. The connection he makes is instant. It is hard to think of a British singer with a similar bearing. Perhaps, although he had an utterly different approach to song, Anthony Newley? (Pictured left, Gilbert Bécaud meets his audience in 1973)

As Anthologie 1953–2002 continues it becomes clear this adaptability suggests what Bécaud was about. Broadly, his recordings were orchestrated chanson-pop but he had an enviable capacity to insert a quintessentially French approach to songwriting into any style. In 1966, on disc seven’s “Le Petit Oiseau de Toutes les Couleurs” a then-contemporary Petula Clark-ish pep and swing colours the song but it remains as cinematically delivered – akin to a sung narration – as songs from ten years earlier or ten years later. This, then, is the essence of Bécaud: his ability to cast himself as a chronicler; the singer who bridges the gap between singer and audience or listener. The connection he makes is instant. It is hard to think of a British singer with a similar bearing. Perhaps, although he had an utterly different approach to song, Anthony Newley? (Pictured left, Gilbert Bécaud meets his audience in 1973)

For anyone who did not grow up with Bécaud, Anthologie 1953–2002 is daunting. Not only are there more than 400 tracks, the final three discs compile previously unreleased material and live recordings. Setting these in context is nigh impossible. It is also not a collection of his complete works. “A Little Love and Understanding” is not included and only four of his English-language recordings are heard. The striking design and evident care taken with the production (the remastering was undertaken from scratch) are set off against the missed opportunity the text represents. The box contains two hardback books: the second contains the CDs and the annotation. The first book is heavy on large-format photos, whole pages given over to graphics and a surface-level account of his life. In-depth text focusing on the music and the contents of the box set itself would have been much better.

Obviously, this is no entry point into Bécaud. But, no doubt, it will be in many French Christmas stockings. Only 4,000 though, as it is a numbered, limited edition. For non-French folks, beyond being stuffed with songs begging to be discovered, Anthologie 1953–2002 brings a welcome reminder that we know less than we should about our closest continental neighbour.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Soulwax’s 'All Systems Are Lying' lays down some tasty yet gritty electro-pop

Belgian dancefloor veterans return to the fray with a dark, pop-orientated sound

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Music Reissues Weekly: Marc and the Mambas - Three Black Nights Of Little Black Bites

When Marc Almond took time out from Soft Cell

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Mobb Deep - Infinite

A solid tribute to a legendary history

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Album: Boz Scaggs - Detour

Smooth and soulful standards from an old pro

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Add comment