Don McCullin: Looking for England, BBC Four review - a hard look at home | reviews, news & interviews

Don McCullin: Looking for England, BBC Four review - a hard look at home

Don McCullin: Looking for England, BBC Four review - a hard look at home

Class, conflict, comedy, charm: the great photographer rediscovers his native land

A picture is worth more than a thousand words, never more so than with the photographs of Don McCullin. The octogenarian photographer’s black-and-white imagery made the Sunday Times colour supplement the talk of international media in the 1970s.

In the course of this focused journey, he told us his advice to want-to-be war photographers is that you can photograph war at home. He hated being called a war photographer, and wanted just to be called a photographer. England is close to his heart and he is consciously, poignantly coming to the end of his own journey, as he subtly reminded both himself and us in the course of these domestic travels.

His English journey was a choppy one, each group and place discrete and distinct. Punctuation of a sort was provided by the filming on location in colour; by McCullin’s own photographs, always in black and white; and by the visits to his darkroom at home, bathed in the necessary red light, as he looked at contact sheets (pictured below, by Eoin McLoughlinn) and developed his negatives (lower picture, by Adrian Sibley). It seemed almost womblike, a real shelter, even a sanctuary; he told us how crucial his darkroom time – four or five hours a day when working – was to his well-being. All done by hand, eye and analogue camera: the inadequacy of digital to his practice made explicit. McCullin has always been class-conscious, growing up poor in gangland Finsbury Park. Appropriately then, he started looking for England in Glyndebourne. He changed with a rather endearing clumsiness to formal wear, and sallied forth. He was painstakingly polite to his human subjects, always asking permission to photograph, and engaging in brief social exchanges. But at Glyndebourne he could, quite understandably, not avoid caricature.

McCullin has always been class-conscious, growing up poor in gangland Finsbury Park. Appropriately then, he started looking for England in Glyndebourne. He changed with a rather endearing clumsiness to formal wear, and sallied forth. He was painstakingly polite to his human subjects, always asking permission to photograph, and engaging in brief social exchanges. But at Glyndebourne he could, quite understandably, not avoid caricature.

In Eastbourne, under grey skies, gusts of wind and eventually torrential rain, McCullin was charmingly delighted at the sheer absurdity of the English sea-side holiday. He thought of Monty Python when watching the gallantry of the musicians ensconced in the rain in the bandstand, and their ancient audience. One man, neatly photographed, sat in the wind on the pier eating his fish-and-chips lunch out of a paper bag, delighted by the fresh air as he was cooped up for the rest of the day in his job as a hotel manager.

McCullin’s own energy was set against his implacable pessimism

He went down memory lane as he visited his childhood home in Finsbury Park, the area now very much on the up and up, and recollected his first memorable photograph of the besuited bad boys of the local gang posed by McCullin in a derelict building, his first-ever sale, to the Observer in 1958. But the visit was shaded by sadness: his father had died when he was only 40, his son Don at only 13, a loss still raw. Although McCulllin, in a rare moment of introspection, acknowledged the spur that pain gave him to try to achieve something.

Then back to the East End where the contrast between the poorest living next to the richest, those in the City, still irritated McCullin. A curiously jovial homeless man with a broken ankle, Conroy Rhoden, was to be found on the street in the East End, armed only with a faith in God. Photographed with permission, each subject is named, individuality honoured, dignity intact – unless the subject, so to speak scarpers, as did a druggie young mother, her face already permanently scarred by neglect and abuse. The affection for the world of the East End was palpable, but the pessimism shone through, too: several times the theme of how increasingly bad things were in England, one of the world’s richest countries, emerged, with the nation never more divided than now. McCullin’s own energy was set against his implacable pessimism, which in turn was contrasted to his ability to find sheer enjoyment in ritualistic set pieces. We wandered from Goodwood 1960s nostalgia to the hunt setting out in Church Farm in Wiltshire, with a surprisingly sinister moment there as masked saboteurs followed the horses and hounds.

The affection for the world of the East End was palpable, but the pessimism shone through, too: several times the theme of how increasingly bad things were in England, one of the world’s richest countries, emerged, with the nation never more divided than now. McCullin’s own energy was set against his implacable pessimism, which in turn was contrasted to his ability to find sheer enjoyment in ritualistic set pieces. We wandered from Goodwood 1960s nostalgia to the hunt setting out in Church Farm in Wiltshire, with a surprisingly sinister moment there as masked saboteurs followed the horses and hounds.

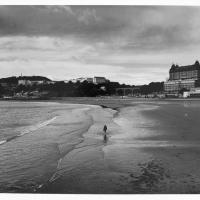

And finally out of the Home Counties, to places McCullin has held in his highest esteem for decades. First to Bradford, where everything was and is of interest, once the home to a large Jewish community, now with a major Muslim religious festival in its streets, complete with ceremonial horse and half-naked men beating their chests, where once he had photographed a woman and child in a rat-infested hovel. Then on to Consett in County Durham, destroyed with the disappearance of the steel industry, its traces subsumed now in suburbia. And lastly, island nation once more, to Scarborough, where a middle-aged man came up to tell the photographer that he was one of the boy footballers playing on the beach captured in an image 47 years ago: McCullin thanked him for being the subject for a photograph that had been eminently saleable.

McCullin told us several times he had used photography to find himself. The great strength of his English peregrinations, though, were not his remarks, often blunt, sometimes curiously naïve, but the revelatory images of individual people in a myriad of different social classes and places. Through his gaze, disillusioned, sad, sharp and affectionate, he showed us for good and ill his England of today.

Below: gallery from 'Looking for England', click on image to open

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Mr Scorsese, Apple TV review - perfectly pitched documentary series with fascinating insights

Rebecca Miller musters a stellar roster of articulate talking heads for this thorough portrait

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

Down Cemetery Road, Apple TV review - wit, grit and a twisty plot, plus Emma Thompson on top form

Mick Herron's female private investigator gets a stellar adaptation

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Add comment