Before he published fiction, George Saunders trained as an engineer and wrote technical reports. The Booker-winning author of Lincoln in the Bardo, and four volumes of short stories, still has a telling fondness for precisely-scaled kits, blueprints, models and miniatures. One of his typically hands-on, rolled-sleeves analogies in this book about the art of the short story – and the Russian giants who can help us understand it – involves the Hot Wheels table-top race-track that Saunders enjoyed as a kid. The player had to site little gas-stations, with hidden accelerators inside, at intervals along the circuit to help speed the cars around. For Saunders, “The reader is the little car.” As for the author, she must position the gas-pumps of “writerly charm” along the route “so that the reader will keep reading and make it to the end of the story”.

It all sounds a bit folksy, reductive, technocratic. Engineers, though, may design small but think big. The best stories, such as the seven gems Saunders dismantles and rebuilds here, deliver “scale models of the world”. Properly crafted, he writes, they function “not as something decorative but as a vital moral-ethical tool”: DIY kits for a fuller, richer life. To him, fiction itself counts as “the most effective mode of mind-to-mind communication ever devised”. It turns out that our humble mechanic, tinkering quietly under the bonnet, has become one of the engineers of human souls.

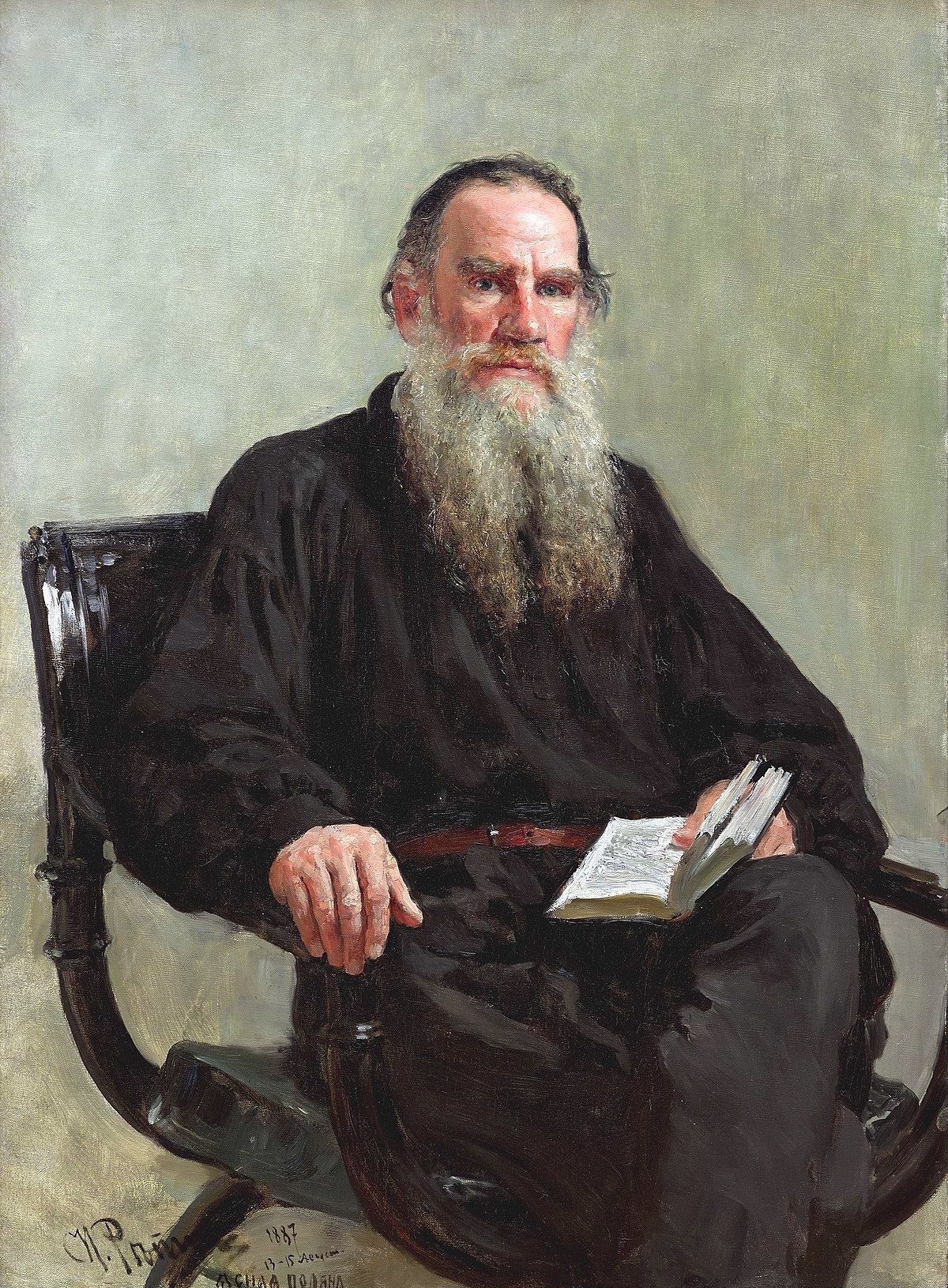

For more than two decades, Saunders has taught the classic Russian tales he loves in a creative-writing MFA programme at Syracuse University. A Swim in a Pond in the Rain selects seven old favourites – three by Chekhov, two by Tolstoy, one each from Gogol and Turgenev – and invites us into his classroom (or garage) as he gets to work on them. He prints each story in its entirety before the business of dissection and reflection starts. Hence, whatever its other virtues, this volume serves as a mini-anthology of great Russian fiction from the 1830s to the 1900s. Among the stand-out items are Gogol’s surreal, unsettling “The Nose”, Tolstoy’s “Master and Man” [right: Leo Tolstoy by Ilya Repin; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow] – a bleaker, more ambiguous Russian cousin to Dickens’s A Christmas Carol – and Chekhov’s “The Darling”, with its-over-loving, over-grieving doormat-turned-dictator heroine, Olenka.

For more than two decades, Saunders has taught the classic Russian tales he loves in a creative-writing MFA programme at Syracuse University. A Swim in a Pond in the Rain selects seven old favourites – three by Chekhov, two by Tolstoy, one each from Gogol and Turgenev – and invites us into his classroom (or garage) as he gets to work on them. He prints each story in its entirety before the business of dissection and reflection starts. Hence, whatever its other virtues, this volume serves as a mini-anthology of great Russian fiction from the 1830s to the 1900s. Among the stand-out items are Gogol’s surreal, unsettling “The Nose”, Tolstoy’s “Master and Man” [right: Leo Tolstoy by Ilya Repin; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow] – a bleaker, more ambiguous Russian cousin to Dickens’s A Christmas Carol – and Chekhov’s “The Darling”, with its-over-loving, over-grieving doormat-turned-dictator heroine, Olenka.

Saunders’s artisanal focus tends to shift our gaze away from history and context. All the same, he insists that he regards these works as “resistance literature, written by progressive reformers in a repressive culture”. Above all, the tales pay attention – visionary, transformative attention – to humble and slighted people who lead downtrodden lives. They include the schoolmistress drudge of Chekhov’s “In the Cart” [below: Anton Chekhov by Osip Braz; Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow], the long-suffering coachman stranded in snowdrifts in “Master and Man”, and the routinely humiliated serving boy in Tolstoy’s “Alyosha the Pot” – who finds, thanks to the equally lowly cook Ustinya, that a person who has nothing can still be needed, still be loved.

Saunders loves these works like old friends who never let him down, and always have something new to say. He does his fair share of minute structural analysis, stripping the engines down to show us how they go. But his warmth, enthusiasm and homespun metaphors – all part of that “writerly charm” – banish any sense of the chilly, mechanistic Fiction Lab. Wannabe short-story writers will no doubt learn a lot: from the ratchet of “increased specification” that a successful story needs, to plot as a “system of escalation”, and the value of patterned repetition, since “pattern creates propulsion”. He numbers himself among those authors for whom writing means rewriting: any finished work is born from “thousands of editing micro-decisions”. And he advocates drastic cutting exercises as a “gateway to voice”. In his experience, such tough revision separates the dilettantes from the real prospects among his students; as does the command of causality, that authorial “superpower” that “is to the writer what melody is to the songwriter”. Yet “presentational excess” and wayward digression have their place as well, as in Turgenev’s “The Singers” – with its shovelfuls of tavern scene-setting that seem (but only seem) to lead nowhere very much.

In the end, however, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain gleefully overshoots its brief as a technical manual or how-to guide. About Gogol’s bizarrely hilarious “The Nose” (with its proboscis that flees its owner’s face to gad about St Petersburg dressed as a top civil servant), he rightly says that what we want from a sentence, a story, a book, is not mechanical efficiency but “joy (overflow, ecstasy, intensity)”. Underneath the engineer’s tunic, the prophet’s heart beats. For Saunders, technical decisions invariably become not just aesthetic but moral choices – such as the elliptical treatment of Alyosha’s heartbreaking departure. Does Tolstoy endorse the exploited lad’s passivity, perhaps “more evasive than saintly”, or does he condemn it? Both, and neither.

In the end, however, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain gleefully overshoots its brief as a technical manual or how-to guide. About Gogol’s bizarrely hilarious “The Nose” (with its proboscis that flees its owner’s face to gad about St Petersburg dressed as a top civil servant), he rightly says that what we want from a sentence, a story, a book, is not mechanical efficiency but “joy (overflow, ecstasy, intensity)”. Underneath the engineer’s tunic, the prophet’s heart beats. For Saunders, technical decisions invariably become not just aesthetic but moral choices – such as the elliptical treatment of Alyosha’s heartbreaking departure. Does Tolstoy endorse the exploited lad’s passivity, perhaps “more evasive than saintly”, or does he condemn it? Both, and neither.

The art of omission – another cardinal virtue in his book – lets contradictions thrive in the reader’s imagination. They seed our ability to share other lives from within rather than seek abstract lessons in what they ought to mean. Sometimes, as here, it’s “the swerving away, the deletion, the declining to decide, the falling silent, the waiting to see” that guarantees the truth of fiction.

Fix a story’s formal problems of voice, or pace, or structure, Saunders argues, and you’ll expel moral – even political – shortcomings from it too: “if that failing is addressed, it will (always) become a better story”. Really? Perhaps an innate American optimism about the alignment of ethics and technique tilts his outlook here. His chosen authors, humanistic lions all (although Tolstoy, as he admits, could be an utter pain in family life), tend to ratify this thesis. After all, they blend stellar craftsmanship with a tireless empathy for the insulted and injured. But Dostoevsky – in his own way both more divine, and more demonic, than this bunch – would have muddied his waters. So would later authors whose stories marry technical prowess with a more tangled or shadowed morality. Would Kipling or Kafka fit this craft-makes-virtue formula? Only at a stretch.

Russian speakers will also worry that, for much of the book, Saunders says little about the translations that he cites. The word choices, the sentence flows, the nuances of voice and tone, that add to the effects he examines depend here on the stories’ Anglophone interpreters. At times, as when he compares various English versions of Alyosha’s end (both published and specially commissioned from Russian-speaking colleagues), he shows a deep sensitivity to translation’s high stakes, its risks and wins – or losses. But it’s insight inconsistently applied.

Russian speakers will also worry that, for much of the book, Saunders says little about the translations that he cites. The word choices, the sentence flows, the nuances of voice and tone, that add to the effects he examines depend here on the stories’ Anglophone interpreters. At times, as when he compares various English versions of Alyosha’s end (both published and specially commissioned from Russian-speaking colleagues), he shows a deep sensitivity to translation’s high stakes, its risks and wins – or losses. But it’s insight inconsistently applied.

Never mind: A Swim in a Pond in the Rain generates more fun, more wit, more sympathetic sense, than we have any right to hope for from a 400-page critical study. Good fiction, to Saunders, reinforces our “moral armament” with the discovery that “everything remains to be seen”. It leaves us “slightly undone” with its revelation, from within, of other lives and other souls; with the salutary reminder that “my mind is not the only mind”. But for all his nuts-and-bolts advice, Saunders doesn’t want his students to write like Chekhov or Tolstoy (as if they could!). Their work should simply “speak to our time as freshly as these Russian stories spoke to theirs”. In another of those sassy similes, he likens an apprentice story he once wrote to a hunting-dog sent out to retrieve some “magnificent pheasant”. It comes back instead with a piece of trash, “let’s say, the lower half of a Barbie doll”. Still, it was his own debris: a “little shit-hill” with “my name on it”. With help from his quartet of friendly Russian ghosts, Saunders points the way up a taller, sweeter hill.

- A Swim in a Pond in the Rain (In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Reading, Writing, and Life) by George Saunders (Bloomsbury, £16.99)

- Boyd Tonkin has been awarded the 2020 Benson Medal of the Royal Society of Literature

Add comment