DVD/Blu-ray: The Masque of the Red Death | reviews, news & interviews

DVD/Blu-ray: The Masque of the Red Death

DVD/Blu-ray: The Masque of the Red Death

Horror is a many-splendoured thing in Roger Corman's 1964 film of Poe's tale

One hundred and seventy four years ago today, on Tuesday, 2 February 1847, the body of Virginia (“Sissy”) Poe, Edgar Allan Poe's 24-year-old wife, was interred in a vault in a graveyard near the couple's rented cottage in Fordham, in the Bronx; she had died of consumption (tuberculosis) the previous Saturday.

Five years previously, Poe had been traumatised by seeing Sissy bleed from the mouth while playing the piano – the first sign she had contracted the “white plague” that had killed his mother when he was two, probably his foster mother, and possibly his brother (more likely a cholera victim). Poe’s response to Sissy’s haemorrhage of the lungs and resulting invalidism was to channel his anguish into the writing of one of his most exquisite stories, “The Masque [originally Mask] of the Red Death”. First published in May 1842, it flees from allegorical interpretations, but it is as mordant as it is melancholy in its appraisal of death’s undeniability. (Pictured below: Death incarnate)

With its colour-themed chambers and decadent medieval suzerain Prince Prospero, who hubristically defies the pestilence that has bloodied and half-depopulated his country by hosting a debauched masqued ball in his impenetrable castellated abbey, the seven-page tale proved the ideal medium for the lush Pop Gothic aesthetic the American director Roger Corman brought to his 1960-65 series of low-budget Poe adaptations. All except one starred Vincent Price at his most mellifluously macabre – or tormented in the case of the first entry, House of Usher. (Released in1963, The Haunted Palace, named after a Poe story but based on an HP Lovecraft novella, is usually considered an eighth title in the Poe-Corman Cycle.)

With its colour-themed chambers and decadent medieval suzerain Prince Prospero, who hubristically defies the pestilence that has bloodied and half-depopulated his country by hosting a debauched masqued ball in his impenetrable castellated abbey, the seven-page tale proved the ideal medium for the lush Pop Gothic aesthetic the American director Roger Corman brought to his 1960-65 series of low-budget Poe adaptations. All except one starred Vincent Price at his most mellifluously macabre – or tormented in the case of the first entry, House of Usher. (Released in1963, The Haunted Palace, named after a Poe story but based on an HP Lovecraft novella, is usually considered an eighth title in the Poe-Corman Cycle.)

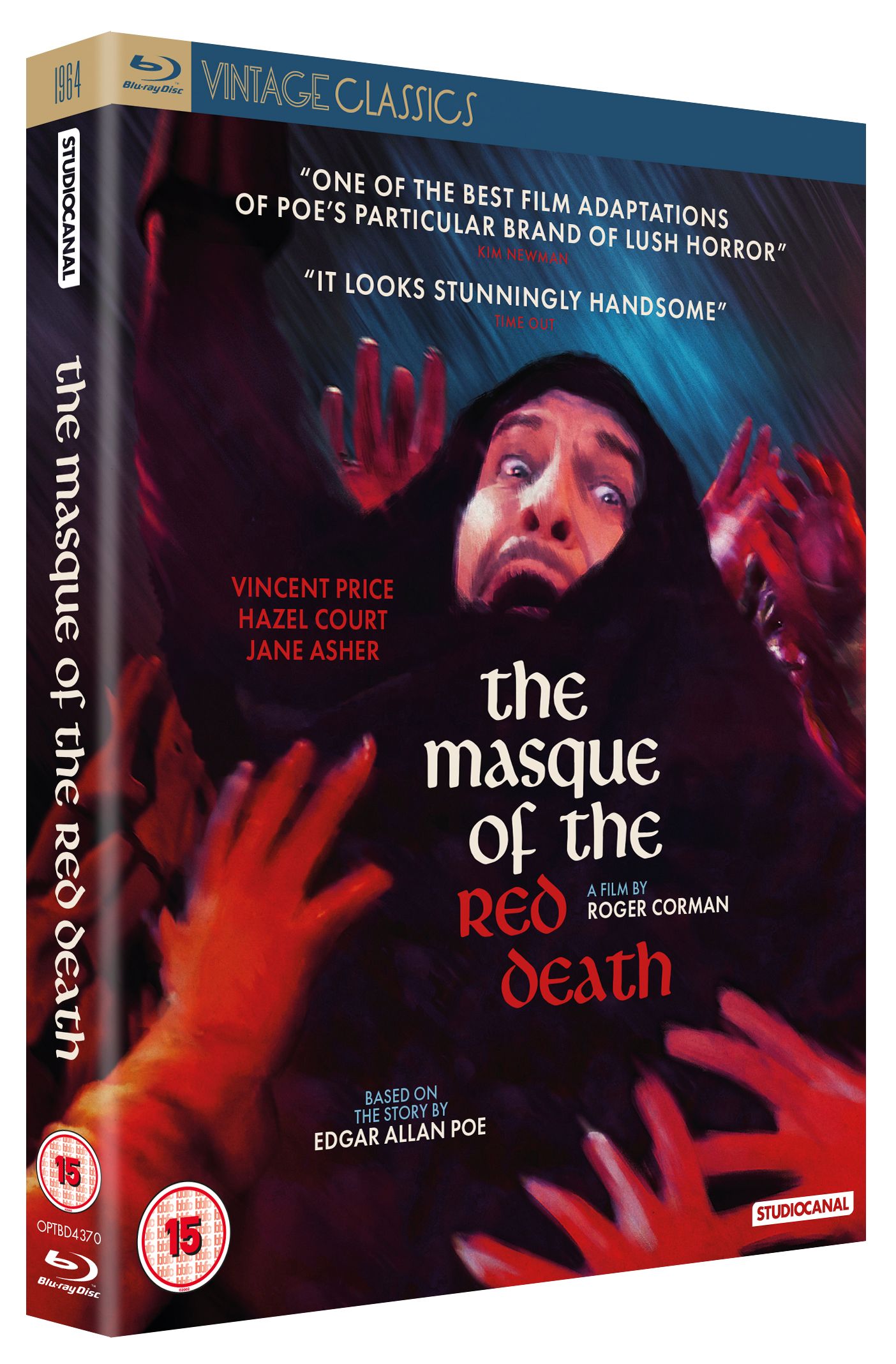

The Masque of the Red Death (1964), which has been restored and released by Studio Canal, was Corman’s penultimate Poe film. He had delayed making it, suspecting that the climactic encounter between Price’s Devil-worshipping Prospero and the shrouded figure of Death would prompt accusations he’d stolen the concept from Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). Screenwriter Charles Beaumont, a visionary horror and sci-fi writer who would die of early-onset ageing diseases at 38 in 1967, wrote the first draft, which introduced Prospero’s satanism, but he was too ill to accompany the production to England, where it was filmed – on the recently vacated Becket sets at Shepperton – to take advantage of tax breaks. Corman enlisted another writer, Robert Wright Campbell, to flesh out the thin story. Campbell wove in Poe’s horrific revenge story "Hop-Frog", but narrative depth and complexity proved elusive.

Seventeen-year-old Jane Asher was cast as the peasant protagonist Francesca, a devout Christian perversely chosen by Prospero as his consort for the ball while she’s protesting his incarceration of her father (Nigel Green) and swain (David Weston). Asher’s role wasn’t so much underwritten as barely written at all; her forgiveness of Prospero for killing one of her loved ones and her vague affection for him is mysterious. These moral peculiarities are mercifully balanced by the retribution the dwarf Hop-Toad (as Hop-Frog was renamed and played by little person Skip Martin) exacts from a sly courtier (Patrick Magee) for lusting after his dancer companion Esmeralda – an adult dwarf played by child actor Verina Greenlaw and troublingly dubbed by a woman – and for throwing wine in her face.

Despite the chaste relationship between Prospero and Francesca, the prince’s spurned mistress (Hazel Court) resolves to give herself to Satan, occasioning a cloudy green dream sequence and facially distorting camera effects supplied by future auteur Nicolas Roeg, whose widescreen Pathécolour cinematography is magnificent throughout. The shots that track beside Prospero – Price at his most suavely degenerate – as he pontificates about the lure of evil before his captive audience of doomed nobles lyricise his insanity.

Despite the chaste relationship between Prospero and Francesca, the prince’s spurned mistress (Hazel Court) resolves to give herself to Satan, occasioning a cloudy green dream sequence and facially distorting camera effects supplied by future auteur Nicolas Roeg, whose widescreen Pathécolour cinematography is magnificent throughout. The shots that track beside Prospero – Price at his most suavely degenerate – as he pontificates about the lure of evil before his captive audience of doomed nobles lyricise his insanity.

It would be surprising to learn that Roeg hadn’t studied the jewelled Technicolor images of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Black Narcissus (1947) before shooting Corman’s canivalesque phantasmagoria. The director’s expressive use of chaotic dance – not in discrete musical sequences but as natural elements of the masque – was meanwhile revelatory in the context of a camp Gothic horror film. The cavortings of Prospero’s guests stop short of pushing the film into abstraction – and there’s nothing here that particularly equates the Red Death with Covid-19 – but they enshrine the self-degrading hedonism of privileged people hurtling toward nothingness, or “dancing on a volcano” as The Rules of the Game’s director Jean Renoir put it in 1939.

Censors demanded the cutting of then-frightening images from The Masque of the Red Death before its original release. They’ve been returned on the 4K restoration; the Studio Canal DVD/Blu-ray twins the extended version and the theatrical cut. In a new interview, film lecturer Keith M Johnston analyses Corman and Roeg’s use of colour and the linked issue of the censors’ cuts. Horror expert Kim Newman’s precise, informative 2013 BFI interview with Corman (who’s now 94) includes anecdotes both amusing and sobering, but it makes unnecessary a featurette in which Corman appears solo. Filmmaker Sean Hogan (The Devil’s Business) and Newman provide the entertaining audio commentary.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Freakier Friday review - body-swapping gone ballistic

Lindsay Lohan and Jamie Lee Curtis's comedy sequel jumbles up more than their daughter-mother duo

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

Eight Postcards from Utopia review - ads from the era when 1990s Romania embraced capitalism

Radu Jude's documentary is a mad montage of cheesy TV commercials

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

The Kingdom review - coming of age as the body count rises

A teen belatedly bonds with her mysterious dad in an unflinching Corsican mob drama

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

Weapons review - suffer the children

'Barbarian' follow-up hiply riffs on ancient fears

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

theartsdesk Q&A: filmmaker Dag Johan Haugerud on sex, love, and confusion in the modern world

The writer-director discusses first-love agony and ecstasy in 'Dreams', the opening UK installment of his 'Oslo Stories' trilogy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Dreams review - love lessons

First love's bliss begins a utopian city symphony

Add comment