America After the Fall, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

America After the Fall, Royal Academy

America After the Fall, Royal Academy

Revelatory portrayal of the artistic response to the Great Depression

It may be a cliché to say that this is a “timely” exhibition, but America After the Fall invites irresistible parallels with Trump’s America of today.

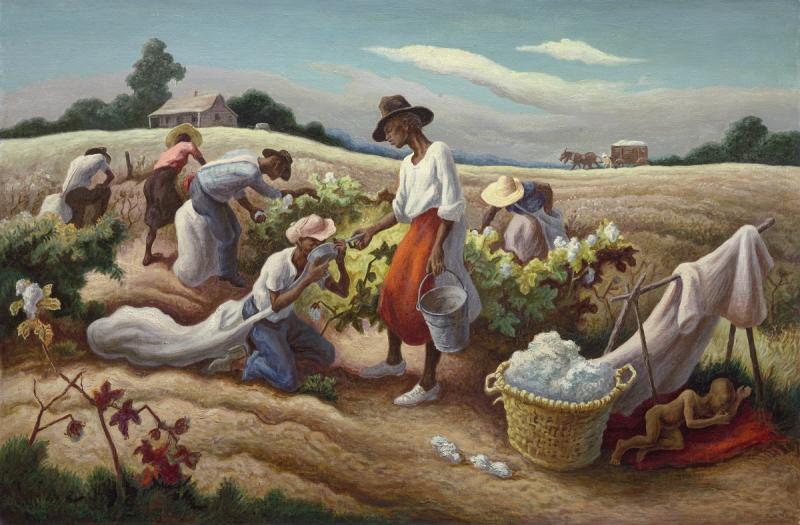

On the one hand these paintings celebrate American rural values – hard, honest work and frugality exemplified by the simple, homely aesthetic of American Shaker style, or local places and ordinary folk; on the other, they document gritty city life, the suffering and persecution of African Americans, industrial grandeur and the allure of escapist popular culture (particularly movies and jazz). At its heart is an earnest artistic quest for what it means to be “American” at a time of national and global uncertainty.

In fact, the genesis of the exhibition’s concept was the 2008 financial crash and parallels with the 1930s Depression. Its curator Judith Barter is also keen to showcase what is, for her, the richest decade in American art – exemplified by the number of talented artists whose visions jostled to capture the American imagination. As times were especially bad, support came from the Federal Artists Project (1935-43), which sustained thousands of artists through the period (although it showed a marked preference for “scene” painting).

In fact, the genesis of the exhibition’s concept was the 2008 financial crash and parallels with the 1930s Depression. Its curator Judith Barter is also keen to showcase what is, for her, the richest decade in American art – exemplified by the number of talented artists whose visions jostled to capture the American imagination. As times were especially bad, support came from the Federal Artists Project (1935-43), which sustained thousands of artists through the period (although it showed a marked preference for “scene” painting).

The Royal Academy’s fascinating and sharply focused exhibition features 45 pictures by 32 different artists. Some of these are household names – for example, Edward Hopper, Alice Neel and Georgia O’ Keeffe; others, such as Joe Jones or William H. Johnson, are barely known, even to an American audience. These artists seek to define American modernism, exploring a variety of styles from Regionalism, Surrealism to Pop Art and the stirrings of Abstract Expressionism – drawing on a wealth of European influences and employing healthy doses of American satire and irony. The quality of the pictures in the show varies enormously – there are some real duds, alongside works of real quality – but there is also the pleasure of engaging with the clarity of the show’s thesis, which is simply expressed through thematic sections (and enhanced by the elegance of the exhibition design).

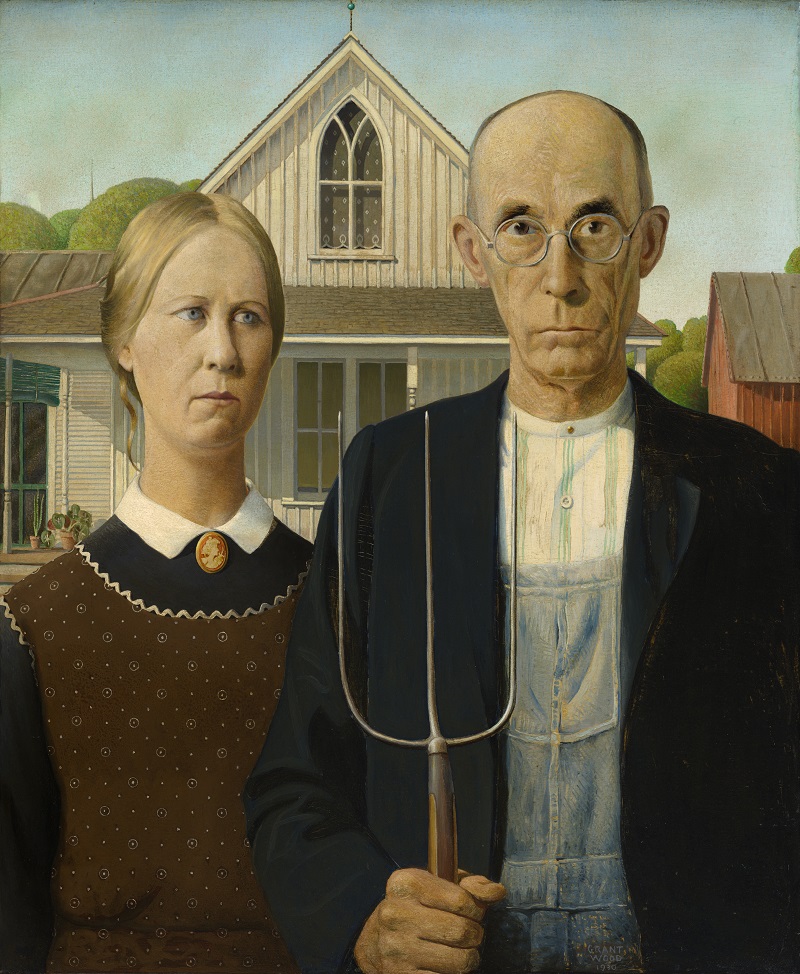

The star of the show, and a real coup for the Academy, is Grant Wood’s iconic American Gothic, 1930 (pictured above courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago), which was an instant hit when it was first shown and was immediately purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago (which has loaned about a quarter of the works in the show). Dubbed America’s Mona Lisa, the famous double portrait of an elderly farmer and his daughter (modelled by Grant’s sister and dentist) has never left North America until now; no doubt the Institute is having to cope with a deluge of disappointed visitors. The picture speaks to change – at a time of farm foreclosures and the young deserting rural homes for the lure of the city life and employment.

Just as illuminating is the show’s juxtaposition of two Edward Hopper paintings, revealing just what an exceptional figure Edward Hopper was in his time: his singular vision and “old masterly” style were poorly understood by contemporary critics. New York Movie, 1939, with its plush velvet, dimly lit, curtained interior exudes an overpowering sense of quiet desperation, while Gas, 1940 (pictured above, courtesy of Collection of Museum of Modern Art, New York), transfers the individual’s solitary internal world to the roadside location of a garish gas station at night. The searing red diagonal of pumps set against a never-ending stretch of road and dark forest creates a lingering feeling of disquiet. The exhibition concludes with a section “Looking to the Future”, featuring amongst other works Arthur Dove’s Swing Music (Louis Armstrong), painted in 1938, and an early Jackson Pollock (c.1938/41), both of which anticipate and usher in the Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s – this show would have been wonderfully paired with the Royal Academy’s recent Abstract Expressionism show in the main galleries. (Pictured above: Pollock's Untitlted, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago). Barter's simple thesis is that as America moved from the desolation and violence of the 1930s, through its 1941 entry into the Second World War and on to Cold War disillusionment and the notorious blacklisting of communist artists (most of the artists featured in America After the Fall were communists or had communist sympathies) – abstraction became not only a vibrant new territory for individual expression, but also the safest territory to explore.

The exhibition concludes with a section “Looking to the Future”, featuring amongst other works Arthur Dove’s Swing Music (Louis Armstrong), painted in 1938, and an early Jackson Pollock (c.1938/41), both of which anticipate and usher in the Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s – this show would have been wonderfully paired with the Royal Academy’s recent Abstract Expressionism show in the main galleries. (Pictured above: Pollock's Untitlted, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago). Barter's simple thesis is that as America moved from the desolation and violence of the 1930s, through its 1941 entry into the Second World War and on to Cold War disillusionment and the notorious blacklisting of communist artists (most of the artists featured in America After the Fall were communists or had communist sympathies) – abstraction became not only a vibrant new territory for individual expression, but also the safest territory to explore.

- America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s at the Royal Academy from 25 February to 4 June 2017

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment