Being Blacker, BBC Two review - absorbing film about family, culture and society | reviews, news & interviews

Being Blacker, BBC Two review - absorbing film about family, culture and society

Being Blacker, BBC Two review - absorbing film about family, culture and society

Molly Dineen documentary puts race identity in Brixton under the microscope

They don’t commission many television documentaries like Being Blacker (BBC Two) any more. That is not unconnected to the fact that Molly Dineen downed her camera a decade ago.

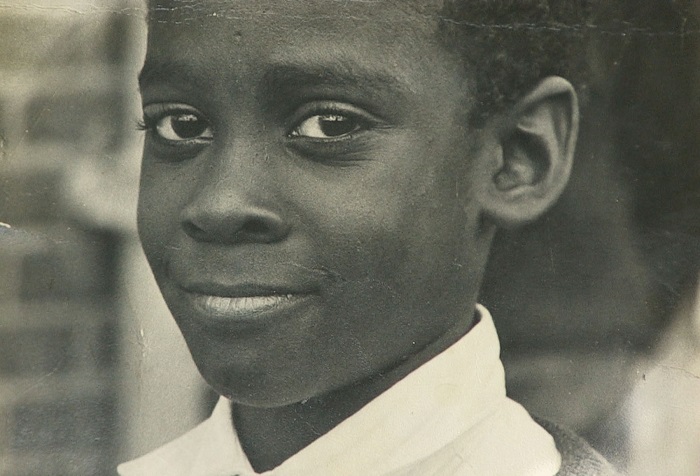

The title refers to Steve Burnett-Martin, better known in Brixton as Blacker Dread. He arrived in the UK from Jamaica as a boy (pictured below), where he was reunited with parents he barely knew. “‘Oo is dis woman?” he asked at the airport. In the narrative of his life, England didn’t want him. He was forced to retake his 11-plus as no one would believe he hadn’t cheated. Every day at grammar school in suburban Penge he ran the gauntlet of white kids whose goal was to beat him up. He couldn’t tell his parents for fear of upsetting their dream of a better life in England. He didn’t pass any exams. He got a Saturday job at Crystal Palace where racist fans would shout, “Oi nigger, come sell me a programme” or call him a “black cunt”. He remembers people telling him to “go up on the jam jar, you little gollywog”.

That was London in the 1970s. “You grow up feeling that you ain’t a part of what’s going on,” Blacker reasoned, “so you become what you would never have been.” Dineen encountered him in the 1980s while making a film about Jamaican sound systems in the UK. He found his niche as a record producer. The cause of their reunion, and the germ of this feature-length documentary, was the funeral of his mother Pauline (pictured below), which as a devoted son he asked Dineen to capture on film. She must have intuited that there was a longer story to be told when attending the funeral, alongside Pauline’s 94 grandchildren and great grandchildren. It lasted three and a half hours. Sure enough, it soon emerged the reggae record shop run by Blacker for more than 20 years, a symbol of old Brixton, was closing down because he was about to be sentenced for the white-collar crime of money laundering.

That was London in the 1970s. “You grow up feeling that you ain’t a part of what’s going on,” Blacker reasoned, “so you become what you would never have been.” Dineen encountered him in the 1980s while making a film about Jamaican sound systems in the UK. He found his niche as a record producer. The cause of their reunion, and the germ of this feature-length documentary, was the funeral of his mother Pauline (pictured below), which as a devoted son he asked Dineen to capture on film. She must have intuited that there was a longer story to be told when attending the funeral, alongside Pauline’s 94 grandchildren and great grandchildren. It lasted three and a half hours. Sure enough, it soon emerged the reggae record shop run by Blacker for more than 20 years, a symbol of old Brixton, was closing down because he was about to be sentenced for the white-collar crime of money laundering.

It was Blacker's first experience of prison. In that he differed from his childhood friend Brian, also known as Naptali. “You’d be a great getaway driver,” Dineen innocently told him when she first sat in his passenger seat. “I was!” he replied. before regretfully and honestly recalling his misspent youth as an armed robber, for which he’d spent 12 years behind bars. His record barred him from working as a chauffeur to help pay off sizeable arrears. Blacker’s son Solomon also fetched up in prison and, at 24, was shot dead the month he was released. His murder was never solved. There was moving DVD footage of the funeral at which Pauline prayed to God “that You let young men be at home where they belong”.

But where is home? The first half of the film explored Blacker’s vanishing world, the Brixton which is succumbing to rapid gentrification, before Blacker himself vanished into prison. Sentencing him in Croydon, the judge contemptuously dismissed this charismatic community totem as a "failure". In his absence Dineen flitted across to Jamaica to watch the progress of Blacker’s youngest son Jamehl, who had been seen as a troublemaker at school in London but was now getting top grades. After a year in prison, as soon as his tag came off, Blacker’s ambition was to return to the island from which he had been untimely ripped as a child. This was an absorbing film about family, culture and society, pieced together by Dineen as a character study with wider and deeper implications for the rest of us. It asked if, aside from the disappearance of openly racist language, anything much has changed since the 1970s, and if chances for Britain’s young black male population were any better. Blacker was particularly sceptical about the concept of diversity. “Diversity is a word. It doesn’t live, it doesn’t breathe.”

This was an absorbing film about family, culture and society, pieced together by Dineen as a character study with wider and deeper implications for the rest of us. It asked if, aside from the disappearance of openly racist language, anything much has changed since the 1970s, and if chances for Britain’s young black male population were any better. Blacker was particularly sceptical about the concept of diversity. “Diversity is a word. It doesn’t live, it doesn’t breathe.”

Towards the end, at a public vigil for yet another murdered boy, a young man gave a powerful speech about the need for the black community not to war with itself. "Us black boys especially we don’t value our other people," he said. "We’d rather go and fight, stab and shoot people and it’ s just for what?... We don’t know the value of this colour. We need to understand we got something important and valuable." And the gathered crowd broke into Bob Marley's "Redemption Song".

There were plenty of questions, fewer answers. Is it a problem that teachers in the UK are not allowed to use old-fashioned discipline of the kind welcomed by Jamehl (and his mother Maureen)? Why does prison contain a disproportionate number of Afro-Caribbean males? One thing Blacker wasn’t asked was how he came to have quite so many children, and by how many different mothers. Speaking at the wedding of one of them, he admitted to “about six” daughters - one of whom is a probation officer.

Blacker and Naptali were both wonderful show-offs who relished, and merited, the attention. “I’m talking for whoever’s the audience behind the camera,” said the latter. As Blacker uncapped his remarkable dreadlocks – his last haircut was when he was 14 – he shifted into patois, necessitating subtitles. It felt like something between an identity-conferring superpower and a defensive forcefield. “I don’t know if I’m academically wise,” he said. “I know I’m streetwise. I learnt my education from the ghetto college of further education. It’s called ghettology.” They don't make films like this any more, nor characters like him.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Add comment