Almost exactly a century after the Weimar Republic’s constitution took effect, English Touring Opera presents a show whose birth coincided with the Republic's untimely death. His third collaboration with the prolific, maverick playwright Georg Kaiser, Kurt Weill’s The Silver Lake (Der Silbersee) opened in three German cities (Leipzig, Magdeburg and Erfurt) just 19 days after Hitler had come to power in 1933. Although it lacks much of the acid topicality and mischief that marks Weill’s partnerships with Bertolt Brecht, that did not stop the newly-empowered Nazis from swiftly closing the productions down. They then incinerated the score during the book-burnings of 10 May 1933. Weill himself fled the nascent dictatorship for America soon after the premiere.

The Silver Lake comes to Hackney Empire, with a national tour to follow, as a rare and precious glimpse of the sort of ambitious, multilayered music-drama – Weill, inspired by Mozart’s The Magic Flute, thought of it as a Singspiel – that the progressive Weimar stage could host on the eve of its total annihilation. Even if this brooding and sombre “winter’s tale” lacks the crowd-pleasing cheek and bite of The Threepenny Opera or the tawdry showbiz splendours of The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, all praise to ETO and its resourceful team and cast for reviving it to shed light from the past on our own conflicted times. The Silver Lake begins in satire and ends in symbolism. It follows the fate of a jobless worker, Severin, his entanglement with the conscience-stricken policeman who shoots and injures him, Olim, and their final journey towards a reconciliation that has both political and mystical dimensions (pictured above, David Webb as Severin and Ronald Samm as Olim). This version, directed by James Conway and conducted by James Holmes, radically slims down Kaiser’s dialogue and so tilts the balance of the work towards, if not full-blown opera, then at least the classic Singspiel. (ETO are playing it alongside another such hybrid, Mozart’s The Seraglio). The shadow of Weill’s recent sidekick Brecht falls across the production in many ways, not least in the alternation of English for the spoken dialogue and German for most of the sung numbers (except for the Chorus, who deliver their warnings and admonitions in English). In case this dose of Verfremdungseffekt doesn’t do the trick of keeping us alert, the translated lyrics for the songs sometimes appear on screens, sometimes scrawled on placards, inscribed on scrolls or even spooled on spindles that unfurl the text across the stage. Alienated? I’m afraid I was: a bright idea has got confusingly out of hand.

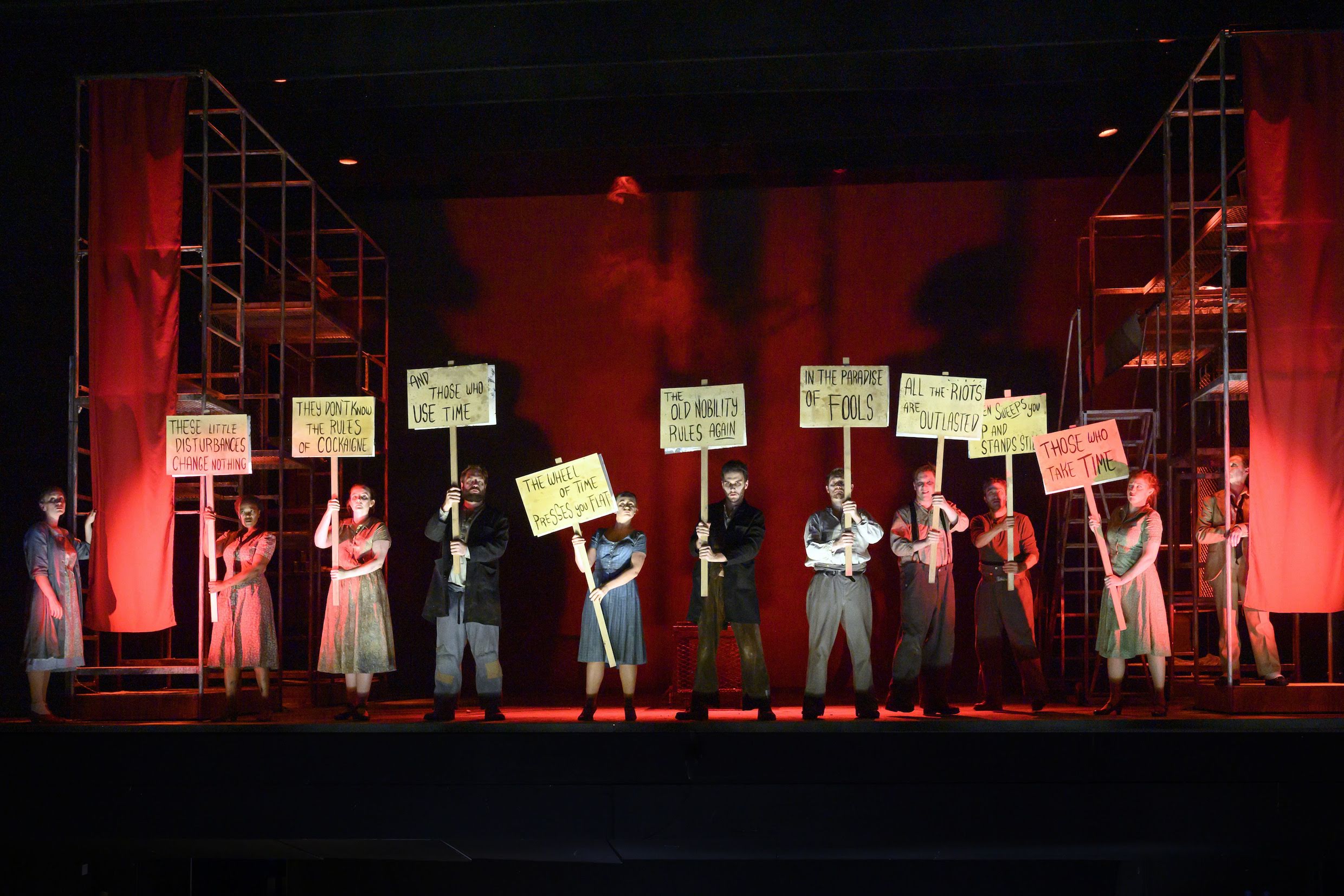

The Silver Lake begins in satire and ends in symbolism. It follows the fate of a jobless worker, Severin, his entanglement with the conscience-stricken policeman who shoots and injures him, Olim, and their final journey towards a reconciliation that has both political and mystical dimensions (pictured above, David Webb as Severin and Ronald Samm as Olim). This version, directed by James Conway and conducted by James Holmes, radically slims down Kaiser’s dialogue and so tilts the balance of the work towards, if not full-blown opera, then at least the classic Singspiel. (ETO are playing it alongside another such hybrid, Mozart’s The Seraglio). The shadow of Weill’s recent sidekick Brecht falls across the production in many ways, not least in the alternation of English for the spoken dialogue and German for most of the sung numbers (except for the Chorus, who deliver their warnings and admonitions in English). In case this dose of Verfremdungseffekt doesn’t do the trick of keeping us alert, the translated lyrics for the songs sometimes appear on screens, sometimes scrawled on placards, inscribed on scrolls or even spooled on spindles that unfurl the text across the stage. Alienated? I’m afraid I was: a bright idea has got confusingly out of hand.

Adam Wiltshire’s set, with its multi-purpose, mobile blocks of scaffolding against a palette of gloomy earth colours, creates a melancholy backdrop for this fable of humanity at the end of its economic and spiritual tether. The opening scenes of the mutinous unemployed (pictured below) as they “bury” the hunger that tyrannises them and then raid a grocer’s shop for food seem to belong to the sardonic, serio-comic Brecht-Weill domain that the audience might recognise. Bernadette Iglich – also the choreographer – acts as a narrator, though more subdued than the familiar snarky Brechtian MC (Joel Grey she doesn't pretend to be). When angry Severin (David Webb, whose accent and diction took a while to settle) steals not solid grub but a pineapple, emblem of aspirational luxury, we realise that Kaiser has led us far from the terrain of simple agitprop.  As the “country policeman” Olim, who first persecutes the poor but then discovers his solidarity with them, Ronald Samm’s baritone has a sympathetic gravitas that anchors the strange voyage we will take with him. As for the orchestra, I missed at first the finely sharpened punch and rasp that Weill’s upbeat numbers demand. However, the granitic chorales – with shades not only of Mozart’s Flute but Bach and Brahms – had a moody grandeur greatly enhanced by the singers from Streetwise Opera (which works with people affected by homelessness).

As the “country policeman” Olim, who first persecutes the poor but then discovers his solidarity with them, Ronald Samm’s baritone has a sympathetic gravitas that anchors the strange voyage we will take with him. As for the orchestra, I missed at first the finely sharpened punch and rasp that Weill’s upbeat numbers demand. However, the granitic chorales – with shades not only of Mozart’s Flute but Bach and Brahms – had a moody grandeur greatly enhanced by the singers from Streetwise Opera (which works with people affected by homelessness).

When a lottery agent announces that Olim has won a fortune (another hint that we have quit social realism for fairy-tale territory), his jaunty tango gives us a sparkling shot of Weill at his drolly parodic peak. James Kryshak, who sings it splendidly, comes closer than any of the cast to the Berlin-to-Broadway tradition of Weill and his heirs that you can now see embodied in the Fox TV series Fosse/Verdon. But this work is a very different beast: more semi-allegorical pantomime than sarcastic cabaret. By the time Olim has installed the wounded Severin in the castle he has bought with his winnings, where the decayed aristocratic housekeeper Frau von Luber (the commanding and sinister Clarissa Meek) holds sway, the element of political parable has fused with a vein of fin-de-siècle symbolism. It recalls the sort of dreamy mystic drama that bewitched composers, from Debussy to Schoenberg, in the plays of Maeterlinck. Even here, curiously, Weill the bittersweet hit-maker surfaces in the catchy songs of the housekeeper’s poor relation Fennimore. They are effectively sung by Luci Briginshaw in a light soprano that, wisely, never mimics either the sweetened sandpaper of Lotte Lenya (the original Fennimore) or the smoke and steel of Ute Lemper.  Although vigorously played and ably sung, especially in Olim and Severin’s later duets, it’s perhaps inevitable this Silver Lake feels underpowered when confronted with the work’s bewildering shifts between tones and registers. After Severin has forgiven Olim, they jointly walk into the sunset of hope across a frozen lake that bears their weight. It comes decorated with silver-paper billows that can’t help but look anticlimactic in comparison with the figurative heft invested in their new-found harmony. The pair dream of a world where men “neither attack nor flee” one another but “meet halfway on level ground”. For all Weill’s tireless wit and invention as a composer, for all Kaiser’s rule-flouting dramatic technique, it could be that their compound genre – an alloy of musical and opera, satire and pageant, political critique and symbolic vision – never quite gelled. That artistic ideal, like the utopian hopes of the characters, stays tantalisingly out of reach, hovering somewhere not just across the lake but over the rainbow (once or twice, I even caught an odd pre-echo of The Wizard of Oz). This remains a problematic work from – heaven knows – a problematic time. But ETO deserves the warmest ovation for the craft and commitment they bring to bear on it.

Although vigorously played and ably sung, especially in Olim and Severin’s later duets, it’s perhaps inevitable this Silver Lake feels underpowered when confronted with the work’s bewildering shifts between tones and registers. After Severin has forgiven Olim, they jointly walk into the sunset of hope across a frozen lake that bears their weight. It comes decorated with silver-paper billows that can’t help but look anticlimactic in comparison with the figurative heft invested in their new-found harmony. The pair dream of a world where men “neither attack nor flee” one another but “meet halfway on level ground”. For all Weill’s tireless wit and invention as a composer, for all Kaiser’s rule-flouting dramatic technique, it could be that their compound genre – an alloy of musical and opera, satire and pageant, political critique and symbolic vision – never quite gelled. That artistic ideal, like the utopian hopes of the characters, stays tantalisingly out of reach, hovering somewhere not just across the lake but over the rainbow (once or twice, I even caught an odd pre-echo of The Wizard of Oz). This remains a problematic work from – heaven knows – a problematic time. But ETO deserves the warmest ovation for the craft and commitment they bring to bear on it.

Add comment