Darcey Bussell: Looking for Margot, BBC One | reviews, news & interviews

Darcey Bussell: Looking for Margot, BBC One

Darcey Bussell: Looking for Margot, BBC One

Investigating the incandescent, complicated life of the former Margaret Hookham

Classical dancers conventionally have the briefest of all performing careers in the arts, knowing from the very beginning that they'll be lucky to have 20 years of performing at the top of their abilities, after at least 10 years training from childhood onwards. But Dame Margot Fonteyn (1919-1991) was a phenomenon, dancing into her sixties, for reasons that this painful and affectionate programme tactfully explored.

Darcey Bussell comes across as someone who in spite of the usual dancer's injuries has remained optimistic and even upbeat on her own trajectory to the top, into retirement from performance, and on to a new career. So it was a ballerina leading this biographical essay interspersed with film clips of performances, and by Darcey’s many interviews with Fonteyn’s colleagues and her biographer who knew Fonteyn (pictured below) as the ballerina.

The only daughter of a mother wildly ambitious for her daughter’s success as a dancer, Margot Fonteyn (or Peggy Hookham, as she was before the name change imposed by Sadler’s Wells Ballet for professional reasons) studied dance from a very early age even as the family followed her father’s professional career abroad. But soon the child was home, and off on the 38 bus to Sadler’s Wells to learn to be a ballerina; by 16 she was a lead dancer. The whole company learnt their consummate professionalism the hardest way, in wartime touring conditions. The ballet’s post-war tour of America in 1949 was a triumph, and Margot was to grace the cover of Time magazine. By the 1950s, under the fierce energy of Ninette de Valois, they had migrated to the Royal Opera House and become the Royal Ballet, their Margot an undisputed star.

The only daughter of a mother wildly ambitious for her daughter’s success as a dancer, Margot Fonteyn (or Peggy Hookham, as she was before the name change imposed by Sadler’s Wells Ballet for professional reasons) studied dance from a very early age even as the family followed her father’s professional career abroad. But soon the child was home, and off on the 38 bus to Sadler’s Wells to learn to be a ballerina; by 16 she was a lead dancer. The whole company learnt their consummate professionalism the hardest way, in wartime touring conditions. The ballet’s post-war tour of America in 1949 was a triumph, and Margot was to grace the cover of Time magazine. By the 1950s, under the fierce energy of Ninette de Valois, they had migrated to the Royal Opera House and become the Royal Ballet, their Margot an undisputed star.

At the age of 18 she had had a fling with a dashing Panamanian, Roberto "Tito" Arias, son of the president of Panama and a student at Cambridge, which had come to naught. A search for connection haunted Margot: there was a long but ultimately failed affair with the married composer and head of music at the ballet, Constant Lambert, who went on to marry another. Her heart, her colleagues said, was soft as butter. When she finally split from Lambert she tore out all the pages in the books he had given her on which he had made notes.

Ballet was her family, but on a tour to New York in 1953 she re-met Roberto, by then ambassador to the UN and married with three children. He divorced, married Fonteyn in Paris in 1955, and became Panama’s ambassador in London. In 1959 she took an active part in a failed coup by her husband to overthrow the then government of Panama, and was arrested; she was not to be the First Lady of Panama but a disgraced prima ballerina.

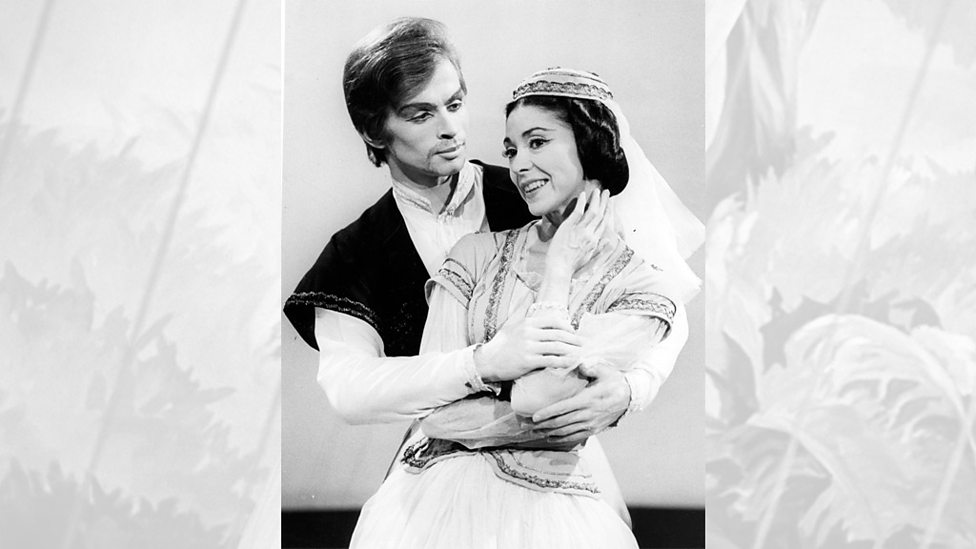

In yet another twist, the Russian defector Rudolf Nureyev then appeared on the scene in 1962, aged 23: “a wild animal let loose in the drawing-room... The relationship was incredibly close.” Did they or didn’t they? Rudy said disarmingly that in Russia we learnt from the older ballerinas, and of course he happened to be gay. The partnership was legendary, they danced together in 20 different ballets, but he was legendary in another way, given to tantrums: a naughty boy, we were told. A lover? Or the son Margot Fonteyn had never had, their sensuous relationship on stage professional, neither incestuous nor amatory? (Nureyev and Fonteyn, pictured below).

But Tito, left quadriplegic after a failed assassination attempt, also became the child she hadn’t had as she devoted herself and all her earnings to caring for him, living with him in a remote farm in the Panamanian countryside. To earn money she kept on dancing into her sixties; a colleague gasped when he saw her mangled feet, but she calmly said that her feet were where she had had her nervous breakdown. In 1990 the Royal Ballet put on a fund-raising gala in her honour. She was dead of cancer a year later.

But Tito, left quadriplegic after a failed assassination attempt, also became the child she hadn’t had as she devoted herself and all her earnings to caring for him, living with him in a remote farm in the Panamanian countryside. To earn money she kept on dancing into her sixties; a colleague gasped when he saw her mangled feet, but she calmly said that her feet were where she had had her nervous breakdown. In 1990 the Royal Ballet put on a fund-raising gala in her honour. She was dead of cancer a year later.

The tale of her incandescent dancing career was matched by the improbability of her personal life. Fonteyn was to find fame but not fortune. Was her gift more a curse than a blessing, especially as she said the happiest years of her life were her last decade as she tended her paralysed husband? Margot remarked wistfully but elegantly on the Parkinson show in 1975 that people thought of her only as a ballerina, and never as a person. We were led gently by the nose to an eventual conclusion that there is more to life than dance, even for dancers. The bland Ms Bussell presented it all with wide-eyed wonder at the talent and the tragedy. She was looking for Margot: but did she, or the viewer, find her?

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

Add comment