Don McCullin, Tate Britain review - beastliness made beautiful | reviews, news & interviews

Don McCullin, Tate Britain review - beastliness made beautiful

Don McCullin, Tate Britain review - beastliness made beautiful

The darkest, most compelling exhibition you are ever likely to see

I interviewed Don McCullin in 1983 and the encounter felt like peering into a deep well of darkness. The previous year he’d been in Beirut photographing the atrocities carried out by people on both sides of the civil war and his impeccably composed pictures were being published as a book.

Some of these photographs are included in Tate Britain’s survey of his 60-year career, one of the darkest but most compelling exhibitions you are ever likely to see. There’s the group of young musicians approaching the body of a Palestinian girl lying prone in a bombed out street – celebrating her death in song. There’s mayhem in the Dar al Ajaza Islamia Hospital where, traumatised by the bombing, psychiatric patients mill about distractedly or lie screaming on the rubble-strewn floor. At the centre of the picture is a woman carrying a deformed child; she looks as if she is dancing to the rhythm of the guns. Many of the scenes are so appalling that they feel surreal; reason has been ousted by lunacy.

McCullin’s career as a photojournalist began almost by accident in 1958 with a photograph of a group of lads he’d been at school with, posing in a bombed-out building in Finsbury Park (pictured below left). A few months later “the Guvnors”, as the gang was called, were implicated in the murder of a policeman and McCullin’s photo was published in the Observer.

Over the next 40 years, he was sent on assignment by the Observer and the Sunday Times to cover conflicts in Cyprus, the Congo, Biafra, Vietnam, Cambodia, Northern Ireland, Iran and Iraq and the monstrous things he witnessed took their toll. “I feel as if I’ve got an incurable disease,” he told me in 1983. “I ought to be in that madhouse in Beirut – that’s where I belong. I used to find war exciting, now I go in there like a machine. I’m a newspaper man and I’m assigned to cover it. But I’ve also got the nerve to do it – to go to the edge – it’s the thing I do best.”

Over the next 40 years, he was sent on assignment by the Observer and the Sunday Times to cover conflicts in Cyprus, the Congo, Biafra, Vietnam, Cambodia, Northern Ireland, Iran and Iraq and the monstrous things he witnessed took their toll. “I feel as if I’ve got an incurable disease,” he told me in 1983. “I ought to be in that madhouse in Beirut – that’s where I belong. I used to find war exciting, now I go in there like a machine. I’m a newspaper man and I’m assigned to cover it. But I’ve also got the nerve to do it – to go to the edge – it’s the thing I do best.”

And he is undoubtedly the best. What singles him out his refusal to glamorise war and his determination to show its effects not just on hapless civilians caught in the crossfire, but on the soldiers themselves. In his pictures there are no heroes, just people trapped in what he describes as “the worst possible kind of living theatre”.

Despite frequently being in the thick of it, McCullin has taken surprisingly few shots of action. Most notable is the US marine hurling a grenade into the air during the battle for Hue, in Vietnam in 1968 (main picture). His dynamic silhouette is framed by vertical posts, all that’s left of the local houses. “He looked like an Olympic javelin thrower,” recalls McCullin. “Five minutes later this man’s throwing hand was like a stumpy cauliflower; completely deformed by the impact of a bullet.”

Images like these are so memorable they’ve become part of the archive imprinted on our minds. A US marine stares blankly into space, so numbed by shell shock that he looks as immobile as a bronze statue; then there’s the North Vietnamese soldier lying dead among a slew of bullets and photos of the wife and children he’ll never see again.

The pictures that haunt me the most are of starving Biafrans – the infant desperately suckling the withered breast of its emaciated mother and the skeletal albino boy scarcely able to stand on his stick-like legs. Their impact comes from the empathy they arouse, but McCullin is also able to tell a story just through brilliant composition. Taken on his first assignment, in Cyprus in 1964, is the shot of a gunman running from a dark doorway along a sunlit street in Limassol. Cast onto the wall in front of him, his shadow seems to propel him towards to his destiny. Seven years later, In Northern Ireland, comes another pavement dash; a posse of hyped-up British soldiers charges along a Londonderry street sending a horrified woman shrinking into a doorway.

The pictures that haunt me the most are of starving Biafrans – the infant desperately suckling the withered breast of its emaciated mother and the skeletal albino boy scarcely able to stand on his stick-like legs. Their impact comes from the empathy they arouse, but McCullin is also able to tell a story just through brilliant composition. Taken on his first assignment, in Cyprus in 1964, is the shot of a gunman running from a dark doorway along a sunlit street in Limassol. Cast onto the wall in front of him, his shadow seems to propel him towards to his destiny. Seven years later, In Northern Ireland, comes another pavement dash; a posse of hyped-up British soldiers charges along a Londonderry street sending a horrified woman shrinking into a doorway.

Seeing these photographs displayed in a museum context, many years after the events they record, encourages one to view them as artworks that bear dispassionate witness to the barbarity of men (always men). “Looking at what others cannot bear to see,” McCullin has said, “is what my life as a war reporter is all about.”

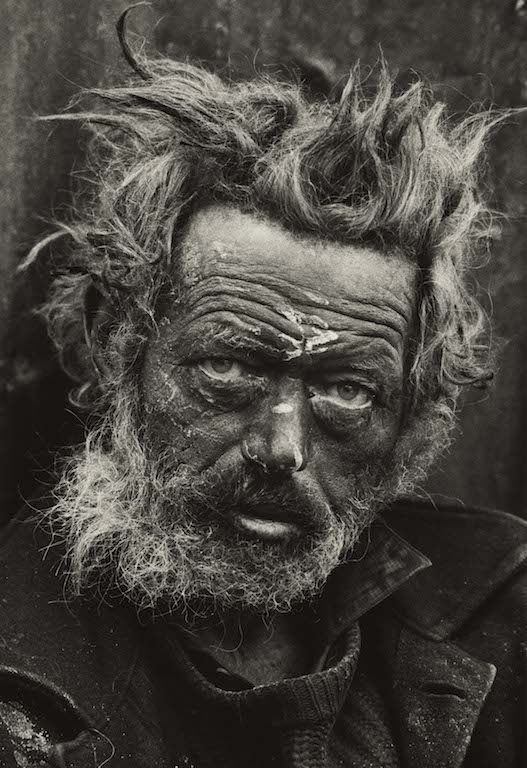

One also becomes acutely aware of the darkness saturating the images. McCullin spends hours in the darkroom revisiting his pictures; he printed most of the 250 photographs on show, so you can be sure that the rich blacks and sombre mid tones are intentional. Darkness attracts him more and more, it seems. When not on assignment abroad, he sought out the destitute, mad and disaffected back home. With his wild hair and dirt-encrusted face, the homeless Irishman he befriended in Spitalfields in 1970 (pictured above right) looks as traumatised as that shell-shocked marine, while the man sleeping on a filthy pavement nearby seems as lifeless as the corpse of that Viet Cong soldier.

In Sunderland he photographed the unemployed scrabbling for coal; in Bradford he recorded the squalid conditions in which young and old were forced to live, and in West Hartlepool he followed a man walking to work as the dawn light struggled to dispel the clouds of smoke belching from the steel work chimneys.  McCullin has lived in Somerset for 30 years and photographs the surrounding landscape on dank winter days when heavy mist softens the contours (pictured above) or threatening clouds fill the sky with drama. And he still visits war zones. His photograph of Homs, the town where war reporter, Marie Colvin was killed by Assad’s bombs, records the utter devastation wreaked by Syrian forces. Recently he has been documenting remnants of the Roman Empire, such as the theatre at Palmyra after it was decimated by Islamic State fighters. Emblems of man’s hubris, spite and folly, ruins are an obvious choice for someone who has seen too much of all three.

McCullin has lived in Somerset for 30 years and photographs the surrounding landscape on dank winter days when heavy mist softens the contours (pictured above) or threatening clouds fill the sky with drama. And he still visits war zones. His photograph of Homs, the town where war reporter, Marie Colvin was killed by Assad’s bombs, records the utter devastation wreaked by Syrian forces. Recently he has been documenting remnants of the Roman Empire, such as the theatre at Palmyra after it was decimated by Islamic State fighters. Emblems of man’s hubris, spite and folly, ruins are an obvious choice for someone who has seen too much of all three.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good