Gillam, Hallé, Bloxham, Hallé online review - music of poetry | reviews, news & interviews

Gillam, Hallé, Bloxham, Hallé online review - music of poetry

Gillam, Hallé, Bloxham, Hallé online review - music of poetry

Turbulence, calm, and long, slow melodies in a concert commemorating 2020

Jonathan Bloxham makes his debut as conductor with the Hallé Orchestra in the third of the Hallé’s Winter Season concerts on film.

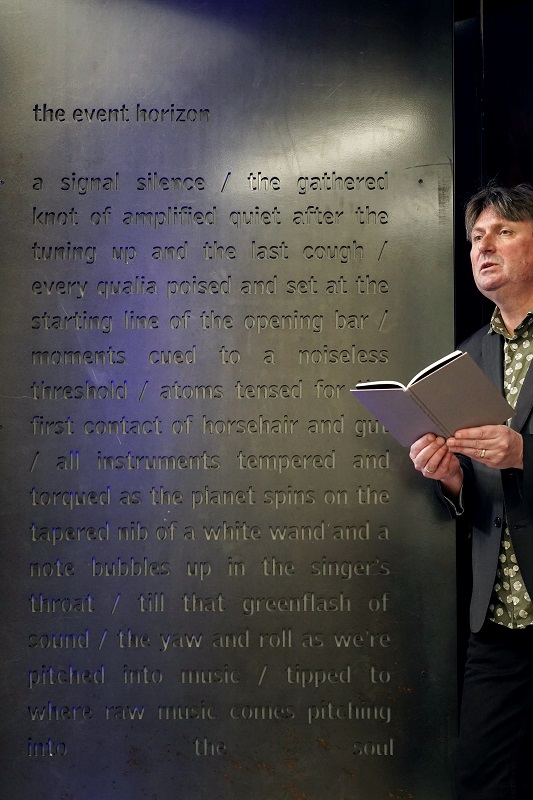

The event horizon is engraved in steel on the Hallé St Peter’s centre (pictured below right with Simon Armitage), where the concert was filmed, and reminds us in one way of what we’re missing: do you remember when concerts used to begin “after the tuning up and the last cough”? (A long time after, if John Barbirolli was conducting – he wouldn’t even walk on until there was absolute hush).

But at least on film they do begin, coughs or no coughs, when you press the arrow, and this one soon gets into Copland’s Quiet City, for strings, cor anglais (Thomas Davey) and trumpet (Gareth Small). The players are in the now-familiar distanced spacing of the Hallé St Peter’s church, and strategically placed lights enhance aspects of the building’s details. The visual mood seems right for music of stillness and calm, with harmonies we easily associate now with wide-open Appalachian vistas – even though this is actually a townscape by night. Bloxham (pictured below) maintains an ebb and flow in its restrained phrases and brings it to a rich conclusion.

But at least on film they do begin, coughs or no coughs, when you press the arrow, and this one soon gets into Copland’s Quiet City, for strings, cor anglais (Thomas Davey) and trumpet (Gareth Small). The players are in the now-familiar distanced spacing of the Hallé St Peter’s church, and strategically placed lights enhance aspects of the building’s details. The visual mood seems right for music of stillness and calm, with harmonies we easily associate now with wide-open Appalachian vistas – even though this is actually a townscape by night. Bloxham (pictured below) maintains an ebb and flow in its restrained phrases and brings it to a rich conclusion.

After that we’re into the first talking bit, with a welcome from the conductor, with orchestra members Paulette Bayley and Dale Culliford describing their affection for the building, and others pointing out how useful it proved in 2020. The element of looking back on last year is also present in the later conversation between Bloxham, composer Hannah Kendall and saxophone soloist Jess Gillam, and that’s perhaps a clue to what Kendall was thinking about when she wrote the six-and-a-half-minute Where is the Chariot of Fire?, a Hallé commission that gets its world premiere on this film.

She talks about "a turbulent year," looking for moments of hope and opportunity, and in the future "clinging on to where and when things might change." Well, we know now that they’ve changed for the worse in many respects, though the hope is still there. But the piece itself has both turbulence and optimism, and a sense of change, even though the poem by Lemn Sissay that provided its title doesn’t include any question mark at the end of the line and might be taken to be a tad morbid in total.

Kendall uses wind-up music boxes, playing “You Are My Sunshine” and “Carrying You” against a cello solo and other voices in her orchestral chorus. Some players vocalise in whispers or humming, and there’s a strikingly insistent repetition of a single pitch, like a bell tolling, as the music slows, then builds in energy before subsiding. “For whom the bell tolls …” – now there’s a poetic thought to remember 2020 with.  More cheerfully, Jess Gillam points out that Glazunov writes for the saxophone as if it were a violin in his Concerto in E flat major for Alto Saxophone and Strings. And so he does. In this, his last work, the saxophone sings. It sings like the music of English between-the-wars naturalism, in its love of sequence, the tonic chord and perfect cadence, its use of jig rhythm and its formal balance. The soloist’s show-off episodes seem a mere concession to the requirements of virtuosity, while long, slow melodies are its heart, and the string writing is lovely. In Jess Gillam’s hands, the saxophone’s solo cadenza section is more than show-off, though: it tells its own passionate tale and brings the concerto’s emotional journey to its high point.

More cheerfully, Jess Gillam points out that Glazunov writes for the saxophone as if it were a violin in his Concerto in E flat major for Alto Saxophone and Strings. And so he does. In this, his last work, the saxophone sings. It sings like the music of English between-the-wars naturalism, in its love of sequence, the tonic chord and perfect cadence, its use of jig rhythm and its formal balance. The soloist’s show-off episodes seem a mere concession to the requirements of virtuosity, while long, slow melodies are its heart, and the string writing is lovely. In Jess Gillam’s hands, the saxophone’s solo cadenza section is more than show-off, though: it tells its own passionate tale and brings the concerto’s emotional journey to its high point.

Simon Armitage, reading Evening (itself a reminiscence of childhood?) leads us into Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite. Jonathan Bloxham draws out the delicate beauty of the writing in its exoticisms, archaicisms and nostalgia – a bonsai garden in music. The film spotlights the bird noises in “Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty”, the orchestra gives vivid colours and dynamic contrasts to “Laideronnette”, principal clarinet Sergio Castelló López plays his role with sleek beauty, and contra-bassoonist Simon Davies his with eery persistence, while Bloxham keeps the underlying waltz pulse rolling along, in “Conversation between Beauty and the Beast”, and the harp and solo violin (Marie Leenhardt and guest leader Kanako Ito) provide the magic both there and in the final “Fairy Garden”, whose last few bars provide an exquisite thrill.

Credits are again due to Maestro Broadcasting and the sound team led by Stephen Portnoi.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment