David Lynch: The Art Life review - authentic and revealing | reviews, news & interviews

David Lynch: The Art Life review - authentic and revealing

David Lynch: The Art Life review - authentic and revealing

Candid doc charts Lynch's early years, and how his visual art morphed into film

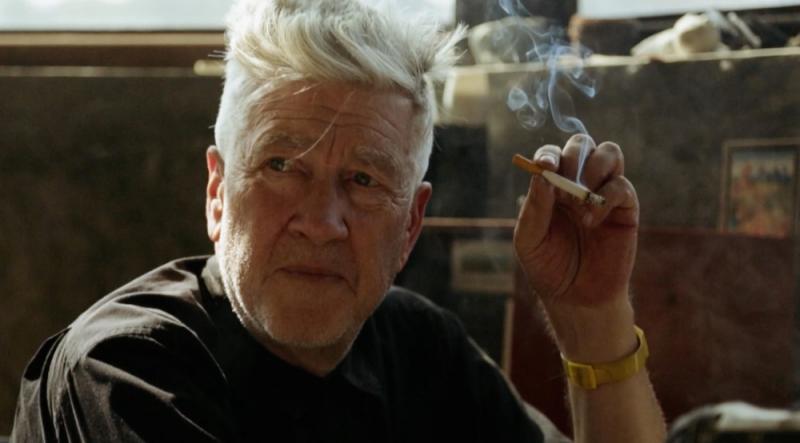

"You drink coffee, you smoke cigarettes, and you paint. And that’s it." So goes David Lynch’s memorable description of what he calls "the art life" in Jon Nguyen’s frank and engaging documentary. It’s a life that Lynch imagined himself living as a student and a young man – surrounded by the detritus of a disorderly studio, working all hours at his latest visual creation.

It’s this early period in Lynch’s creative life that’s the subject of Nguyen’s film, charting his childhood and student years as a driven, enthusiastic young artist, up to the creation of his movie Eraserhead in 1977, which would make his name as a film maker. David Lynch: The Art Life is virtually an autobiography, in fact. It’s told entirely through Lynch’s own voiceover – captured with deadpan frankness in a transparent recording booth, shots of which pepper the film – and uses a wealth of photos (pictured below) and home movie footage from the Lynch family. It feels spontaneous, off-the-cuff, but by the end it’s clear that this is a clearly structured, tightly argued tale. We hear Lynch on his childhood – one that begins in tremendous happiness and freedom, he says, with supportive parents and good friends, but one that starts to grow darker as he falls in with the wrong crowd at high school (he doesn’t elaborate much), then worries over how he’d deal with the diverging strands of his life if they ever intersected.

We hear Lynch on his childhood – one that begins in tremendous happiness and freedom, he says, with supportive parents and good friends, but one that starts to grow darker as he falls in with the wrong crowd at high school (he doesn’t elaborate much), then worries over how he’d deal with the diverging strands of his life if they ever intersected.

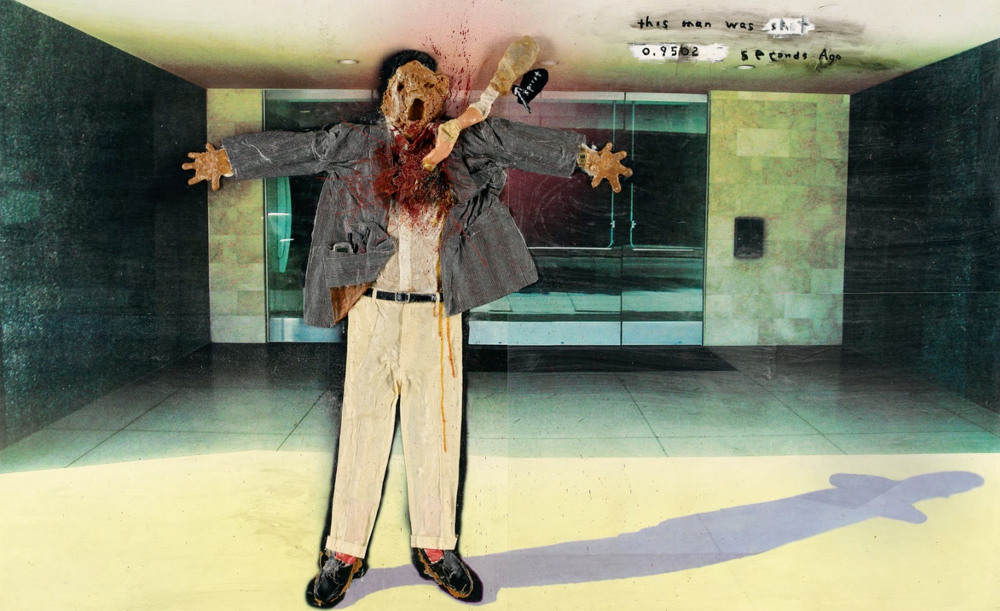

Running throughout, however, is Lynch’s evident passion for visual art, crystallised at a young age by his contact with artist Bushnell Keeler, the father of a school friend. And it feels like an entirely natural, authentic passion: Lynch is seemingly unable to explain its origins, although he follows his calling through his determination to have his own studio, his rocky relationships with art colleges, and the difficulties it causes him with his parents. His father even disowns him at one point, following a disagreement over what time the young Lynch is expected home from his studio, the argument only resolved by Keeler’s intervention. We get to see plenty of Lynch’s artworks (pictured above) – often shadowy, Bacon-like disfigured forms in unsettling landscapes, muttering obscenities, or reaching for something beyond their grasp. Or gnomic aphorisms scrawled in dirt. And plenty of Lynch himself at work, too, bending wires to form scratchy words, moulding eyeless faces from foam, tearing and ripping obsessively at his canvases.

We get to see plenty of Lynch’s artworks (pictured above) – often shadowy, Bacon-like disfigured forms in unsettling landscapes, muttering obscenities, or reaching for something beyond their grasp. Or gnomic aphorisms scrawled in dirt. And plenty of Lynch himself at work, too, bending wires to form scratchy words, moulding eyeless faces from foam, tearing and ripping obsessively at his canvases.

This is a compelling portrait of a determined, highly individual young man, and it offers plenty of fresh perspectives on Lynch’s unmistakable creative world that we’re familiar with today. Yet its underlying thesis – that his work today can trace its origins directly back to events and memories from his childhood – just seems a bit too simplistic at times. It’s admittedly kicked off by Lynch himself, who right at the film’s beginning muses that you can’t escape the influence of the past on current ideas, even if they’re ideas that feel new. But Nguyen seems intent on pointing up specific references too, which can sometimes border on the absurd. Lynch reminiscing about playing in a mud pool as one of his earliest memories is immediately followed by a sequence in which he’s smearing mud-coloured paint across a canvas. A story of being "trapped" in his apartment as a student, afraid to step into the outside world, makes more sense when followed by a painting clearly conveying the same situation.

More fascinating, however, are the darker, more mysterious memories from Lynch’s childhood that sound like they could have stepped straight out of one of his movies. The mysterious bloody-mouthed naked woman he watches walking down his road in the dead of night as a young child. The inexplicable, apocalyptic storm that accompanies his first day at school. The deranged woman who crawls on all fours around the yard of his Philadelphia student lodgings. Nguyen, perhaps wisely, leaves these images to work their dark magic alone, but they suggest, too, a more creative blurring of memory and imagination, or at least an early predisposition towards the uncanny and the unexplained.

Nguyen’s movie elegantly charts Lynch’s move from static visual works into cinema, too – how he imagined his painted works somehow moving, leading to early experiments mixing live action and animation, and eventually his early movies The Grandmother and Eraserhead.

There’s plenty more that could have been picked apart here. At times, you long for someone to challenge Lynch, or ask him to elaborate on his assertions. But as a candid portrait of one of the most singular artists working today, presented entirely in his own terms, David Lynch: The Art Life feels authentic, revealing and anything but contrived.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

theartsdesk Q&A: Idris Elba on playing a US President faced with a missile crisis in 'A House of Dynamite'

The star talks about Presidential decision-making when millions of lives are imperilled

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Urchin review - superb homeless drama

Frank Dillane gives a star-making turn in Harris Dickinson’s impressive directorial debut

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Mr Blake at Your Service review - John Malkovich in unlikely role as an English butler

Weird comedy directed by novelist Gilles Legardinier

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Add comment