Bent Coppers: Crossing the Line of Duty, BBC Two review - when crime paid handsomely for corrupt officers | reviews, news & interviews

Bent Coppers: Crossing the Line of Duty, BBC Two review - when crime paid handsomely for corrupt officers

Bent Coppers: Crossing the Line of Duty, BBC Two review - when crime paid handsomely for corrupt officers

Astounding history of how the Met went rotten from within

As Line of Duty aficionados debate the identity of H and wonder who DCI Joanne Davidson shares her DNA with, this new three-part series from BBC Two investigates the history of real-life corruption in the Metropolitan Police.

The story is vividly told through interviews and atmospherically grainy archive footage depicting an old-fashioned London of seedy West End clubs, jolly coppers on the beat (sometimes in fizzy Look at Life colour) and nostalgic clips of Rover and Triumph patrol cars in flashing-light action. It was a time when, as far as the public were concerned, “the police were respected and revered and they epitomised trust and honesty and kindness,” according to former Flying Squad officer Jackie Molton (pictured below). She herself helped to expose police corruption and was the inspiration behind Helen Mirren’s DCI Jane Tennison in Prime Suspect.

The extent of police involvement in this morass of malfeasance had lain largely undiscovered until The Times newspaper published a whistle-blowing story in November 1969, triggered by a South London petty criminal called Michael Perry who was being blackmailed by a couple of Met detectives, DS Gordon Harris and Inspector Bernard Robson. Clandestine tape recordings of conversations between Perry and corrupt officers (many from a recorder hidden in a car boot) give the programme a frisson of immediacy – though the animated sequences illustrating this material were irritatingly feeble – while the factual details are still enough to boggle the mind. In Perry’s case, the cops conned him into thinking they had his fingerprints on a lump of gelignite, which they used as leverage over him.

The extent of police involvement in this morass of malfeasance had lain largely undiscovered until The Times newspaper published a whistle-blowing story in November 1969, triggered by a South London petty criminal called Michael Perry who was being blackmailed by a couple of Met detectives, DS Gordon Harris and Inspector Bernard Robson. Clandestine tape recordings of conversations between Perry and corrupt officers (many from a recorder hidden in a car boot) give the programme a frisson of immediacy – though the animated sequences illustrating this material were irritatingly feeble – while the factual details are still enough to boggle the mind. In Perry’s case, the cops conned him into thinking they had his fingerprints on a lump of gelignite, which they used as leverage over him.

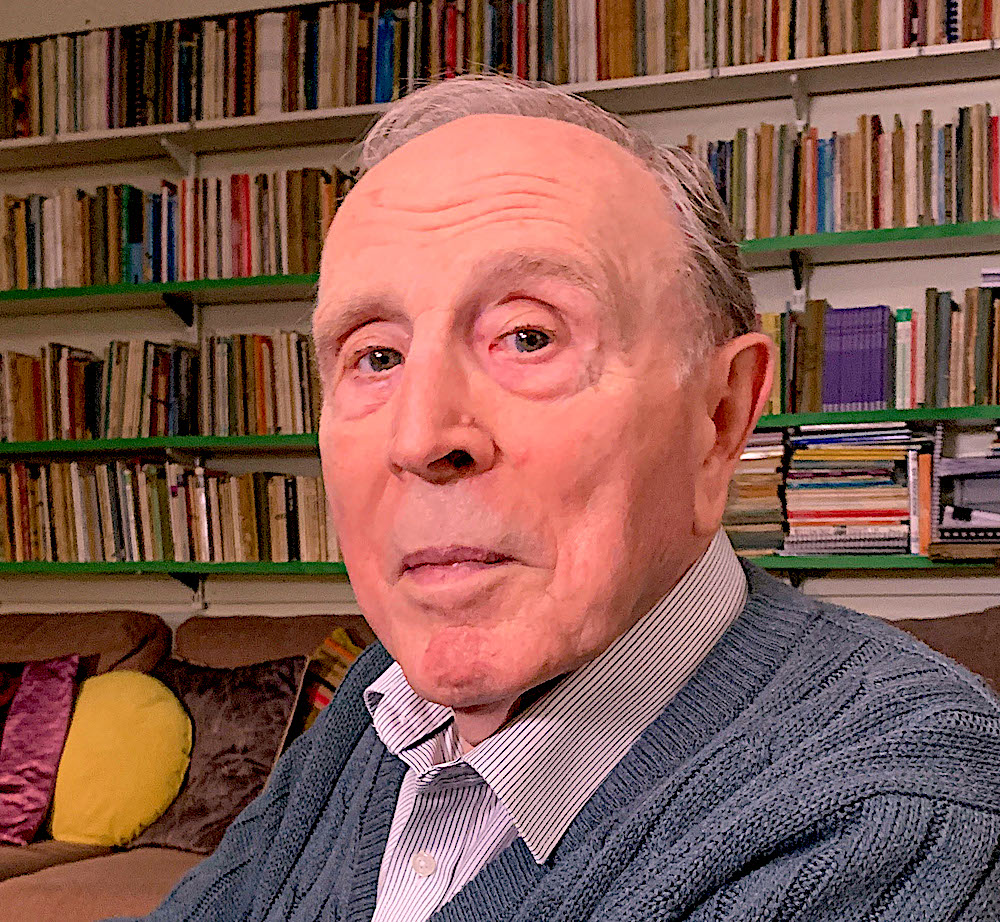

One of the most notorious of the Met’s bent cops was Detective John Symonds (not to be confused with DCS John Simmonds, pictured below, who worked to clean up the force). We hear Symonds matter-of-factly admitting that “I know people everywhere, because I’m in a little firm in a firm” (he’d charge 50 quid a session for giving villains the benefit of his insider knowledge). It seems the Met’s CID was its own hermetically-sealed criminal unit, with its officers forming a tightly-knit cadre of corruption.

The police didn’t just want to take bungs from the criminals on their patch, they wanted to go into business with them and share the proceeds. Thus, we hear Symonds explaining how a criminal, if he played the game, would have carte blanche to commit crimes “round here any time”, and might even be able to call on a bit of police assistance if, for instance, he wanted to raid a pub. The police became so greedy that they ended up seizing the lion’s share of the illicit earnings.

The police didn’t just want to take bungs from the criminals on their patch, they wanted to go into business with them and share the proceeds. Thus, we hear Symonds explaining how a criminal, if he played the game, would have carte blanche to commit crimes “round here any time”, and might even be able to call on a bit of police assistance if, for instance, he wanted to raid a pub. The police became so greedy that they ended up seizing the lion’s share of the illicit earnings.

Needless to say, stamping this out was to prove no easy matter. The article in The Times, then regarded as the Establishment’s in-house journal (not sure it still is), spurred the government into action. The severe and strait-laced Inspector of Constabulary Frank Williamson was sent in to investigate, but he was systematically obstructed by his assistant, DCS Bill Moody. The latter was acting on orders from the outrageously corrupt Commander Wally Virgo, as trustworthy as a three-pound note, to ensure at all costs that the “firm within a firm” was not exposed. Only Harris and Robson were jailed, while the egregious Symonds was given a couple of grand to flee the country and lie low. Incredibly, he was subsequently hired to spy for the KGB, though that wasn’t explored here.

Fascinating stuff, and it makes The Sweeney look like CBeebies. Coming up in next week’s part two – sex, sleaze, Soho, and the Met’s Dirty Squad.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Add comment