theartsdesk Q&A: Hedvig Mollestad, Norway's bridge between heavy metal and jazz | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Hedvig Mollestad, Norway's bridge between heavy metal and jazz

theartsdesk Q&A: Hedvig Mollestad, Norway's bridge between heavy metal and jazz

The genre-busting guitarist talks about new album 'Smells Funny', a rotting eyeball and more

Norway’s Hedvig Mollestad Trio reset the dial to what jazz fusion sought to do when it emerged, and do so in such a way that it’s initially unclear whether they are a jazz-influenced heavy metal outfit or jazzers plunging feet-first

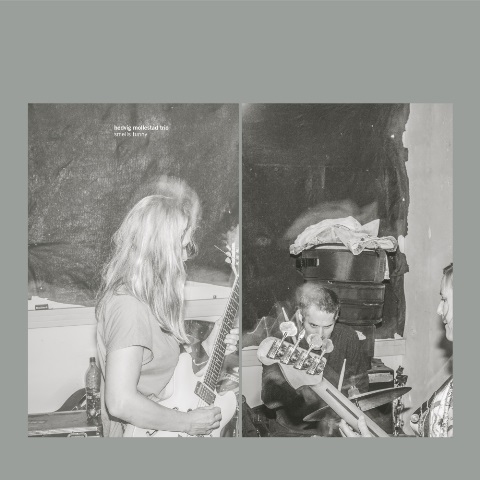

The trio is led by guitarist Hedvig Mollestad Thomassen. Ellen Breken plays electric and stand-up bass, and Ivar Loe Bjørnstad is on drums. All three are trained musicians with backgrounds in jazz. Despite this, there are no academic strictures to their live appearances. On stage, they hit audiences with full force and never let up. Mollestad does not stand still and often plays off, face-to-face, with Breken as Bjørnstad hammers his kit into the floor. On album, the power is caught by recording live in the studio. What is captured is thrillingly urgent and vital.

There are five studio albums by Hedvig Mollestad Trio. Smells Funny, the latest (pictured right), is released internationally this weekend. The first was 2011’s Shoot! Subsequent album titles All of Them Witches and Black Stabat Mater reveal much about the trio’s view of their music by acknowledging how it could be categorised. Yet, still, they are a jazz band rather than the black metal outfit the titles suggest.

There are five studio albums by Hedvig Mollestad Trio. Smells Funny, the latest (pictured right), is released internationally this weekend. The first was 2011’s Shoot! Subsequent album titles All of Them Witches and Black Stabat Mater reveal much about the trio’s view of their music by acknowledging how it could be categorised. Yet, still, they are a jazz band rather than the black metal outfit the titles suggest.

Smells Funny is their most cohesive album so far as its trade between the headlong rush into unstoppable riffing and improvisation is more adroitly balanced than ever before.

Before the release of Smells Funny, Hedvig Mollestad discussed the album, how the trio formulate their music and much more. In person, she is direct, engaging and warm. The conversation took place at the Oslo office of her label Rune Grammofon, during the week of the label’s 20th anniversary shows when Hedvig Mollestad Trio headlined Victoria, Norway’s national jazz venue.

KIERON TYLER: On Smells Funny, it sounds as if your guitar playing has changed slightly – less chordal and riffy, more with single notes taking the weight of each track. Has your guitar playing changed?

HEDVIG MOLLESTAD: I don’t know. You as a listener would be in better shape to evaluate that. You listen to the records. We play a lot so I don’t refer to the records and the evolution that happens in the recordings. In the studio we often do things before we do it live, so it might be very different live. I don’t know if it has changed, but it’s a normal thing that one’s playing changes with the years.

How much of your playing is instinctive? You can play very, very fast and hard. How much do you plot beforehand what you’re going to do?

How much of your playing is instinctive? You can play very, very fast and hard. How much do you plot beforehand what you’re going to do?

Tricky. When we are going to play a song – I call them songs – it’s supposed to be catchy for most of the melody or the riff but still you’re free to go away from it if you feel like it. You can go straight to it, do whatever you want but you can’t lose it totally. It’s the choice of the day. You have to make sure it’s nice to listen to. (Pictured above left and all shots below, on stage at Oslo's Victoria, December 1 2018)

How do Ellen and Ivar lock into that?

They also fly off. When we try to play these songs they change each time we play and to us it’s quite important that it is possible to change it, and that it’s a welcome impulse. Playing in a trio with a lot of improvisation we have to be working with the dynamic and also with the specificity of the performance to make it interesting and to be present in the music. It’s very rare that it is “supposed to be like this”. Parts are written but shouldn’t be played like that every time. The records aren’t a world apart because they are recorded live, but we have to decide how parts are going to be – “this part is so long.” We want a recordable version of the song. When we play it 30 times, we might change it as it won’t work live. What fits on record won’t always fit live. We don’t play all of our music live.

Do you jam?

Do you jam?

No. We very rarely do that. We play “these are the parts we have.” We play once, twice, then we stop and evaluate: say “change the measure to six beats instead of seven as it sounds too tricky. Let’s try that. The B part became a bit boring, let’s see what we can do to change that.” I don’t see that as jamming. On “Lucidness”, Smells Funny’s last track, it’s from short melodic themes that come at the end and the rest is improvised but it’s still an idea of the way to build and what kind of references in the music that we should link our hearts to. In that track it's Terje Rypdal, Miroslave Vitous and Jack DeJohnette’s Sunrise. I’m quoting Terje Rypdal way too much.

The writing credits – how are they split up?

It’s been different from record to record. The first one, I wrote most of the material but to a large and larger degree we agreed that if everybody contributes to the material we would reflect that. It’s very exciting to play something Ellen wrote as she’s very much a jazz head. When I play, I can’t play the way she made it. If she comes with a riff and says “it would be nice if you make something that would fit with this” or it could also be “these are the chords, could someone else make the melody?” The collaboration is so vital for the result. We spend a lot of time rehearsing.

You have some pretty odd song titles.

You have some pretty odd song titles.

Most of the time the titles come afterwards. They can sometimes be very childish. On the new album, “Beastie, Beastie” comes from the riff of “Sabotage” by The Beastie Boys. For “First Thing to Pop is the Eye” that’s from a nasty story a crazy driver told us in Finland. We stopped at gas station and he told us he’d been in a war in Lebanon and his friends were shot and that he had to lie there for days under their bodies. He said the first thing in the rotting process is for the eyes to pop, and he described the sound.

On stage, you dress specially – you put on a show

When I’m going to play a concert I always think it’s nice to dress up a bit. I want to show you I’m here, it’s a moment of live music and that this matters to me. It’s a mental change around. With the trio, it’s a fun thing to do as the other two are so much jeans and T-shirts off the stage. In the beginning we were standing very still and I wanted to move around more. We wanted to have something on stage that caught attention.

You’ve played live while pregnant. Very visibly so...

It’s just that you continue working in Norway until three weeks before your due date. There’s no reason not to, I was healthy. It was as natural to play with a child inside me as to play as a non-pregnant woman.

You’re a conservatory-trained musician...

You’re a conservatory-trained musician...

I don’t feel like that as there are so many more skilled jazz musicians. I went to university first so had taken a lot of basic subjects and left them out [at music school]. I played a lot at music school but did pedagogics. I didn’t think I was going to be a musician. Maybe I was a dropout.

You did different sorts of music before the trio...

Before the trio, I didn’t know what I was going to do. I liked to play guitar, enjoyed it very much. I wasn’t comfortable in all kinds of situations playing music. The first two years at the [music] academy, I had a guitar teacher who played a lot of bebop and it was very metrical and rhythmical. I had listened to a lot to bebop and liked it but I couldn’t handle the language. I always felt like an idiot in the class because it never sounded right. I was thinking at that time that if I didn’t find anything that fits I’d rather find something else. Then I got another teacher who had other ideas of phrasing and how to play chords. Also, a different idea of timing that worked so much more with me. Then I did something with the Trondheim Jazz Orchestra where the only way I could fit was by making sounds, playing chords or bebop guitar which didn’t sound right. I didn’t play with drums and [electric] bass until I was 20 or 21. When I was in high school I had played in bands with a double bass. Then when we started with the trio, we started playing standards which felt strange. We played Bill Evans tunes. We covered [proto-grunge band] The Melvins in the same set. We had some jazz club gigs on the west coast with a vocalist and the same thing happened where it just didn’t feel right. Then, around the end of 2009, we brought in our own material and started to play differently.

Did you ever think about singing?

Did you ever think about singing?

No. I was playing guitar.

People do both...

But people don’t do both. People play guitar without singing. I never thought I was going to be in instrumental trio. I wanted to play with bass and guitar – it was just that there was no one there singing. We never thought there would be a vocalist. We were going to play music.

What were you looking to in rock?

I didn’t really get acquainted with that kind of music until after my teens. I had heard Jimi Hendrix but I listened to his songs rather than his guitar work. I wasn’t this nerd: “what is he doing here?” I tried to play it, but in a very non-theoretical way. I listened to Paul McCartney’s Off the Ground, Janet Jackson, Richard Marx. I listened to mainstream jazz from the Fifties. My father was a trumpeter so we had a lot of Miles Davis and Coltrane too, Art Farmer. Easy, soft things. That was my world for a very long time. Then I met this girl who listened to grunge: Pearl Jam, Nirvana. I was offended by the logo of AC/DC – the lightning flash. I was a jazzy girl. They’re showing off.

Is there something Norwegian in that reaction? Frowning on shouting from the mountain tops?

We’re very good at not shouting from the mountain tops.

What does Norway think your music is? How is it categorised?

Who is Norway? The culture editors on the newspapers are very limited on the budget so there are very few places to have a profound coverage of music in Norway. They are very confused about it. When we talk about rock, it says absolutely nothing. What is rock? It’s like someone saying, “she’s the best guitarist.” That means nothing as you have to have a set of criteria for the music. So with rock and jazz, what is it? If we talk about genres, we should spend some time defining what it is within jazz that makes us agree we should call it jazz.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

Pop Will Eat Itself, O2 Institute, Birmingham review - Poppies are back on patrol

PWEI hit home turf and blow the place up

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

'Fevereaten' sees gothic punk-metallers Witch Fever revel in atmospheric paganist raging

Second album from heavy-riffing quartet expands sonically on their debut

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

theartsdesk Q&A: Soft Cell

Upon the untimely passing of Dave Ball we revisit our September 2018 Soft Cell interview

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Demi Lovato's ninth album, 'It's Not That Deep', goes for a frolic on the dancefloor

US pop icon's latest is full of unpretentious pop-club bangers

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Yazmin Lacey confirms her place in a vital soul movement with 'Teal Dreams'

Intimacy and rich poetry on UK soul star's second LP

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

Solar Eyes, Hare & Hounds, Birmingham review - local lads lay down some new tunes for a home crowd

Psychedelic indie dance music marinated in swirling dry ice

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

The Lemonheads' 'Love Chant' is a fine return to form

Evan Dando finally gets back in the saddle with an album of new tunes

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

Music Reissues Weekly: Evie Sands - I Can’t Let Go

Diligent, treasure-packed tribute to one of Sixties’ America’s great vocal stylists

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

'Deadbeat': Tame Impala's downbeat rave-inspired latest

Fifth album from Australian project grooves but falls flat

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

Heartbreak and soaring beauty on Chrissie Hynde & Pals' Duets Special

The great Pretender at her most romantic and on the form of her life

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

The Last Dinner Party's 'From the Pyre' is as enjoyable as it is over-the-top

Musically sophisticated five-piece ramp up the excesses but remain contagiously pop

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Moroccan Gnawa comes to Manhattan with 'Saha Gnawa'

Trance and tradition meet Afrofuturism in Manhattan

Add comment