Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - a misalliance of metatheatre and the mundane | reviews, news & interviews

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - a misalliance of metatheatre and the mundane

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - a misalliance of metatheatre and the mundane

Singing, playing and conducting urge emotion, production shuts it down

Angels and birds throng the inner life of tragic heroine Katya Kabanova, very much centre-stage in Nikolay Ostrovsky’s The Storm and achingly so in Janáček’s musical portrait. Director Damiano Michieletto takes the feathers, adds cages and claustrophobic white walls, and makes the symbolism the thing.

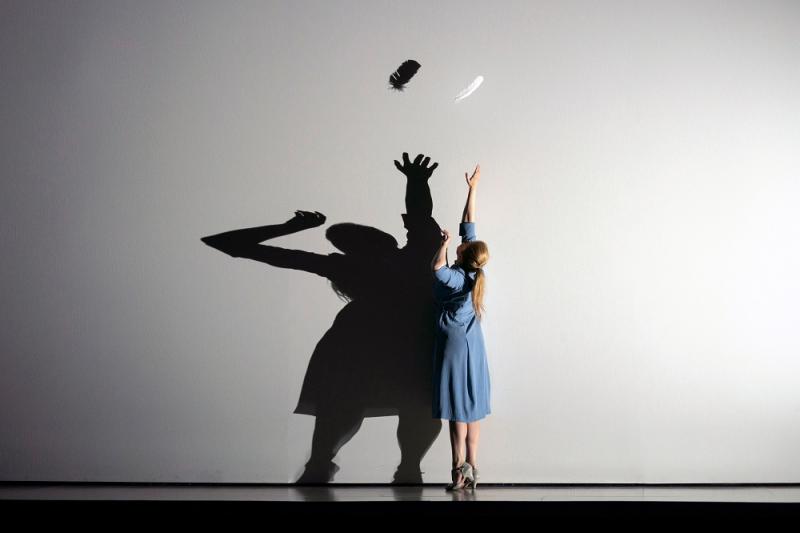

Stephen Langridge, Glyndebourne’s artistic director, nails the problem in the programme by chancing to hit upon what’s absent as he reflects on why we need live performance after a year of semi-silence: “[operatic] characters are observed, but also met”. Here we observe them, but we never really get to meet them. Czech soprano Kateřina Kněžíková has everything needed in the voice for poor Katya: flaming emotion, tenderness, heartbreak. But she never gets to express those things with physical precision, beyond anguished pacing in smart shoes – couldn’t she have taken them off for her garden adventure? – and a silence that’s not filled enough with tension. We need to recognise a real young woman on the edge, as we did so disturbingly with Amanda Majeski’s frighteningly “lived” performance at the Royal Opera in 2019.  The catching of a feather and the shadow of an angel in the orchestral introduction are beautiful images. The trouble begins when the heavenly emissary is embodied in a young man, and then by eight wingless, beautiful others: so distracting, especially in what should be the heroine’s most isolated moments, or her brief moment of private desire about to be fulfilled (pictured above). And what does Katya take out of the first descending cage? Is it a Magritte owl? A rock? An egg? The symbolism, unclear at first, is as heavy as the giant boulder which Olivier Tambosi used to dominate Act Two of Janáček’s Jenůfa at the Royal Opera (also cued when the girl tells her step-mother that she feels as if a stone’s falling on her).

The catching of a feather and the shadow of an angel in the orchestral introduction are beautiful images. The trouble begins when the heavenly emissary is embodied in a young man, and then by eight wingless, beautiful others: so distracting, especially in what should be the heroine’s most isolated moments, or her brief moment of private desire about to be fulfilled (pictured above). And what does Katya take out of the first descending cage? Is it a Magritte owl? A rock? An egg? The symbolism, unclear at first, is as heavy as the giant boulder which Olivier Tambosi used to dominate Act Two of Janáček’s Jenůfa at the Royal Opera (also cued when the girl tells her step-mother that she feels as if a stone’s falling on her).

It’s hard on the realism, too: can you really take in the idea of progressive versus reactionary in Act Three when horrid old Dikoj sings that storms are the punishment of the Almighty while clever young chemist-teacher Kudyash insists it’s electricity? And can you forego married Katya’s one brief, if still temporarily guilt-ridden, al fresco episode of happiness with lover Boris in favour of mother-in-law Kabanicha breaking in and breaking up the chief angel’s wings before shoving him in the cage? The stage pictures, with spare sets by Paolo Fantin, perfect costumes from Carla Teti and deft lighting changes by Alessandro Carletti, is always impressive in itself, as the images you see suggest, but rarely as concordant with the essence of the drama, as their equivalents were in the last, great Glyndebourne Káťa from Nikolaus Lehnhoff..  All the more impressive, then, that the singing actors make their presences felt as strongly as they do. The three tenors represent the cream of young British, or British-trained, singers: Thomas Atkins as a bright-eyed Kudryash, David Butt Philip trying to keep it real in unpromising surroundings as Boris and Nicky Spence as Katya’s rage-filled, alcoholic husband Tikhon, pleading for another sort of production (pictured below on the right in the scene of Katya's confession). A rising star bass, Tom Mole, who's just won the gold medal at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, manages to make an impact in the tiny role of Kudryash's friend Kuligin in Act Three. Kudryash’s girlfriend, less likely to be crushed by her place in the Kabanov household than Katya, is lustrously sung by Aigul Akhmetshiina (pictured above with Atkins). Katarina Dalayman and Alexander Vassiliev as the destructive older ones don’t get enough help from the production; their little sado-masochistic scene together in Act Two Scene One is even more awkward than usual.

All the more impressive, then, that the singing actors make their presences felt as strongly as they do. The three tenors represent the cream of young British, or British-trained, singers: Thomas Atkins as a bright-eyed Kudryash, David Butt Philip trying to keep it real in unpromising surroundings as Boris and Nicky Spence as Katya’s rage-filled, alcoholic husband Tikhon, pleading for another sort of production (pictured below on the right in the scene of Katya's confession). A rising star bass, Tom Mole, who's just won the gold medal at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, manages to make an impact in the tiny role of Kudryash's friend Kuligin in Act Three. Kudryash’s girlfriend, less likely to be crushed by her place in the Kabanov household than Katya, is lustrously sung by Aigul Akhmetshiina (pictured above with Atkins). Katarina Dalayman and Alexander Vassiliev as the destructive older ones don’t get enough help from the production; their little sado-masochistic scene together in Act Two Scene One is even more awkward than usual.

It’s funny how what you see affects what you hear: Robin Ticciati urges ardour, intense pianissimos and sleight-of-hand mood changes from the LPO, superbly impactful in the agitation that kicks off Act Three, but the hard work on detail is much diminished by Michieletto’s take.Pity Ticciati: alongside the successes, he's had so many production turkeys hung around his neck, most recently Claus Guth's La clemenza di Tito and Stefan Herheim's Pelléas et Mélisande.  Are there fewer string players than usual in the pit? It sounded so; the bigger list in the programme is presumably for the fuller forces to be unleashed later in the season on the concert staging of Tristan und Isolde. Again, we observe (in this case with our ears), but aren’t allowed to be deeply moved. Not that the first night of a Glyndebourne season since May 2019 was anything but pleasurable, regardless of wind and rain. Some of the uglier excrescences on the lawns have gone, and an elegant open tent provides easy and pleasant cover if you need to bring in your picnic from inclement weather (we did). Even many of the sculptures this year, by Halima Cassell, work well with the surroundings. Abundant staff are super-helpful and seem as glad as we and the artists are to be there. All that has to be part of the experience. For that and for the vision to go ahead with four productions plus a concert staging, and concerts, we’re truly thankful.

Are there fewer string players than usual in the pit? It sounded so; the bigger list in the programme is presumably for the fuller forces to be unleashed later in the season on the concert staging of Tristan und Isolde. Again, we observe (in this case with our ears), but aren’t allowed to be deeply moved. Not that the first night of a Glyndebourne season since May 2019 was anything but pleasurable, regardless of wind and rain. Some of the uglier excrescences on the lawns have gone, and an elegant open tent provides easy and pleasant cover if you need to bring in your picnic from inclement weather (we did). Even many of the sculptures this year, by Halima Cassell, work well with the surroundings. Abundant staff are super-helpful and seem as glad as we and the artists are to be there. All that has to be part of the experience. For that and for the vision to go ahead with four productions plus a concert staging, and concerts, we’re truly thankful.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Add comment