Peter Hall: A Reminiscence | reviews, news & interviews

Peter Hall: A Reminiscence

Peter Hall: A Reminiscence

The colossus who founded the RSC and took the National to the Southbank is fondly remembered

Theatre artist, political agitator, cultural advocate: Sir Peter Hall was all these and more in a career that defies easy encapsulation beyond stating the obvious: we won’t see his like again any time soon. He helped shape my experience and understanding of the arts in this country, as I am sure he did for so many others.

As the founder of the Royal Shakespeare Company and the man who led the National Theatre from the Old Vic to the Southbank, Hall was embedded in the world of the subsidized sector for which he tirelessly fought. To this day, I well recall him standing on a table at a National Theatre press conference around the same time as the talk cited above to announce the closure of the then-Cottesloe auditorium in response to government cuts. As ever, Sir Peter coupled a potent political point with an innate sense of the theatrical.

Hall by no means inhabited a cossetted state-funded preserve: subsidy, as his numerous books make plain, was a constant battle, and enemies arose alongside the allies. And as an avid player who knew both the value and the importance of the marketplace, he had his share of flops – more often than not musicals (Via Galactica on Broadway, the National’s New York-aimed Jean Seberg back home) – as well as triumphs, the last across a heady array of writers ranging from Shakespeare and the classical canon to premieres by Beckett, Tennessee Williams, Ayckbourn, and Pinter. (Pictured above: John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson in No Man's Land. Photograph by Anthony Crickmay)

Hall by no means inhabited a cossetted state-funded preserve: subsidy, as his numerous books make plain, was a constant battle, and enemies arose alongside the allies. And as an avid player who knew both the value and the importance of the marketplace, he had his share of flops – more often than not musicals (Via Galactica on Broadway, the National’s New York-aimed Jean Seberg back home) – as well as triumphs, the last across a heady array of writers ranging from Shakespeare and the classical canon to premieres by Beckett, Tennessee Williams, Ayckbourn, and Pinter. (Pictured above: John Gielgud and Ralph Richardson in No Man's Land. Photograph by Anthony Crickmay)

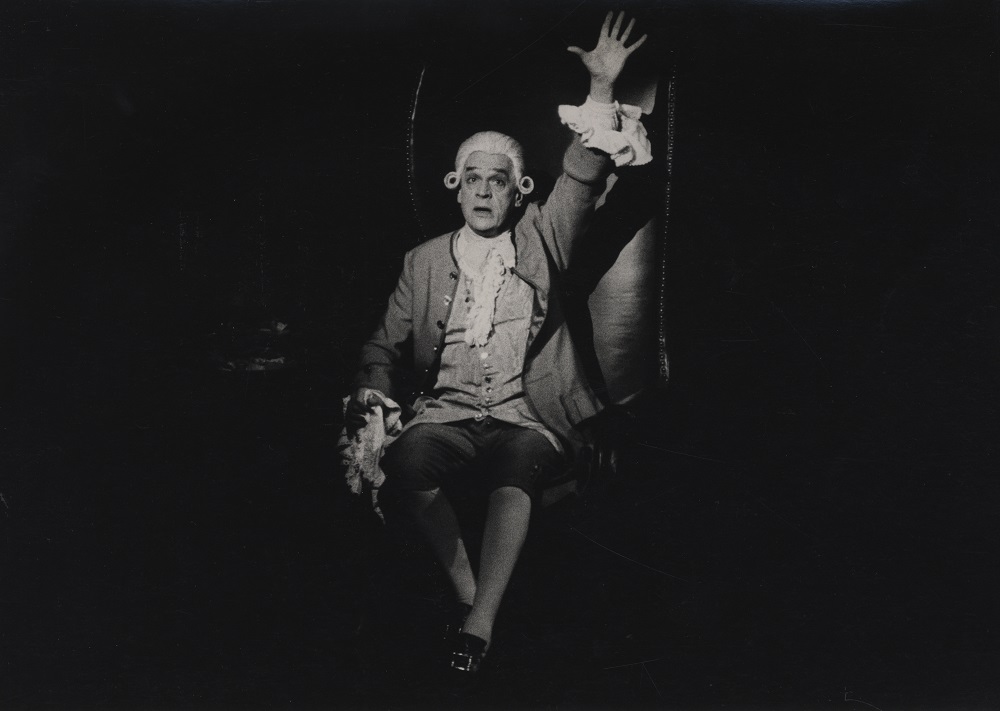

It’s been some while since New York’s Lincoln Center Theater mounted as brazenly audacious a mainstage premiere as John Guare’s fantastical Four Baboons Adoring the Sun, in 1992, directed by Hall and starring a radiant Stockard Channing: but there was Hall presiding over a press preview like the beneficent paterfamilias that, with six children and nine grandchildren, he actually was. The bravery paid off, netting Hall yet another in an ongoing series of Tony nominations. He twice won the prize, for The Homecoming (1967) and Amadeus (1981). (Pictured below: Paul Scofield in Amadeus. Photo by Nobby Clark)

Hall met my parents at that performance of Four Baboons and was conviviality incarnate, as he was in social occasions. Some years later, I found myself seated behind him and his devoted fourth wife, Nicki, at an Albert Hall Prom. “I see you’ve had a go at me,” he cheerfully remarked in response to a tepid review I had given one of his Peter Hall Company’s productions at the Playhouse Theatre down by the Embankment. But far from indulging in rancour, he soon moved on to sharing the happy news of his adored actress-daughter Rebecca’s latest career ascent, any blips on the timeline of his then-ceaseless output set against the weighty enormity of the whole. Journalists had their job to do, and so did he. As a theatre-mad university student, I savored every syllable of Hall’s Broadway premiere of Betrayal, notwithstanding Hall’s characteristically acute jab in his mesmerising Diaries some while later that Pinter-speak pretty well constituted a foreign language for his American cast – the scintillating Blythe Danner excepted. (The others were Raul Julia and Roy Scheider.) Once I moved to London, I was impressed with Hall’s devotion to the American repertoire, his towering Haymarket reappraisal of Orpheus Descending unleashing a primal fury in a Tennessee Williams text that had been sidelined up to that point. (That same production also brought Vanessa Redgrave back – after too many years in exile – to the New York stage, where she thereafter became a regular presence.)

As a theatre-mad university student, I savored every syllable of Hall’s Broadway premiere of Betrayal, notwithstanding Hall’s characteristically acute jab in his mesmerising Diaries some while later that Pinter-speak pretty well constituted a foreign language for his American cast – the scintillating Blythe Danner excepted. (The others were Raul Julia and Roy Scheider.) Once I moved to London, I was impressed with Hall’s devotion to the American repertoire, his towering Haymarket reappraisal of Orpheus Descending unleashing a primal fury in a Tennessee Williams text that had been sidelined up to that point. (That same production also brought Vanessa Redgrave back – after too many years in exile – to the New York stage, where she thereafter became a regular presence.)

Shakespeare, in turn, coursed through his veins with an affection equaled only by his love of Mozart, The Marriage of Figaro preeminently. (If theatre was Hall’s wife, opera was his mistress – not least a Salome, controversial in its day, in which his then-wife, Maria Ewing, appeared briefly in the nude.) A dozen or so years ago, I invited Hall to visit a class I was teaching on Twelfth Night to American undergraduates abroad. To my amazement, not only did he accept but he arrived on the day in peerless and thoroughly unpatronising form. Indeed, my one doubt at the time was how to temper so evident an enthusiasm that it wasn’t clear whether his fervent recitation of Orsino’s opening speech might not propel Hall to read for our benefit the entire play: his perpetual exaltation of the Bard was something to behold.

By the time Hall made his National Theatre swan song in 2011 with Twelfth Night, one noted a production that seemed to take the temperature of its director. Here was an autumnal, wintry view of a play, blessed with the presence as Viola of none other than daughter Rebecca (pictured left by Nobby Clark), capable of sunnier hues that had been consciously dampened down. In context, it seems no accident that Hall’s very last Shakespeare offering was a production in Bath that same summer of Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2. The Falstaffian Hall was sage enough to go out with a theatrical diptych that spoke to Hall’s own, unquenchable appetite, on the one hand, and to his clear-eyed awareness of the dying fall from which no one – not even Falstaff – is immune.

By the time Hall made his National Theatre swan song in 2011 with Twelfth Night, one noted a production that seemed to take the temperature of its director. Here was an autumnal, wintry view of a play, blessed with the presence as Viola of none other than daughter Rebecca (pictured left by Nobby Clark), capable of sunnier hues that had been consciously dampened down. In context, it seems no accident that Hall’s very last Shakespeare offering was a production in Bath that same summer of Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2. The Falstaffian Hall was sage enough to go out with a theatrical diptych that spoke to Hall’s own, unquenchable appetite, on the one hand, and to his clear-eyed awareness of the dying fall from which no one – not even Falstaff – is immune.

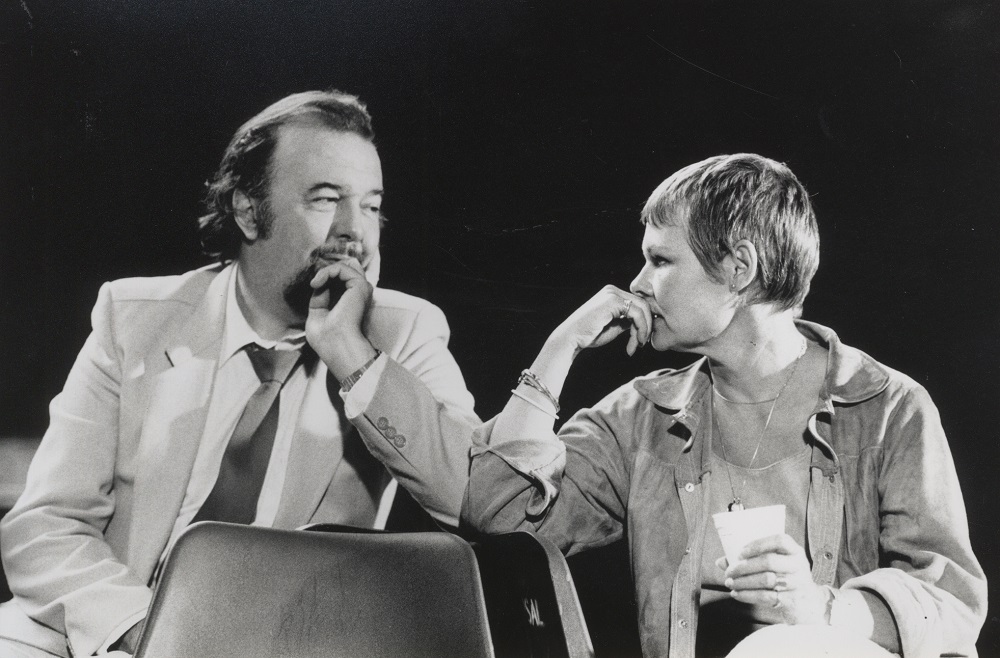

On that front, I shan’t forget encountering Hall during the interval of a 2008 Rose Theatre, Kingston, production of Love’s Labour’s Lost, starring Finbar Lynch, that was clearly still finding its footing. “All these years,” he said, a glint informing his pragmatism, “and I’m still trying to figure out how these plays work.” That Hall got it right as much and as often as he did would be legacy enough, the institutions to which he gave his life the additional bricks and mortar whereby his take-no-prisoners spirit was, as it were, made flesh. I treasure the numerous nine am phone interviews we had during my days as London theatre columnist for Variety when he and I would speak to discuss one or another hoped-for bit of casting, some likelier than others. (He never did get Madonna to play Maggie in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.) On form, few were as perceptive about the skills of others. “She’s got sex and wit, wit and sex,” Hall said by way of justifying his choice of Judi Dench as still the finest Cleopatra in many a generation. The actress had earlier on dismissed the job offer, arguing that she resembled a “menopausal dwarf”: Hall was having none of that, and the 1987 production marked a banner achievement all round. (Pictured above: Judi Dench with Peter Hall. Photo by Zoe Dominic)

I treasure the numerous nine am phone interviews we had during my days as London theatre columnist for Variety when he and I would speak to discuss one or another hoped-for bit of casting, some likelier than others. (He never did get Madonna to play Maggie in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.) On form, few were as perceptive about the skills of others. “She’s got sex and wit, wit and sex,” Hall said by way of justifying his choice of Judi Dench as still the finest Cleopatra in many a generation. The actress had earlier on dismissed the job offer, arguing that she resembled a “menopausal dwarf”: Hall was having none of that, and the 1987 production marked a banner achievement all round. (Pictured above: Judi Dench with Peter Hall. Photo by Zoe Dominic)

After he left the National and launched his Peter Hall Company, a moniker that survived across numerous producers and theatrical homes, I inquired at one point precisely who this company consisted of. The answer lay in the breadth of collaborators across a career spanning more than 60 years – in other words, the industry at large. We live nowadays in increasingly fragmented and scattered times, so when better to pause and acknowledge the inimitable colossus who for a while actually walked among us.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Add comment