My Enemy's Cherry Tree: Wang Ting-Kuo review - a masterpiece from Taiwan | reviews, news & interviews

My Enemy's Cherry Tree: Wang Ting-Kuo review - a masterpiece from Taiwan

My Enemy's Cherry Tree: Wang Ting-Kuo review - a masterpiece from Taiwan

A tense story of love doomed by power

Early every evening, Miss Baixiu comes to sit in an isolated café. She is the daughter of Luo Yiming, the respected employee of a successful commercial bank in charge of loans throughout central Taiwan. As a rich man, an aesthete and a philanthropist he enjoys status, power, acclaim.

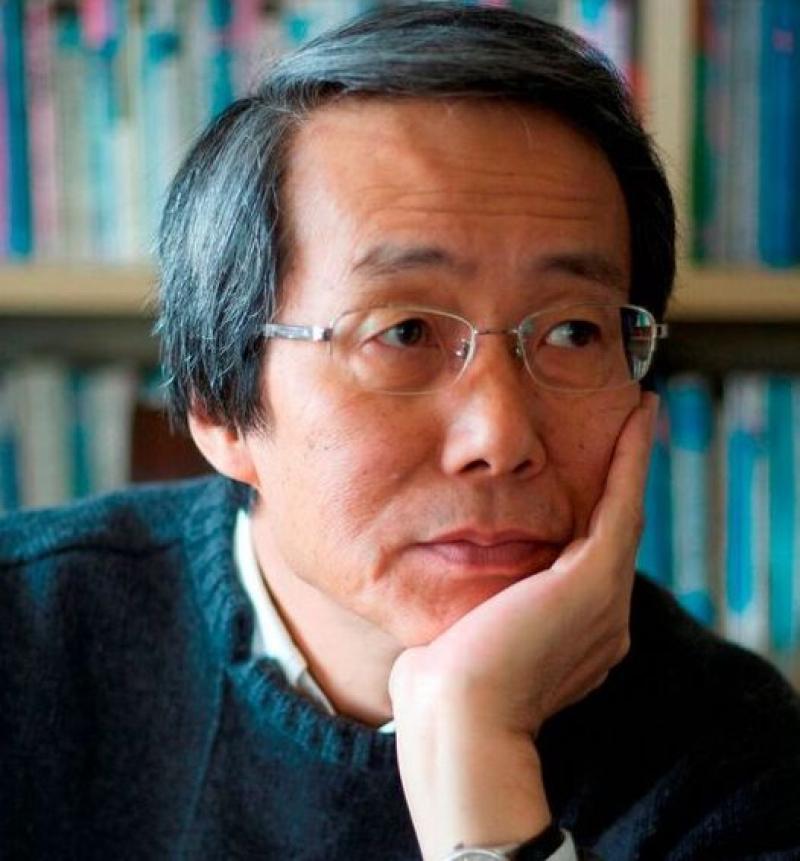

So begins Wang Ting-Kuo’s searing indictment of the insidious effect of power imbalances between people, told through a doomed love story. The subject is close to Wang’s heart. As a promising young author he was compelled by his future wife’s father to give up writing or risk losing her and in My Enemy’s Cherry Tree, the effect of power is felt in many ways. Differences in social standing, wealth and upbringing carve gulfs between characters and throw relationships and exchanges into sharp relief. Born to poor parents, our narrator grows to be relatively at ease with his bombastic “unpretentious and rough-hewn” property developer boss, Boss Motor, while he treats with reserve the meticulous and image-conscious Luo who gives Qiuzi free photography lessons and whom he imagines standing at her elbow, murmuring how to frame each shot.

As becomes clear though, he’s not innocent either. His and Qiuzi’s relationship is not without its own particular dynamic which, in the course of his tale, prompts anguished soul searching. Drawn together in part by common, hard upbringings, he describes her as “almost like my second self.” He is tender, seeking out an instrument that makes rain sounds to soothe her after an earthquake resuscitates old, perturbing demons; he notices and cherishes small, ingenuous things – like how “the hint of a smile would dance around her lips when I was only partway through telling her something”. Yet in quiet, unconscious ways, her life is subjugated to his. His work takes him away for weeks at a time and her naïvety (or acceptance) of this is devastating. Flicking through the photos she proudly shows him, he is struck by how the camera, far from expanding her horizons, “had actually exposed the narrow confines of our life.”

As becomes clear though, he’s not innocent either. His and Qiuzi’s relationship is not without its own particular dynamic which, in the course of his tale, prompts anguished soul searching. Drawn together in part by common, hard upbringings, he describes her as “almost like my second self.” He is tender, seeking out an instrument that makes rain sounds to soothe her after an earthquake resuscitates old, perturbing demons; he notices and cherishes small, ingenuous things – like how “the hint of a smile would dance around her lips when I was only partway through telling her something”. Yet in quiet, unconscious ways, her life is subjugated to his. His work takes him away for weeks at a time and her naïvety (or acceptance) of this is devastating. Flicking through the photos she proudly shows him, he is struck by how the camera, far from expanding her horizons, “had actually exposed the narrow confines of our life.”

It’s not just people who exert influence on their lives – the young couple seem to be tyrannised by objects. Not for their materiality (through cost is a frequent barrier) but for what they lead to, what they imply. There’s the unassuming, bird-like kettle they buy which wins Qiuzi the camera that leads them to the Luo household. There’s the smell of leather in a Cadillac which to our narrator is “the lure of money and power, mysterious, enticing and yet out of reach.” There’s the development project on the mountain which keeps them apart and lures them into seeking a loan for which they have no collateral. The cumulative sense is of things that happen to them. The couple's one certain choice is having chosen each other but even devotion becomes a trap.

Wang’s prose is both perspicacious and dream-like, psychologically probing and rich in detail. The son of a janitor, our narrator becomes a naïve army discharge who accidentally joins the Shell-less Snail protest against rocketing house prices in Taipei. Yet soon enough he is selling an apartment to a lady who sells street dumplings and managing housing developments. Wang’s handling of these ironies is deft, the hobbled mentality of a man from a poor background is figured with sensitivity. His imagery – beautifully translated by Howard Goldblatt and Sylvia Li-chun Lin – is striking. Qiuzi’s hair “was never longer than chin length, layered to a tapering end, like a fox gazing at snow on the nape of her neck”; a room “had a very low ceiling and was carpeted in red from one end to the other, as if it was floating on the surface of the sea”; Qiuzi’s provocative, mischievous smile makes her look “as if she’d been sucking on a preserved plum.”

This is a lush, tense and devastating novel (his English debut) from a Taiwanese master of style and form.

- My Enemy's Cherry Tree by Wang Ting-Kuo is published by Granta (£12.99 paperback)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Add comment