St Lawrence String Quartet, Wigmore Hall | reviews, news & interviews

St Lawrence String Quartet, Wigmore Hall

St Lawrence String Quartet, Wigmore Hall

Haydn outstrips John Adams for the shock of the new

John Adams, let's face it, was the reason many of us came to hear the St. Lawrence String Quartet. Their performances and recordings as dedicatees of his labyrinthine First String Quartet and Absolute Jest, in which the four players function as soloist with orchestra, led to high hopes for the UK premiere of a second quartet. As it turned out, the yield was smaller beer than expected.

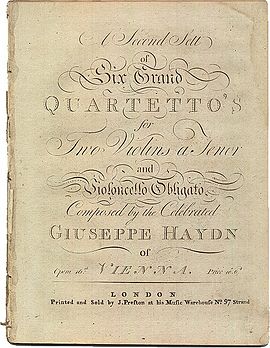

Not the curtainraiser, Op. 20 No. 1, which started with what seemed like a sledgehammer style to crack a piquant nut before the St. Lawrences justified the approach in the more adventurously written third and fourth movements, but its successor in terms of numbering. Haydn's quartets rarely get the concentrated position they deserve at the end of concerts, but if any of them works best that way, it's the early C major experiment with its wild, fractured "Capriccio" Adagio and the playful cleverness of its two-thirds sotto voce fugal finale.

Haydn's lovely, smooth opening with the cello taking the top line of the lower three instruments belies what's to come in all but the novelty of its grouping (there were further elegant games of this sort in the well-earned encore, the slow movement from Op. 20 No. 5, first violin Geoff Nuttall teasing us with a promised entry which was in fact taken by second Owen Dalby, with elaborations). Who could have anticipated the Sturm und Drang unisons of the C minor Adagio, the trilling, mournful melody which follows and the sudden shafts of sunlight, none of them resolved before the Minuet sidles in?

Haydn's lovely, smooth opening with the cello taking the top line of the lower three instruments belies what's to come in all but the novelty of its grouping (there were further elegant games of this sort in the well-earned encore, the slow movement from Op. 20 No. 5, first violin Geoff Nuttall teasing us with a promised entry which was in fact taken by second Owen Dalby, with elaborations). Who could have anticipated the Sturm und Drang unisons of the C minor Adagio, the trilling, mournful melody which follows and the sudden shafts of sunlight, none of them resolved before the Minuet sidles in?

The St. Lawrences' electric sense of drama, led by Nuttall with his highly-strung solos, made this a surprisingly strong successor in the second half to Janáček's First, "Kreutzer Sonata", Quartet, based – somewhat enigmatically – on Tolstoy's novella about murderous jealousy. If the brief suavity which settles after the highly-charged opening could have been gilded with greater sophistication, none of the sul ponticello (close-to-the-bridge) or spluttering pizzicato attacks missed their mark, culminating in a stupendous life-and-death drama in the finale.

What, though, to make of Adams's String Quartet No. 2? The spell of Beethoven which pulsed its way through Absolute Jest in quotations and rhythmic pulsings seems to be going through the hangover stage here. Adams has opened out his terms of reference to the Op. 110 A major Piano Sonata and a finale game with a brief "Diabelli" Variation, but this time he's too reliant on the dactylic rhythm which powers the orchestral work (Ninth Symphony scherzo or a feature of the Seventh, according to taste).

The screwing-up of harmonies and fragments yields diminishing returns, and though the St Lawrences delivered with manic energy when appropriate, there seemed little enough matter from the heart here. Let's say that this work stands in relation to its brilliant predecessor as Scheherazade.2 does to the first Violin Concerto: both sequels are eked-out games, while the "originals" remain untarnished as Adams at his adventurous best. It's simply a question of wanting to return and discover more. With the First Quartet, for me, that will always be the case; with the second, not so much.

- David Nice's blog on first acquaintance with the St. Lawrence String Quartet and Adams's earlier works for them

- Read more classical reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Classical CDs: Voice flutes, flugelhorns and froth

Baroque sonatas, English orchestral music and an emotionally-charged vocal recital

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

Kanneh-Mason, Britten Sinfonia, Shave, Milton Court - a grin and a big beaming smile

A pair of striking contemporary pieces alongside two old favourites

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

theartsdesk at the New Ross Piano Festival - Finghin Collins’ musical rainbow

From revelatory Bach played with astounding maturity by a 22 year old to four-hand jazz

Add comment