'Composing supports children to understand music from the inside': educator Nancy Evans on a revolution in primary schools | reviews, news & interviews

'Composing supports children to understand music from the inside': educator Nancy Evans on a revolution in primary schools

'Composing supports children to understand music from the inside': educator Nancy Evans on a revolution in primary schools

Birmingham Contemporary Music Group's Director of Learning outlines a bold new project

Next month (July 2020) marks 20 years since I started work at Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, initially as their first Education Manager and then in my current role as Director of Learning and Participation.

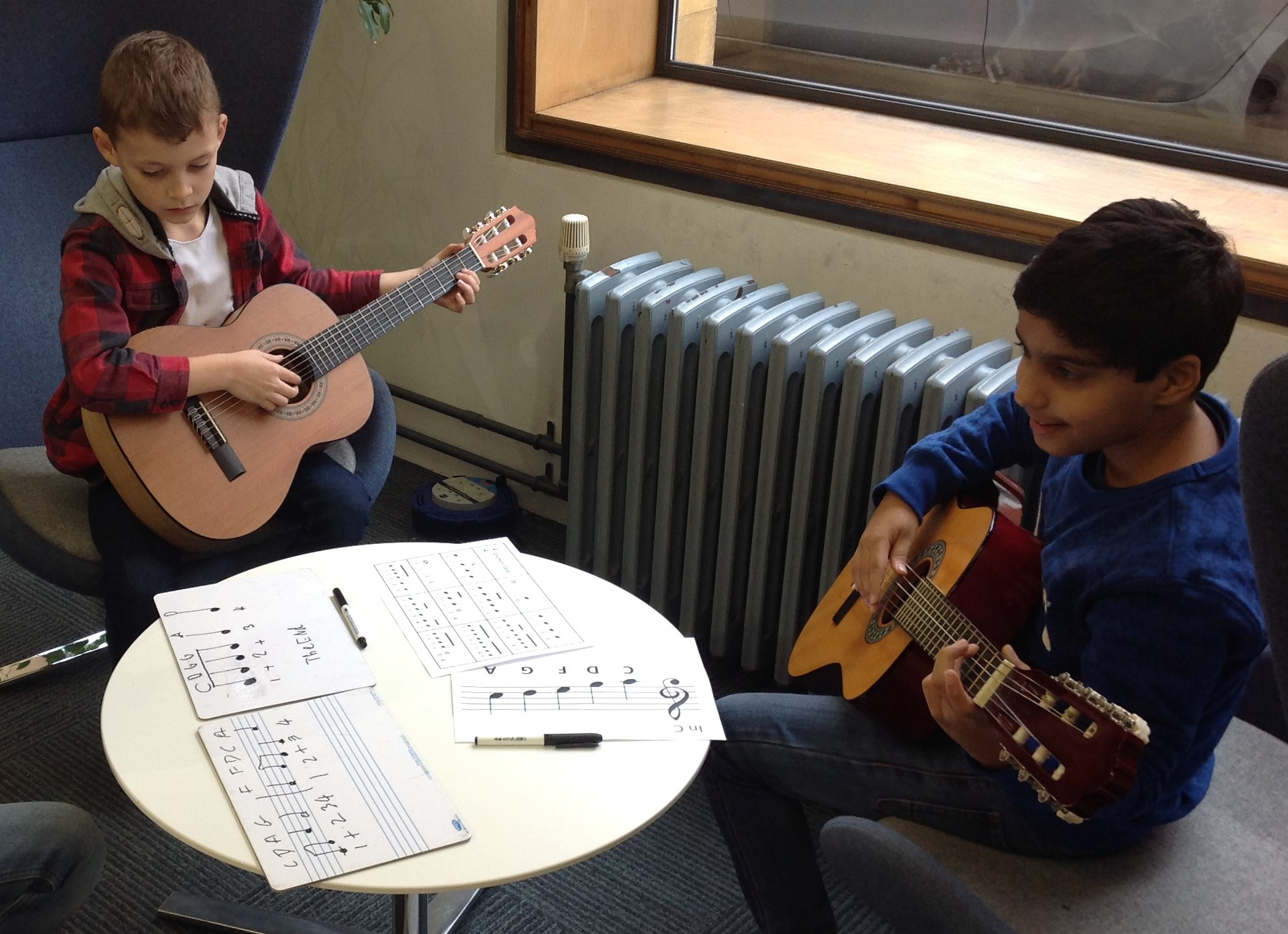

Listen Imagine Compose Primary is a three-year project that will see BCMG work with children, teachers and composers in six Birmingham and three Bristol primary schools to better understand how children compose and progress as composers, and to improve the quality of teaching. It is a partnership between BCMG, Sound and Music, Birmingham City University, Birmingham Music Education Partnership, Bristol Plays Music and the individual schools and builds on several earlier projects led by BCMG that sought to improve music-making and composition in schools.

Despite composing being part of the National Curriculum in KS1, 2 and 3 since 1987, it has remained a challenge for many teachers - this is sometimes even true for those teachers in secondary schools with high-level music training. Many of BCMG’s programmes and projects have focused on creating opportunities for young people to compose (in and out of school) and through supporting their teachers. Like many orchestras and ensembles, this has meant sending composers and musicians into schools. But whilst these projects are important and can have an inspiring influence, often the underlying problems and challenges that face teachers have not been addressed. (The author pictured below).  It is important to clarify here what we mean by composing and what composing for primary school children might look like. Quoting the composer Edgard Varèse, whose music BCMG explored earlier this year, music is “organised sound2 and sowhat we are asking children to do is to play with sound and organise it with intention. We talk about “doing like a composer” and “thinking like a composer”.

It is important to clarify here what we mean by composing and what composing for primary school children might look like. Quoting the composer Edgard Varèse, whose music BCMG explored earlier this year, music is “organised sound2 and sowhat we are asking children to do is to play with sound and organise it with intention. We talk about “doing like a composer” and “thinking like a composer”.

Doing like a composer might be concerned with the techniques of composing, whereas thinking like a composer is concerned with how children make intentional choices about sounds, how they put them together, and how they become aware of the impact of their choices. Often the former is prioritised over the later, but it need not be that way.

Why is composing so important? Composing supports children to understand music from the inside. This in turn supports them to perform and listen to music differently. Composing is an outlet and medium from children’s expression and creativity. From my work as an early years’ music educator I witnessed very young children composing music. This cemented my belief that creating music is something everyone does and can do if given the opportunity. One of the most important things I learnt in this work was to listen to and understand children’s music. How do you hear what is going on when the child’s music sounds nothing like that of adults? How do you respond and what questions do you ask to support learning?

There are many questions to uncover. When scoping out the project, a question we kept coming back to was, what is the difference between a child in Year 1 making a soundscape about the jungle and a child in Year 6 making a soundscape about space? What is different in how the task is presented to them? What different expectations will we have of the children? What composing techniques and processes will we require them to use? What will have changed in how they think about and play with sound and musical ideas? What does a progressive curriculum look like that supports children to build their composing skills, knowledge and practice? What are the implications of working from the children’s own ideas or from an external brief? And what is the balance here that supports children to grow as composers and feel ownership of the music they make?

Listen Imagine Compose Primary will be much bigger than any of our previous school-based projects. Not only will we have composers working with nearly 500 children; we will have a team of researchers from Birmingham City University, led by Professor Martin Fautley, working with us to ensure the learning is captured, analysed and shared widely. We don’t know of any other longitudinal study of this kind.  Working with the children for two years, following them from Year 4 to Year 5, will allow us to see their progress over the long term but also allow us to support teachers to try out the materials and ideas in year one of project with their new Year 4 classes in year two of the project. The children will be invited to compose from their own ideas and from a range of starting points – existing music, science, art, poetry. As well as the workshops in schools, teachers, composers and researchers will meet and reflect together both in the schools and as a whole project.

Working with the children for two years, following them from Year 4 to Year 5, will allow us to see their progress over the long term but also allow us to support teachers to try out the materials and ideas in year one of project with their new Year 4 classes in year two of the project. The children will be invited to compose from their own ideas and from a range of starting points – existing music, science, art, poetry. As well as the workshops in schools, teachers, composers and researchers will meet and reflect together both in the schools and as a whole project.

We will be working with a very diverse group of schools from some supporting the most disadvantaged children in the country to those in leafy suburbs. They also represent a massive diversity in terms of how music is taught within their school: from specialist music teachers with a musical background to generalist teachers with no musical training, from schools where music is delivered by one specialist music teacher to schools where all the music teaching is delivered by generalists and all the permutations in between. This will make the project findings much more relevant post project to a wider group of schools and therefor hopefully have more influence and impact.

How we proceed will be underpinned by the premise and values of expertise being shared between teachers and composers, respect and understanding for the context, ensuring the composing engages all children in creative thinking and using action research as a way to ensure learning of all those involved.

- To be kept informed about the project and its developments please email nancy@bcmg.org.uk

- Read classical reviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Alexander’s Feast, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan review - rapturous Handel fills the space

Pure joy, with a touch of introspection, from a great ensemble and three superb soloists

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

BBC Proms: Moore, LSO, Bancroft review - the freshness of morning wind and brass

English concert band music...and an outlier

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

Willis-Sørensen, Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra, Wilson, Cadogan Hall review - romantic resilience

Passion, and polish, from Kyiv's musical warriors

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Faust, Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Nelsons review - grace, then grandeur

A great fiddler lightens a dense orchestral palette

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Jansen, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - confirming a phenomenon

Second Prom of a great orchestra and chief conductor in waiting never puts a foot wrong

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

BBC Proms: Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Mäkelä review - defiantly introverted Mahler 5 gives food for thought

Chief Conductor in Waiting has supple, nuanced chemistry with a great orchestra

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Dunedin Consort, Butt / D’Angelo, Muñoz, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - tedious Handel, directionless song recital

Ho-hum 'comic' cantata, and a song recital needing more than a beautiful voice

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

Classical CDs: Dungeons, microtones and psychic distress

This year's big anniversary celebrated with a pair of boxes, plus clarinets, pianos and sacred music

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Liu, Philharmonia, Rouvali review - fine-tuned Tchaikovsky epic

Sounds perfectly finessed in a colourful cornucopia

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

BBC Proms: A Mass of Life, BBCSO, Elder review - a subtle guide to Delius's Nietzschean masterpiece

Mark Elder held back from blasting the audience with a wall of sound

Add comment