Larry Kramer: 'I think anger is a wonderful useful emotion' | reviews, news & interviews

Larry Kramer: 'I think anger is a wonderful useful emotion'

Larry Kramer: 'I think anger is a wonderful useful emotion'

Remembering the AIDS activist who wrote The Normal Heart and the screenplay for Women in Love

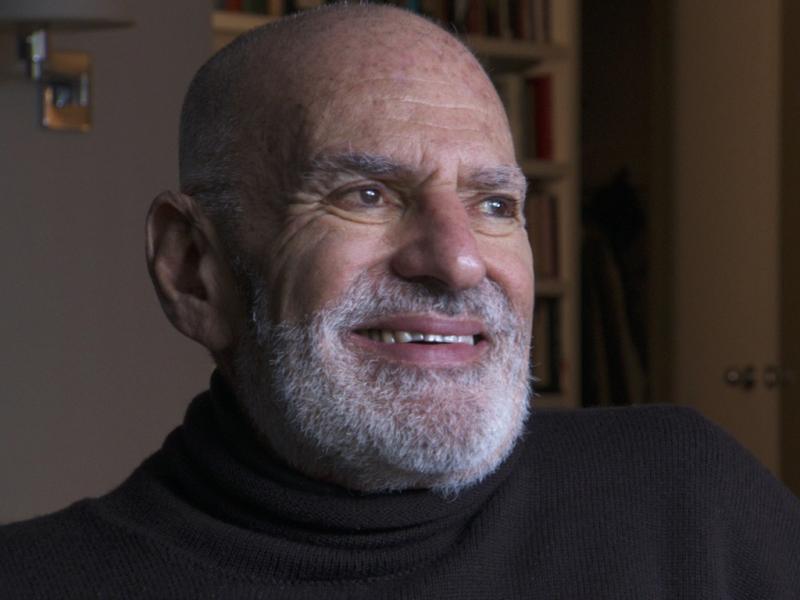

Larry Kramer, who has died at the age of 84, was the Solzhenitsyn of AIDS who indomitably reported from the gay gulags of Manhattan’s quarantined wards and revolving-door hospices. “I felt very much like a journalist who realises that he has been given the story of his life,” he told me when I met him.

His most celebrated work, The Normal Heart, was a polemic about the early years of the virus, in which he took the medical and political establishment to task for not doing enough to protect its victims from the plague. “I’d had a very unsuccessful attempt to write a play before, but I knew that Hollywood wouldn’t touch anything gay and a novel would take too long so I wrote a play because I could get it out faster.” It opened in New York in 1985, while the Royal Court production in 1986 starred Martin Sheen as Ned Weeks, Kramer’s infected alter ego.

The Normal Heart has been produced many hundreds of times all over the world. While it was eventually filmed in 2014 by HBO (pictured right), directed by Ryan Murphy and starring Mark Ruffalo, for 10 years Barbra Streisand held the rights. “There’s no question she was terrified of dealing with the emotional aspects of it, even though her son is gay. She claims that she couldn’t get the finance, which is absurd. She’s not a woman who likes to spend her own money.” In person Kramer was small, softly spoken and even reflective, but he was unabashed about insulting even his own allies into submission.

The Normal Heart has been produced many hundreds of times all over the world. While it was eventually filmed in 2014 by HBO (pictured right), directed by Ryan Murphy and starring Mark Ruffalo, for 10 years Barbra Streisand held the rights. “There’s no question she was terrified of dealing with the emotional aspects of it, even though her son is gay. She claims that she couldn’t get the finance, which is absurd. She’s not a woman who likes to spend her own money.” In person Kramer was small, softly spoken and even reflective, but he was unabashed about insulting even his own allies into submission.

His reputation as a writer actually rests on a relatively slender body of work, among which is the screenplay of Ken Russell’s Women in Love, Kramer, in his phrase, “grew up” in London, where he worked in film for the entire 1960s. “It was hard being in the film industry as an executive. You were expected to show up at all the premieres with a woman on your arm. The gay bars were very much the knock-three-times-and-whisper-hello kind of places. I spent a lot of time going to Amsterdam.”

Kramer’s novel Faggots, published three years before Aids was discovered, warned the promiscuous gay male that he was on a slippery slope to perdition. “I was crucified in the gay press and by mainstream literary critics but the book sold like hot cakes.” It was a novel-length harangue aimed at the man who became his partner. They first met in 1966: “We picked each other up in the Met, had sex and that was it. In ‘71 or ‘2 we met again, completely unaware of the previous time, and that happened about three times until somebody said, ‘Hey, you look familiar.’ So we started seeing each other. It did not go well. We didn’t see each other for 17 years.” If the book is to be believed, they separated because Kramer was much keener on fidelity.

Kramer’s considerable wealth rested less on the success of the play than on a vast and well invested fee for the screenplay of the disastrous 1972 remake of Frank Capra’s classic fantasy epic Lost Horizon. It liberated him to become the most audible AIDS activist in America. “I think anger is a wonderful useful emotion and nothing to be ashamed of,” he said. “It took me a long time to come to that, to make it constructively useful rather than just an outlet. The coming of HIV allowed all that. I don’t know why I am the way I am but I’m I’m glad of it.”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment