Kader Attia / Diane Arbus, Hayward Gallery review - views from the margins | reviews, news & interviews

Kader Attia / Diane Arbus, Hayward Gallery review - views from the margins

Kader Attia / Diane Arbus, Hayward Gallery review - views from the margins

Two photographers explore colliding worlds

Feelings run high at the Hayward Gallery in a fascinating pairing of two artists from widely differing backgrounds. Kader Attia muses on unhappy, conflicted relationships between cultures in visual meditations on variations of colonialism.

Once criticised for what might appear as an obsession with freakery, it is increasingly evident how her curiosity was flavoured with sympathy and empathy. Attia is mesmerisingly obsessed with the difficulties of groups and societies, while Arbus focuses always on the individual or a tiny group united by personal relationships.

Kader Attia, b 1970, is a highly political French artist of Algerian background. He speaks in videos directly to the viewer, on a variety of topics exploring colonialism, influences and relationships – political, aesthetic, artistic – between colonisers and colonised, the powerful and the less so, sometimes in surprising ways. He has photographed marginal groups in their interactions with others, from clients to audiences: one wall is taken up with photographs of transgender Algerian sex workers working in Paris (main picture). Although the visitor is warned they might be shocking, the photographs are curiously decorous especially if – say – the rawness of Nan Goldin’s photographic explorations come to mind.

Kader Attia, b 1970, is a highly political French artist of Algerian background. He speaks in videos directly to the viewer, on a variety of topics exploring colonialism, influences and relationships – political, aesthetic, artistic – between colonisers and colonised, the powerful and the less so, sometimes in surprising ways. He has photographed marginal groups in their interactions with others, from clients to audiences: one wall is taken up with photographs of transgender Algerian sex workers working in Paris (main picture). Although the visitor is warned they might be shocking, the photographs are curiously decorous especially if – say – the rawness of Nan Goldin’s photographic explorations come to mind.

Elsewhere, free-standing vitrines and wall cases house wooden carvings of mutilated faces – facial self-mutilation has often been part of understood tribal rituals.These sculptures, which are disconcertingly handsome, are purposefully mixed with African antiquities, stuffed animals, found objects, and work by others that the artist has collected and apparently worked on. He implicitly questions how we display the material evidence of culture, and it would be fascinating to see him within the context of the British Museum and a different kind of audience. It is an exhibition to witness, read and watch: there are hours of videos.

Attia forces you to take time, and perhaps in this most Euro-centric of contexts begin to intuit something of the gaps between western and non-western modes of thinking and being. Educated at the finest of French art schools, Attia himself can talk the talk.

Diane Arbus (1923-1971) came from a rich mercantile New York family. Inward-looking in some respects, she also managed to engage with people – she saw the extraordinary in the ordinary, she empathised with those living on the margins, she found not only individuals but families. She was to leave an enormous corpus of work, photographs of those she had encountered or sought out in all sorts of milieux, from the streets of the city to their homes. She was as visible to her subjects as they to her, engaging with them rather than just invisibly capturing them in a moment. There was no decisive moment here: her subjects were posed, aware of her gaze, and they looked right back. She has been memorialised in major international exhibitions, publications and several biographies. This show, with her images of people set out on column after column, so that you walk among what may be characterised by that famous American phrase "the lonely crowd", is from the huge gift of her work made by her daughters to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the 100 or so photographs on show include 50 not seen before. It emphasises what it calls her beginnings, but she was no youngster; these date from 1956 to 1962, and are shot using 35mm film and a Nikon camera before she moved on to her better-known and larger square format using a Rolleiflex.

Although Arbus was obviously not a war photographer, she has a quality shared by Don McCullin; her subjects, almost always aware of her camera, are granted not only their autonomy but their dignity. They are consenting adults – and children – not snapped all unknowing. She famously said that she believed there were things nobody would see if she had not photographed them: fundamentally, she showed a vast human spectrum of individuals and groups, which were conventionally invisible except to their own: from transgender people to strippers, nudists, swingers, the disabled (both physically and mentally) and freaks. But she also captured the emotions of ordinary family groups, affectionate couples, children.

Although Arbus was obviously not a war photographer, she has a quality shared by Don McCullin; her subjects, almost always aware of her camera, are granted not only their autonomy but their dignity. They are consenting adults – and children – not snapped all unknowing. She famously said that she believed there were things nobody would see if she had not photographed them: fundamentally, she showed a vast human spectrum of individuals and groups, which were conventionally invisible except to their own: from transgender people to strippers, nudists, swingers, the disabled (both physically and mentally) and freaks. But she also captured the emotions of ordinary family groups, affectionate couples, children.

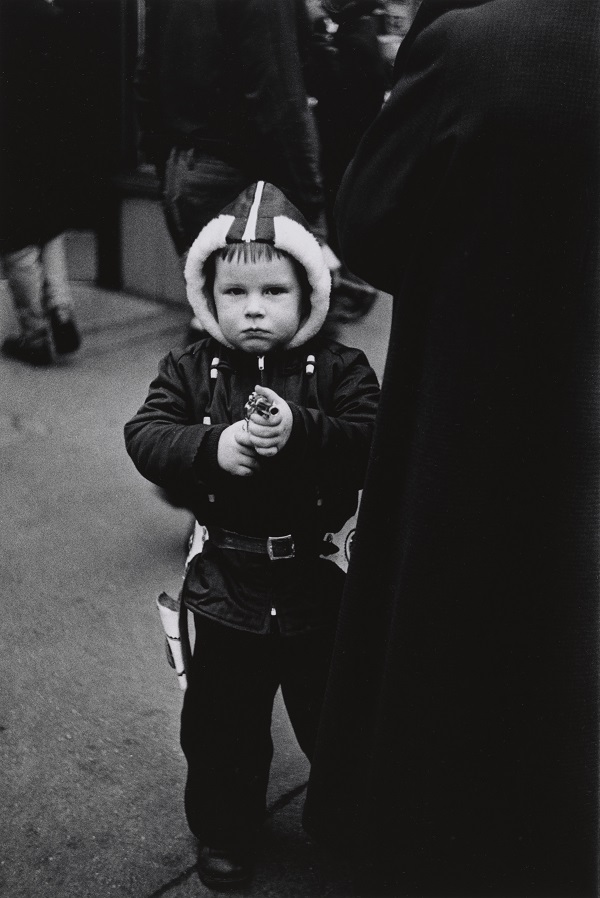

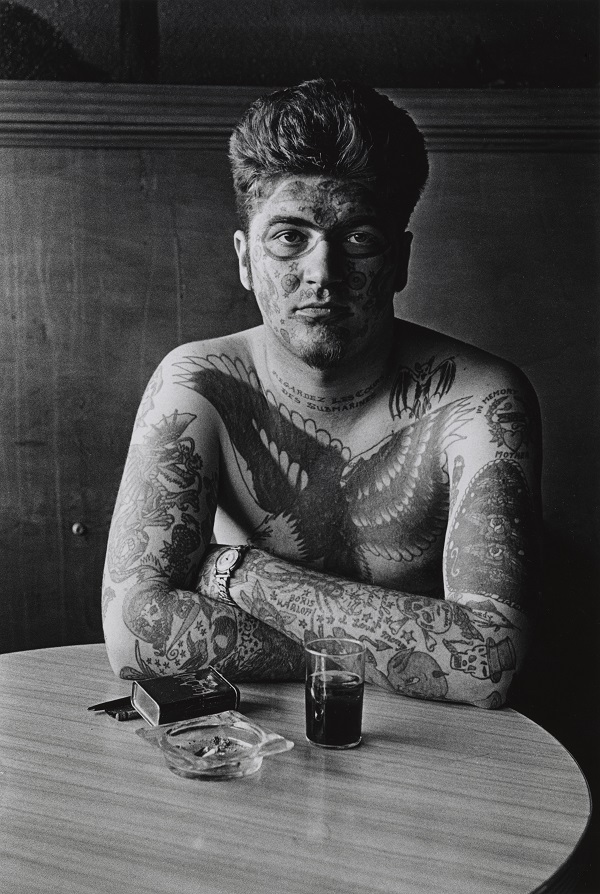

All is in black and white, thus exhibiting total control of the process of developing. The titles tell us what we see: Clown in a Fedora, Lady on a Bus, Couple Arguing, The Human Pincushion, Stripper with Bare Breasts. Here is the boy with a toy gun (pictured above right), the heavily tattooed Jack Dracula at a bar (pictured above left), a Russian lady midget in her kitchen. We look down on a table bearing a terrifying, partially dissected male corpse, his receding hairline visible, an identifying tag on his right foot. The images are often slightly blurred, and range from the profoundly disturbing to the totally odd, the ingratiating and even the surprisingly charming. We can make up the stories, and her work at a time when art photography was barely viable is her extraordinary legacy, her imagery changing the ways in which we view the interplay of society and individuals. This enthralling display shows us Arbus becoming Arbus.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment