Remembering Graham Vick (1953-2021) - top colleagues on one of the greatest opera directors | reviews, news & interviews

Remembering Graham Vick (1953-2021) - top colleagues on one of the greatest opera directors

Remembering Graham Vick (1953-2021) - top colleagues on one of the greatest opera directors

Five singers, a conductor and a casting director recall an irreplaceable visionary

Five weeks have passed since the death of opera director Graham Vick from complications due to Covid-19, shocking even to those of us (un)prepared for the worst, and yet so many of us think about him every day.

A personal note on why I'm so stricken before I hand over to those who had far more creative experience of his vision. I first saw his productions when I was a student at Edinburgh University, both in Scotland and at English National Opera in London. His Scottish Opera take on Britten's Billy Budd had such an impact on a still-closeted teenager; it remains the best I've seen, even though Philip Langridge and John Tomlinson reprised their roles elsewhere. At around the same time in the 1980s, a fellow student conjured up the magic of the community experience at Batignano, Italy, which sounded like nothing else I'd ever heard of.

It was replicated, on a grander scale, in Birmingham: opera as communication to everybody, making the audience part of the action, involving in its cast as many local people as possible. I left it a bit late to witness these revelations: Khovanskygate in a big top, with full orchestra on a platform and us standing spectators moved around by Graham and others from TV debate to a big van cordoned by incident tape and policemen pouring out of it - and so many first-rate black singers in the cast - was an eye-opener which made me keen to see more. Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in a disused ballroom brought surprises and inventions I couldn't have imagined in advance. RhineGold in August focused on the work itself, and another stunning conception of it, so that the memorial aspect went out of one's mind for the duration.  I finally came closer to the humanity and generosity of the person through his many willing visits to my Opera in Depth course, first at the Frontline Club and then on Zoom. When I started at the Frontline with 10 Mondays on Prokofiev's War and Peace he joined us and loaned me the film of his second, 2014 Mariinsky production (pictured above), so radical and contemporary - it was just at the time when Putin's forces invaded Crimea, and what he got away with in the face of censorship seemed astounding. I was able to show scenes again in two classes as part of a Russian music course. Graham came along to the second. He arrived at 2.30pm and was still there, firing off ideas and answering questions, three and a half hours later.

I finally came closer to the humanity and generosity of the person through his many willing visits to my Opera in Depth course, first at the Frontline Club and then on Zoom. When I started at the Frontline with 10 Mondays on Prokofiev's War and Peace he joined us and loaned me the film of his second, 2014 Mariinsky production (pictured above), so radical and contemporary - it was just at the time when Putin's forces invaded Crimea, and what he got away with in the face of censorship seemed astounding. I was able to show scenes again in two classes as part of a Russian music course. Graham came along to the second. He arrived at 2.30pm and was still there, firing off ideas and answering questions, three and a half hours later.

As thanks, I sent him two books by the revolutionary writer Victor Serge, one a novel, the other an autobiography, which were waiting for him in the spring when he returned from Italy to the home he shared with his wonderful long-term partner, choreographer Ron Howell. His last email told me that he was about to start work on RhineGold; which should he read first? I suggested the novel because of the big open spaces Serge opens up around and above the constricted Soviet lives of the doomed leading characters. Not having heard more about when the performances were to take place, I emailed again and got the devastating news from Ron that Graham was unconscious in hospital. Of course we thought he'd rally, as Michael Rosen had, so the second blow was unspeakably hard. Thoughts as ever to Ron, who managed to attend one of the Birmingham performances and when I last emailed him was meeting BOC folk to find the right venue for a memorial event - it had to be a warehouse, of course. (Pictured below by Adam Fradgley: Vick with Ron Howell facing him and members of the Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk company). My immense gratitude to the wonderful people who have shed so many different lights on the immortal director and friend below: soprano Sue Bullock, mezzo Chrystal E. Williams, tenor Richard Berkeley-Steele (the only one in the company to have known Graham during his college days), baritone Eric Greene, bass John Tomlinson, casting director/consultant Sarah Playfair and conductor William Lacey. who first made his tribute on Facebook. Two of them have their honours attached; our director became a "Sir" in January, but it was always "just call me Graham". David Nice

My immense gratitude to the wonderful people who have shed so many different lights on the immortal director and friend below: soprano Sue Bullock, mezzo Chrystal E. Williams, tenor Richard Berkeley-Steele (the only one in the company to have known Graham during his college days), baritone Eric Greene, bass John Tomlinson, casting director/consultant Sarah Playfair and conductor William Lacey. who first made his tribute on Facebook. Two of them have their honours attached; our director became a "Sir" in January, but it was always "just call me Graham". David Nice

Susan Bullock CBE, soprano

How do I describe Graham Vick and what he meant to me? It is almost impossible to put into words…but basically, he changed my life.

How do I describe Graham Vick and what he meant to me? It is almost impossible to put into words…but basically, he changed my life.

When I stepped into the role of Butterfly in the early 90s at extremely short notice in his iconic ENO production, he didn't give me an ounce of leeway or make any excuse for it being a rather rushed job…he knew what he wanted and he knew how to get it out of me. That role changed the trajectory of my career. I had previously done some performances of Tatayna in his ENO Eugene Onegin and I knew he was a hard taskmaster, but it was worth every single second. He just knew how to get singers to sing well. We spent hours around the piano, analysing every note, every sound, leaving nothing unattended, and the result was that he equipped me with a huge palette of colours and ideas from which to choose when on stage. I had never met anyone like him and I was bowled over and excited…and a little terrified, too.

We had met many years earlier as he was a friend of a pal of mine from my university days, and I remember a memorable trip to Covent Garden with him to hear Macbeth with Renato Bruson and Renata ScottoI sat next to him and he knew every note and lived every second. It was revelatory to be with someone who had such insight. We became fast friends and I jumped at the chance to go to Batignano to be part of the italian premiere of King Priam in 1990…or "Re Priamo" as it was called. That was a blissfully happy time: great pals, an idyllic setting and a typically “Graham” production, full of invention at every turn. He had just met his partner Ron Howell and it was wonderful to see him so happy.

Other memorable projects included another late jump in as Lisa in The Queen of Spades at Glyndebourne. Once again, he pushed me to dig deeper and deeper. His standards were high and his work ethic was second to none, and he expected that of everyone he worked with. Another wonderfully happy summer with both Graham and Ron…

And then…the Ring in Lisbon. Where do I start to try and describe this experience? In true GV style, he tore all the seats out of the auditorium and placed them on the stage, had a stage erected in the gap where the stalls seats had previously been, which meant we could get nose to nose with the audiences in the boxes, and the orchestra was placed under this stage and we only had contact via monitors with the conductor. It was amazing and made the connection with the public absolutely immediate. Only Graham could persuade me to play snooker whilst singing the "hojotoho"s, and I was overjoyed on the night that it was recorded for TV to pot the black perfectly on the last sustained top B, much to Graham's amusemen [pictured right: Susan Bullock with Mikhail Kit as Wotan and Judith Nemeth as Fricka]. Each piece of the Ring was examined forensically and with such vision and imagination. Every rehearsal was a thrill and a voyage of discovery, and the performances were relayed on a big screen outside the theatre, such was the demand to see them from the public. We took our curtain calls inside and then ran to the outside to greet the audience in the piazza…I remember them going absolutely crazy and Graham looked at me with a wry smile, squeezed my hand tightly and said “This is the nearest we will ever get to being rock stars!”

And then…the Ring in Lisbon. Where do I start to try and describe this experience? In true GV style, he tore all the seats out of the auditorium and placed them on the stage, had a stage erected in the gap where the stalls seats had previously been, which meant we could get nose to nose with the audiences in the boxes, and the orchestra was placed under this stage and we only had contact via monitors with the conductor. It was amazing and made the connection with the public absolutely immediate. Only Graham could persuade me to play snooker whilst singing the "hojotoho"s, and I was overjoyed on the night that it was recorded for TV to pot the black perfectly on the last sustained top B, much to Graham's amusemen [pictured right: Susan Bullock with Mikhail Kit as Wotan and Judith Nemeth as Fricka]. Each piece of the Ring was examined forensically and with such vision and imagination. Every rehearsal was a thrill and a voyage of discovery, and the performances were relayed on a big screen outside the theatre, such was the demand to see them from the public. We took our curtain calls inside and then ran to the outside to greet the audience in the piazza…I remember them going absolutely crazy and Graham looked at me with a wry smile, squeezed my hand tightly and said “This is the nearest we will ever get to being rock stars!”

I cannot believe that he has gone. I shall miss him more than words can say. We still had so much to say to each other and to do together. But I shall be eternally grateful to the Birkenhead boy who opened my eyes and my mind and showed me a whole new world to explore.

RIP dear friend, you will always be in my heart.

Richard Berkeley-Steele, tenor

I met Graham at the Royal Manchester College of Music in Manchester on our first day in 1971. It was the RMCM’s final year before it became the RNCM, amalgamating with the Northern School of Music. In those days the singers were taught singing, drama, elocution, movement, historical dance (we called it hysterical) and make-up. Various other musical skills made up the education. Of course the singing lessons were the primary reason to being there. Graham had a lyrical baritone voice and a huge theatrical and musical knowledge. He already had an extraordinary intellect and could discuss a wide variety of orchestral and chamber music, recent opera productions on tour and the latest theatre productions.

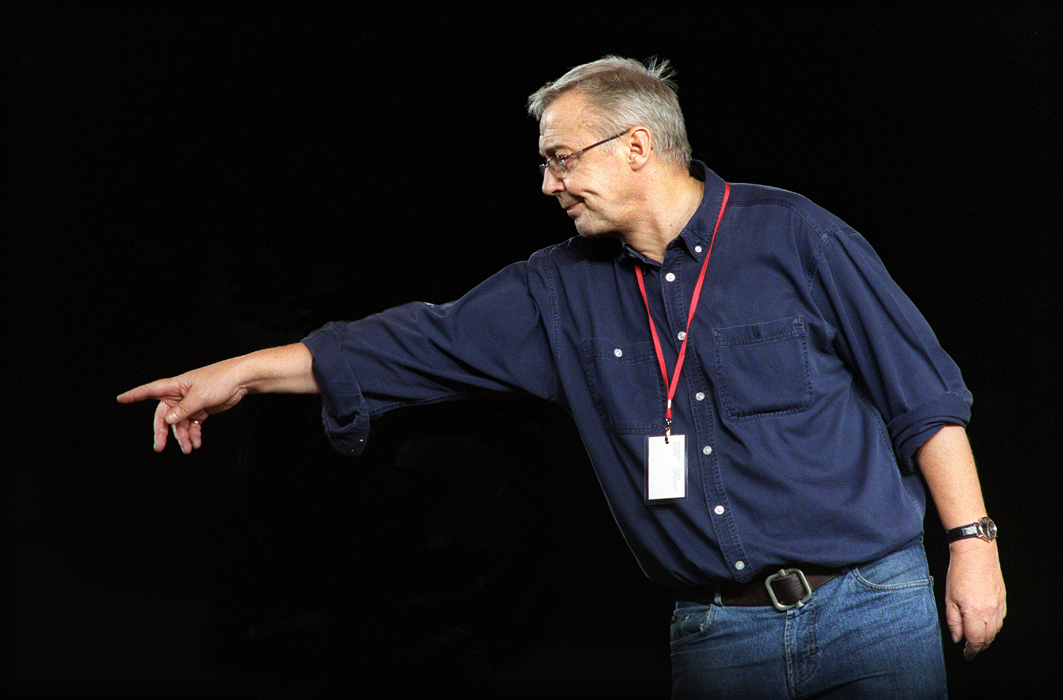

We rejoiced in huge teas at the Midland Hotel and regular Greek meals at a local Cretan restaurant. He was very warm-hearted, quick-witted and didn’t suffer fools. My work with BBC Northern Singers supported our regular use of black taxis. He taught me how important theatrical and film innovation was, from Busby Berkeley to Richard Wagner and he encouraged me to see the ENO Goodall Ring (my life changed forever).  Graham [the authoritative director of later years pictured above by Laurie Lewis] was adept at languages and very interested in productions. Very quickly he became involved in the theatrical side of life at RMCM, playing Jean, the Manservant to the Count, in a production of Strindberg’s Miss Julie. By this time Graham and I were the best of friends and I remember not recognising him at his first entrance. It was breathtaking. He was bent over, walking slowly and carefully and his face was long-suffering and contained. It was a huge achievement from someone who had little theatrical experience. Singing soon became secondary as he became assistant director to Joseph Ward in his production of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He was extremely organised and helpful in a job which rather set him apart from his peers, which he didn’t seem to mind at all. We soon realised he had a very special gift.

Graham [the authoritative director of later years pictured above by Laurie Lewis] was adept at languages and very interested in productions. Very quickly he became involved in the theatrical side of life at RMCM, playing Jean, the Manservant to the Count, in a production of Strindberg’s Miss Julie. By this time Graham and I were the best of friends and I remember not recognising him at his first entrance. It was breathtaking. He was bent over, walking slowly and carefully and his face was long-suffering and contained. It was a huge achievement from someone who had little theatrical experience. Singing soon became secondary as he became assistant director to Joseph Ward in his production of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He was extremely organised and helpful in a job which rather set him apart from his peers, which he didn’t seem to mind at all. We soon realised he had a very special gift.

He then assisted Anthony Besch in The Rake’s Progress and was soon working at Scottish Opera as an assistant and later Artistic Director, bringing innovation and opera to people all over Scotland. Sadly, I never worked with him as a director, but enjoyed so many of his productions, especially the ENO Madam Butterfly, The Queen of Spades and Eugene Onegin at Glyndebourne and his Ring in Lisbon. Much of his work was the best one would ever see anywhere and his original use of using local people in casting was extraordinarily innovative. He was also the forerunner of diversity in casting in the UK.

I cannot believe he has gone. He was a towering light in our world and will never be forgotten.

Eric Greene, baritone (pictured below by Adam Fradgley as Boris in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk) When Graham first auditioned me 10 years ago, he heard in my voice the Wotan I’ve just been singing. He said to me, you’re not really using all of your voice right now, and you’re a little bit trapped in places, and I said, yes, I agree – not to appease him but because I felt all of who I was as an artist had not been realized. And in doing that, he trusted me, role after role after role. I remember being in Palermo with him, singing Donner in Rheingold and Gunter in Götterdämmerung, shortly after the first production by him I was in, and I said to him, the next time you ever do a complete Ring cycle, I want to be your Wotan! And he said, Eric, what do you think all this is for? And around one of the later rehearsals, he said, come here and sight-read this, and it was Wotan’s "Abendlich strahlt der Sonne Auge" in the final scene of Rheingold.

When Graham first auditioned me 10 years ago, he heard in my voice the Wotan I’ve just been singing. He said to me, you’re not really using all of your voice right now, and you’re a little bit trapped in places, and I said, yes, I agree – not to appease him but because I felt all of who I was as an artist had not been realized. And in doing that, he trusted me, role after role after role. I remember being in Palermo with him, singing Donner in Rheingold and Gunter in Götterdämmerung, shortly after the first production by him I was in, and I said to him, the next time you ever do a complete Ring cycle, I want to be your Wotan! And he said, Eric, what do you think all this is for? And around one of the later rehearsals, he said, come here and sight-read this, and it was Wotan’s "Abendlich strahlt der Sonne Auge" in the final scene of Rheingold.

The way he spoke to me – we have a way of saying it in the States, the way he spoken into my life – to the artist Eric was just sowing seeds that he knew either he or others would water, because the ground was already fertile. I am now seeing the fruits of those seeds that were planted by him – and by others, but we’re talking about Graham. I sit in awe and in humility, not in any other place, because things could have gone so many different ways. His gift of seeing beyond what was there isn’t something everyone has. And then being as magnificent as he was, he made you feel that you were magnificent.

I’m convinced that the template he set for involving the community in opera, to show this enlightenment, this colour on the black and white canvas of life, to never treat the volunteers as amateurs but as people with gifts they didn’t know they had, can go forward, That was another gift, of putting people together and knowing who to put with whom. You had to be there at those events, and though I didn’t realise it when I was in RhineGold, I was so focused on who I was as a character, but just to collectively to be a part of it, I think that collectively we did something that was monumental, that was necessary and it was good – I felt good about what I gave out, and I felt good about what we did as a team. I go back to the roots of who I am as a person when I encounter Birmingham Opera: the whole community bow, it’s not about “it’s your turn to take a bow”, it’s about what we did together. We all have personal achievements, but you realise that and you move on. [Pictured below by Adam Fradgley: as Aeneas to Chrystal E. Williams's Dido, Birmingham]

I remember people first saying when I came over to England and I told them I was working with Birmingham Opera and Graham Vick,"‘oh, how is he?" "Wonderful". "Oh, you didn’t know him back in the day," and they’d go through all these stories about how he was a tyrant, how they didn’t like him. There were many different responses. I’m thinking that as I have grown and lived a bit, and I’m not ancient, but I have gained some wisdom along the road, and what I have realized is that we come here gifted, full of gifts, some of us, but we don’t come with grace, which is something you learn. And he became more full of grace as he got older. So you don’t count someone’s beginnings, because you’re realizing your magnificence as you go along.

He achieved it, and I’m happy that I met him when I did. At any point in the journey it would have been a benefit to me, but to have known him through these 10 years, I am always left in awe of what he was able to get out of people, what he was able to produce in the art that he wanted to put on. I am the better artist because of knowing him, and the better person. Because every role that he trusted me with, I found a bit of myself in it. The friendship is all important, and he is also like the father of my artistic person, he’s my artistic dad. If he said “well done”, it was well done.  I remember when we started on [Jonathan Dove’s operatic adaptation of Calderón’s] Life is a Dream, that I thought I had dealt with the absence of my father in my childhood, which has parallels with the story of the protagonist, Prince Segismundo {Greene in the role pictured above by Donald Cooper with Wendy Dawn Thompson] and it was at a point in the opera when I confronted my father – sung by the fabulous [tenor] Paul Nilon. The emotions are so raw, and I’m now in the place where I’m not hiding anything of who I am as an artist, I’m letting what I have at this point out. I have a complete emotional breakdown, so much so that Graham says ”‘OK, rehearsal’s over, everyone can go”. And he left me where I was on that stage, crumpled on the ground, until I got myself together, and he says, “Eric, I want to tell you how we dealt with everything in my family”. He tells the story of a crisis, and then he says, “after it was all over, my father looked at me and said ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ “ Very English. It broke the mood. It was cathartic, it was a healing that took place.

I remember when we started on [Jonathan Dove’s operatic adaptation of Calderón’s] Life is a Dream, that I thought I had dealt with the absence of my father in my childhood, which has parallels with the story of the protagonist, Prince Segismundo {Greene in the role pictured above by Donald Cooper with Wendy Dawn Thompson] and it was at a point in the opera when I confronted my father – sung by the fabulous [tenor] Paul Nilon. The emotions are so raw, and I’m now in the place where I’m not hiding anything of who I am as an artist, I’m letting what I have at this point out. I have a complete emotional breakdown, so much so that Graham says ”‘OK, rehearsal’s over, everyone can go”. And he left me where I was on that stage, crumpled on the ground, until I got myself together, and he says, “Eric, I want to tell you how we dealt with everything in my family”. He tells the story of a crisis, and then he says, “after it was all over, my father looked at me and said ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’ “ Very English. It broke the mood. It was cathartic, it was a healing that took place.

I won’t say he was divine, and gave me these roles thinking “he needs it”, but everything we dealt with in the story, I’m dealing with now, or elements of it. I cannot say thank you to him enough, which I have done, so if I never speak about him in a public setting, he knows, I had the chance to talk to him after Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, for the two roles I sang in it – to have the gauge of singing full throttle as Boris and to come back and sing an elegant Old Convict, foreshadowing Wotan, to thank him for that and for opening the doors that mean I can write on my CV that I’m an international opera singer.

William Lacey, conductor

It was an incredible evening, which has stuck with me ever since. The singing was the best I had ever experienced live: Bryn Terfel was Figaro, Anthony Michaels-Moore was Almaviva, and Joan Rogers was the Countess. The superb conductor was Paul Daniel. Above all, Graham Vick’s production was completely perfect: wit, humanity, insight, humour, and intensity were all balanced in a fashion that was, simply, Mozartian. It was the most compelling thing I had ever seen and heard. In the final act, where the characters are supposed to grope around in the dark, Vick conjured a stroke of genius: the lights were on. We could see everything; but the characters could not see us, or each other. It was pure delight. At the end, when the Count asked his wife to forgive him once more with feeling, the tears were streaming down my face, and I was already a lifelong devotee of Mozart, and of Vick.

Seven years later, Paul Daniel took a chance on me. I was a cocky young lad, rather too freshly out of Cambridge: gifted, probably; inexperienced, definitely; full-of-himself, without a doubt. Anyway, I was appointed Paul’s assistant conductor for The Tales of Hoffmann at ENO, and Graham Vick was to be the director. Thus, during the staging rehearsals, I got to know the man himself. A supernova of limitless energy, he seemed always to be the first person to enter the rehearsal room, and the last to leave it. While we mortals took a coffee break, he carried on working. He knew everybody’s names, from the stagehands to the chorus members. He knew every edition of the opera, which in Hoffmann is really saying something. Plus, he really knew the music: he was not merely familiar with the melodic contours of the opera; he actually knew it. He knew the inner workings of the music, in the way that a good conductor knows it. He knew what it meant when one chord shaded into another, and when a subtle transition or inflection occurred in the score. Over my subsequent twenty-two years conducting opera, I only met two other stage directors who could read, hear and grasp a musical score as completely as Graham (and here’s a clue as to their identity: they happen to be twin brothers). It was a truly exceptional gift.

At the end of the Hoffmann run Lotfi Mansouri offered me a job in San Francisco, where I became assistant to the great Donald Runnicles (who much later developed an artistic friendship with Graham, resulting in several famous productions at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin). Four years later, I returned to Europe, having learnt forty operas and gained plenty of routine and experience in the USA. The first gig I got on my return came from Graham: Fidelio in Birmingham. There, Graham taught me an extremely important lesson. He challenged me really to engage with the material: not merely to replicate the admirable performances of the past, but to investigate the score in a fresh and open-minded manner.

Graham also challenged me to question why we even bother performing operas at all. In Birmingham, he made a compelling case for the timeless relevance of Beethoven’s only opera. A piece which can seem somewhat stilted in the theatre was made completely vibrant and essential in a big top in Aston. I will never forget the sensation of conducting the Act I finale as the prisoners emerged into the light of day, under my feet. I could scarcely hear their voices from where I was standing, but I could certainly feel them. Fidelio was a wonderful meeting of minds between Beethoven and Vick: in their unique ways, they both expressed an intense love of humanity.

Another significance of the Fidelio experience for me was that I worked for the first time with some of the stalwart artists of Graham’s Birmingham productions: wonderful talents like Keel Watson, Ronald Samm and Donna Bateman. I also learnt that, in Birmingham, Graham had essentially invented a new way of doing opera, whose hallmarks were participation and proximity. Whether as an audience-member or as a participant, I found that the zesty intensity of those productions was truly unique. It could never be recaptured in a conventional opera house, with a professional chorus and professional dancers. [Pictured below: Graham Vick with William Lacey on the right].

Another four years passed, and I found myself back in Birmingham once again, for Mozart’s Don Giovanni, ossia He Had it Coming in 2006. Graham and Sarah Playfair had assembled a splendid cast. A dilapidated bank in central Birmingham was commandeered, and provided the ideal backdrop of decadent capitalism. I had enormous fun trying to figure out the monstrously complex triplicate dance routine in the Act I finale with Ron Howell, who (as so often) succeeded in providing the perfect choreographic complement to Graham’s imagination. Of the five Don Giovanni productions I have conducted, this one was easily the most vivid, the most original, and the most true to Mozart’s vision. It was very dark, and very funny.

Another four years passed, and I found myself back in Birmingham once again, for Mozart’s Don Giovanni, ossia He Had it Coming in 2006. Graham and Sarah Playfair had assembled a splendid cast. A dilapidated bank in central Birmingham was commandeered, and provided the ideal backdrop of decadent capitalism. I had enormous fun trying to figure out the monstrously complex triplicate dance routine in the Act I finale with Ron Howell, who (as so often) succeeded in providing the perfect choreographic complement to Graham’s imagination. Of the five Don Giovanni productions I have conducted, this one was easily the most vivid, the most original, and the most true to Mozart’s vision. It was very dark, and very funny.

I also remember that show for a personal reason. Early on in rehearsals, I asked Graham if I could leave on a certain date to go to my oldest friend’s wedding in Kenya. He said that, unfortunately, we would have too much work to do, and it was not a good moment: a decision which I accepted without hesitation (as a boss, Graham was always firm but fair). A few weeks later, after an especially productive week, he said to me on a Thursday evening,: "wasn’t it your friend’s wedding on Saturday? Well, we’re making good progress, I think you should go; have fun, and see you on Monday!" I legged it to Heathrow, and spent an amazing weekend in Africa.

The morning after the last Don Giovanni performance, we were both back at Heathrow, for a flight to Houston, Texas. I am certainly not bitter when I recall that Graham and Ron were in first class and I was in cattle class: they deserved it much more than me! The following day, we were in rehearsals for Monteverdi’s The Coronation of Poppea at Houston Grand Opera. This was the first occasion that I was able to experience Graham’s famous command of the Italian language. Of the many languages he spoke, he seemed to relish Italian the most. The staging rehearsals and musical rehearsals merged into one, as Graham imparted his perfect command of Monteverdian declamation to an all-star cast, including Susan Graham, Frederica von Stade, Bill Burden, Nathan Gunn, Heidi Stober, Norman Reinhardt and Ryan McKinny.

Two years later, we reconvened in Birmingham. The occasion was one of my very favourite operas: Mozart’s Idomeneo. This took place in a huge industrial building (the Sherbourne Rubber Factory), and Graham gave me the serious challenge of conducting much of it while several hundred metres away from the singers. I took this as a compliment, and did my best to make it work. Graham’s engagement with the chorus and actors was magnificent: the People of Birmingham were convincingly transformed into the People of Crete. My abiding memory of that production is of turning around to conduct the huge group standing behind me, in one of Mozart’s greatest and most tragic choruses, " O voto tremendo", and seeing Graham in amongst them, singing every note and word with tremendous emotion and commitment.

In 2012, we were back in Birmingham for the first performance of Jonathan Dove’s underrated masterpiece Life is a Dream. Graham had commissioned it for Birmingham, continuing his policy of presenting only the best operas there, be they four centuries old or four weeks old. It was an important time for me personally: one night I went to bed after a rehearsal, only to be awoken shortly after midnight with the news that my wife Claudia Huckle was in labour in Exeter. I drove down the M5 at top speed and arrived in time to greet Mathilde’s entrance into the world. A few weeks later, she attended her first opera, and experienced the splendid Segismundo of Eric Greene.  Two years later, I was back in Birmingham yet again - but this time as an audience member. Claudia was singing Marfa in Khovanskygate, while pregnant with our second child, Constanze. Graham was magnificent, both as an artist and as a Mensch. He correctly guessed that Claudia was pregnant, before she had told anyone except me, and was wonderfully supportive and empathetic during the rehearsals. The resulting production was one of the most moving performances I have ever experienced: one of the greatest of all operas, in a production that did full justice to its richness and strangeness [pictured above by Donald Cooper: Joseph Guyton and Eric Greene as the Khovanskys].

Two years later, I was back in Birmingham yet again - but this time as an audience member. Claudia was singing Marfa in Khovanskygate, while pregnant with our second child, Constanze. Graham was magnificent, both as an artist and as a Mensch. He correctly guessed that Claudia was pregnant, before she had told anyone except me, and was wonderfully supportive and empathetic during the rehearsals. The resulting production was one of the most moving performances I have ever experienced: one of the greatest of all operas, in a production that did full justice to its richness and strangeness [pictured above by Donald Cooper: Joseph Guyton and Eric Greene as the Khovanskys].

Now it’s August 2021. The arts have suffered so much already, for the last 18 months, but for me this is the lowest point of the pandemic. I am finding it very hard to accept that Graham is gone. For several hours after reading about Graham’s death on the internet, I insisted that it was fake news; eventually I started to accept that it really was true. Graham was a wonderful person, director, musician, boss, mentor and friend. I will miss him very very much. In our household, he will never be forgotten. My heart goes out to the glorious Ron Howell; and to the glorious Birmingham Opera Company.

Sarah Playfair, casting consultant

For me, Graham was much more than a colleague - he was a personal friend to me and my family for some 45 years. We first met at English National Opera in 1975 - I was Assistant to the Controller of Planning (including casting) and he was a junior assistant director to John Copley on Der Rosenkavalier. A year or two later I bought a scruffy little house on a main road in Clapham and Graham became my first lodger, for just a few months before he went to take up a seasonal contract at Glyndebourne. From that moment on we became firm friends.

As a housemate the only brush we had was when I asked him how he would like to decorate his bedroom (bearing in mind that he would be there for only a few months and that other lodgers would follow). His choice was to cover the walls in brown wrapping paper - which I vetoed in favour of a very neutral Laura Ashley pattern. He was always keen to help around the house, though his efforts were often a bit pointless (I regularly had to redo the washing up after his willing but inefficient attempts!). But he was a joyous house companion, taking me and my family to heart - and my nephews and nieces grew up with him very much in their young lives. I well remember a cold wet winter evening when we took my then five year old niece, Tabitha, to the circus on Clapham Common, insisting on wearing her new school uniform, being carried on Graham's shoulders through a sea of mud to the big top for a wonderful show. And it was Graham who persuaded me to throw a party for my 30th birthday - a party still remembered to this day (over 44 years later) by many who were there.

We worked together again at Scottish Opera in the early 1980s under John Cox - not the easiest of times for the company but a hugely enjoyable team to work with. We achieved some challenging work against all the odds, and again I had some wonderful times with Graham - I remember a couple of terrific Hogmanays.  In the early 1990s we were both at Glyndebourne; Graham by this time was with his partner Ron (whom I had first met when we were both working on the Peter Stein Falstaff for Welsh National Opera). It was wonderful to be working together again, and, in particular, Graham’s production of Eugene Onegin (with Ron’s choreography) was one of the stand-out events of that time. [Pictured above: all five Glyndebourne Artistic Directors in 1997 - Aidan Lang, Louis Langrée just taking over from Ivor Bolton - second from right - at Glyndebourne Touring Opera, with Andrew Davis in the middle and Vick on the right].

In the early 1990s we were both at Glyndebourne; Graham by this time was with his partner Ron (whom I had first met when we were both working on the Peter Stein Falstaff for Welsh National Opera). It was wonderful to be working together again, and, in particular, Graham’s production of Eugene Onegin (with Ron’s choreography) was one of the stand-out events of that time. [Pictured above: all five Glyndebourne Artistic Directors in 1997 - Aidan Lang, Louis Langrée just taking over from Ivor Bolton - second from right - at Glyndebourne Touring Opera, with Andrew Davis in the middle and Vick on the right].

Later on, and well after I had left, I took my mother (by then very frail) to see Graham’s Don Giovanni at Glyndebourne - she had chosen it to be the last opera she would go to - she had seen it many times in her life and declared afterwards that this was the best production she had ever encountered, and the only one in which she had stayed awake throughout Act Two. The day after I left Glyndebourne in a rush, Graham asked me to join him at Birmingham Opera Company, an offer which I accepted joyfully and I am still working there 23 years later. This has been the job that brought us closest together, in work that allowed me to help Graham fulfil his vision of how opera can be for anyone and everyone, reflecting and involving the community, and encouraging inclusion and diversity above all. Casting with him was always exciting and full of risks - but in a way that I relished, loving being made to look outside the box, and constantly surprised by the trust that he put in my judgement. Our discussions were always fascinating - and our last production together, RhineGold, is a testament to what we could achieve and to the confidence that he gave singers to tackle new challenges. [Vick pictured above centre with Birmingham Opera "Rising Stars" Josef Guyton, vocal coach Jane Robinson, Sarah-Jane Lewis, Ross Ramgobin and Amar Muchhala].

The day after I left Glyndebourne in a rush, Graham asked me to join him at Birmingham Opera Company, an offer which I accepted joyfully and I am still working there 23 years later. This has been the job that brought us closest together, in work that allowed me to help Graham fulfil his vision of how opera can be for anyone and everyone, reflecting and involving the community, and encouraging inclusion and diversity above all. Casting with him was always exciting and full of risks - but in a way that I relished, loving being made to look outside the box, and constantly surprised by the trust that he put in my judgement. Our discussions were always fascinating - and our last production together, RhineGold, is a testament to what we could achieve and to the confidence that he gave singers to tackle new challenges. [Vick pictured above centre with Birmingham Opera "Rising Stars" Josef Guyton, vocal coach Jane Robinson, Sarah-Jane Lewis, Ross Ramgobin and Amar Muchhala].

I am missing Graham like mad - it seemed so strange that RhineGold opened without him - and I can’t believe that he will no longer be throwing me wonderful tasks such as “find me a gorgeous baritone who is capable of defenestration with aplomb” [for Life is a Dream] - which I did. Eric Greene sang Wotan for us earlier this month.

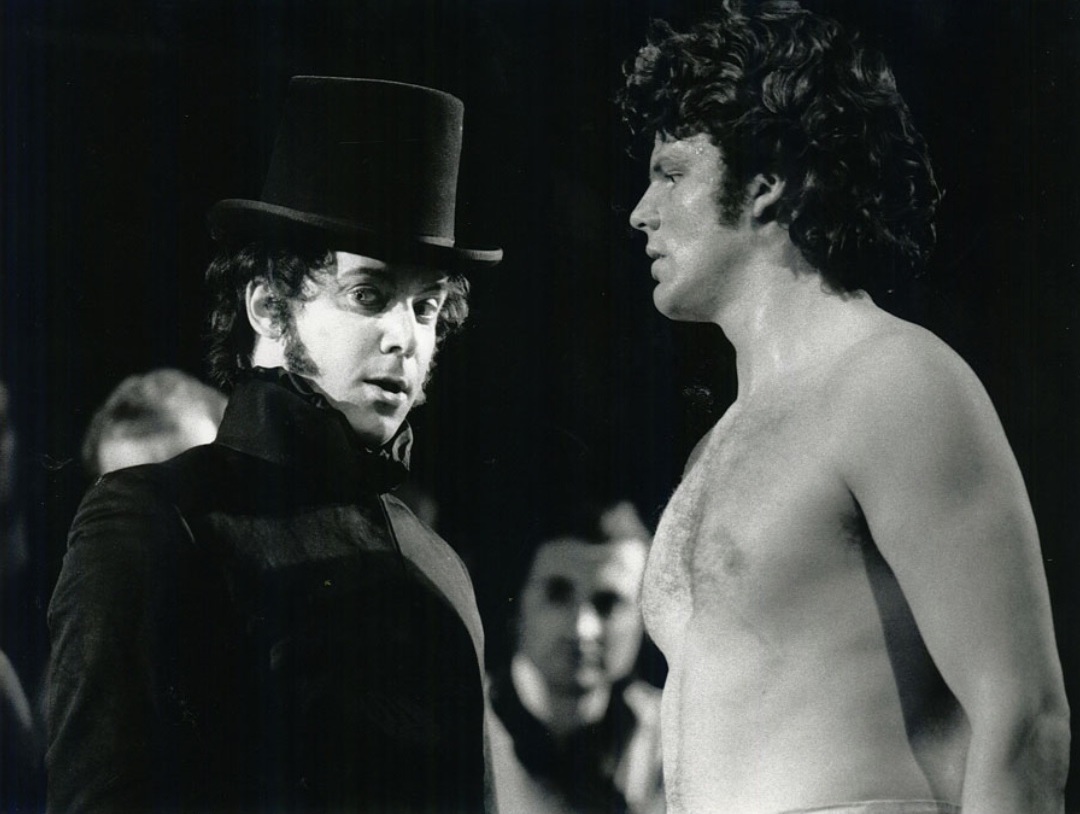

Sir John Tomlinson, bass (pictured below by Eric Thorburn as Claggart with Mark Tinkler as Billy Budd in Vick's 1987 Scottish Opera production) I wrote the following paragraph perhaps 15 years ago in a tribute to Graham’s work, and I think it gets to the centre of what it was like to be a member of the cast in one of his productions [in an earlier exchange, the bass stated that "I did at least five great, inspired productions with him which I will never forget: Billy Budd, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Pelléas et Mélisande, Moses und Aron and The Midsummer Marriage]. :

I wrote the following paragraph perhaps 15 years ago in a tribute to Graham’s work, and I think it gets to the centre of what it was like to be a member of the cast in one of his productions [in an earlier exchange, the bass stated that "I did at least five great, inspired productions with him which I will never forget: Billy Budd, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Pelléas et Mélisande, Moses und Aron and The Midsummer Marriage]. :

“Two hall-marks stand out for me, in Graham’s work: firstly, his insistence on getting into the heart of the piece, by relentless investigation; not distorting it, not even interpreting it, but being profoundly true to it. Secondly, in contrast to this meticulous detective work, the fresh creativity, freedom and excitement involved in the “journey” that follows. The results can be radical and controversial (and Graham is no stranger to controversy), the work always genuine and truthful.”

I well remember the hour’s investigation at the start of a typical day’s rehearsal with him: usually we stood around the piano, vocal scores on the piano lid, and we would begin the scene to be rehearsed that day. Probably singing to start with - a couple of phrases perhaps, and then discussion, with contributions from all sides, about everything from text and sub-text, orchestral colour, pulse, detail and all aspects of interaction between characters, our individual journeys, quirks and contradictions and seeming ambiguities, subtle implications and hollow apparent grandiose outbursts; truth or lie, wishful thinking or irrational fear? All about the quest to get to the true heart of the work before us. And then free creativity in "the space". He was an inspiration.

Chrystal E. Williams, soprano (pictured below by Adam Fradgley as The Wife in Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk)

It was a very tough process, continuing to work on RhineGold after Graham’s death; but I think we all rallied and continued the work in honour of him. We come to this company time and again because of him; and so not to have continued the work would have been a disservice, a dishonour almost, to this giant, this indomitable man who if he said it was going to happen, then that was it- it was going to happen and you were going to do it.

I think it was good that we were busy with rehearsals – it wasn’t a good situation, but if it had to happen it was better that it happened during the rehearsals leading into tech week. We did take a few days which were needed, just for people to deal with it how they could, but it was to put all that energy and everything we were feeling into something tangible that we could lift up to Graham’s memory, to Ron and the family, in support of this man who means so much to us.

It was a huge support to have so many people that I knew – it was kind of a reunion. I think that energy from us, coupled with that from the audience, helped fuel us on. You could feel it everywhere. I won’t say there weren’t moments when it was really difficult – at the end when the brass are just going at it, it was like a sendoff to Graham – I kept thinking, “Where is he? Graham should be here.” It was such a grand moment musically even, when Wotan, beautifully sung by Eric, sings about the fortress saving the gods from harm, just the text and the music- that was enough to wear on the emotions. This was my first Wagner, and I thought, wow, if the rest is like this…I wonder what all else Graham had planned in his mind for me and Wagner… [Pictured below by Andrew Fox as Fricka in RhineGold]  Graham was a great mentor, a friend, an advocate, a supporter, a musical father - my UK home. If it hadn’t been mainly for him and Sarah Playfair, my career here in the UK simply wouldn’t be. Graham made this a safe and vulnerable place for me to spread my wings and just jump. I always knew he’d catch me; while Graham always knew I’d catch myself. I remember one group zoom interview where I told him, “I believe in you, Graham.” He immediately, no hesitation whatsoever and with firm conviction, responded, “I believe in you, Chrystal.”

Graham was a great mentor, a friend, an advocate, a supporter, a musical father - my UK home. If it hadn’t been mainly for him and Sarah Playfair, my career here in the UK simply wouldn’t be. Graham made this a safe and vulnerable place for me to spread my wings and just jump. I always knew he’d catch me; while Graham always knew I’d catch myself. I remember one group zoom interview where I told him, “I believe in you, Graham.” He immediately, no hesitation whatsoever and with firm conviction, responded, “I believe in you, Chrystal.”

I auditioned for the company in 2014. I was singing Rosina in The Barber of Seville in the States, my first professional role, and I got this seemingly random email from Sarah asking for my availability and passport information – was this some kind of scam? Graham was looking for a Hannah in Tippett’s The Ice Break. It doesn’t usually happen that you get this random email asking for your passport information… I was flown to Birmingham and had my audition. Afterwards, Graham said, “Well, if it’s up to me, then you’re hired”. I thought to myself, OK, not knowing it WAS up to him, since it’s pretty much his company. Later I laughed about it, but it was one of those ethereal experiences where everything came together. It truly was meant to be. Everything lined up, including the random YouTube clip he’d seen (which I didn’t even post!) that Graham said sold him on my being his Hannah. That experience is so true to the nature of the company and to Graham’s style. I remember saying, “I have “Summertime” to sing” and he saying, I don’t want to hear that. Even Richard [Willacy] said, no, don’t offer that.  I came back in 2015 for my first role with the company and that was an experience in itself. In the States, you come to the first rehearsal in your smart clothes, expecting to present your work and with a certain expectation of being judged; whereas with Graham…well, first of all it was in this factory, where there were holes, water was dripping, it was freezing, and you could see your breath. And he had the nerve to say take off your coats-let’s warm up! And, there we were, running around in circles – I was thinking to myself, “Where am I?” But the rest is history. I jumped in and I loved it. That experience has absolutely informed how I show up to rehearsals, reminding me that first of all there’s teamwork. Graham immediately put us all on the same playing field, and that in turn created this unique space where the artist could just focus on the art - I love that.

I came back in 2015 for my first role with the company and that was an experience in itself. In the States, you come to the first rehearsal in your smart clothes, expecting to present your work and with a certain expectation of being judged; whereas with Graham…well, first of all it was in this factory, where there were holes, water was dripping, it was freezing, and you could see your breath. And he had the nerve to say take off your coats-let’s warm up! And, there we were, running around in circles – I was thinking to myself, “Where am I?” But the rest is history. I jumped in and I loved it. That experience has absolutely informed how I show up to rehearsals, reminding me that first of all there’s teamwork. Graham immediately put us all on the same playing field, and that in turn created this unique space where the artist could just focus on the art - I love that.

Graham could look at you and see and hear all of the possibilities possible in your wee vessel. And, then he was bold and daring enough to risk it all and give you a chance. He was a willful man who burst through the doors bringing with him an iron will and uncompromising vision, enough energy to charge the room for hours if not days. He believed in you and in turn made you believe in yourself.

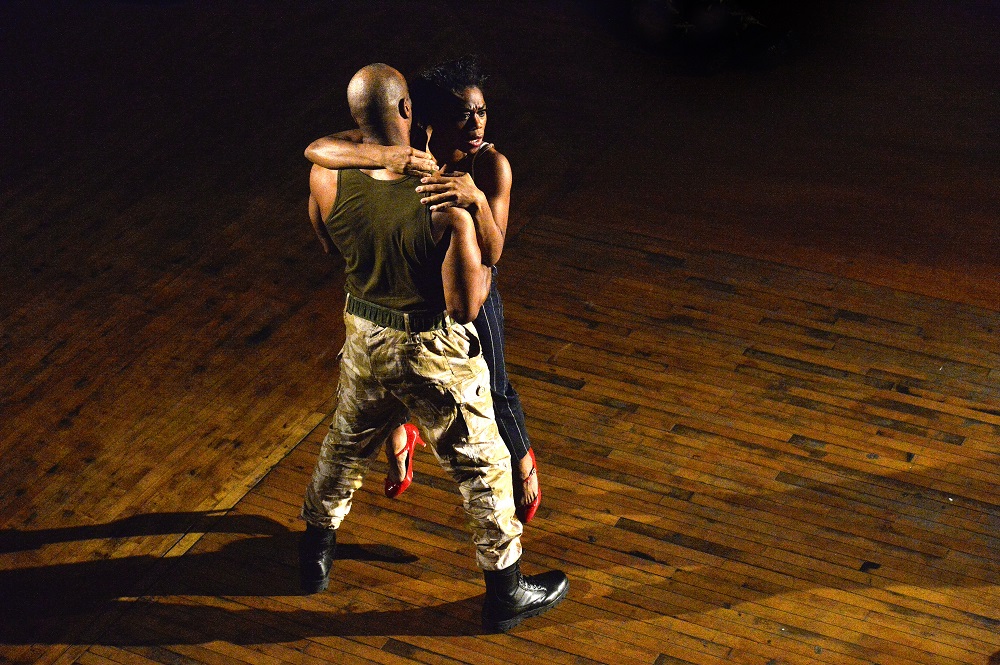

I think of how I even got here, the welcoming community, how everyone was equally important-it was this freedom. For me, as a young artist, it was my introduction to the work. It’s been monumental in how I approach things, and I honestly have not experienced it anywhere else. This is my second home. I put him in the present tense, but that’s because he’s still here. I have a strong memory of our last meeting on a zoom call for RhineGold, diving into the text. He was always about the text, making sure it was understood and communicated, and making sure we were serving the art. It’s tough to think about, but it’s also soothing – it will be a forever memory, to always go back to the text.  When Graham asked me to sing Katerina Izmailova [in Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, pictured above by Adam Fradgley with Brenden Gunnell as the lover], well, I’m a mezzo, but I’ve always been a bit of a zwischenfach (between voice types); so I said, “I don’t know, let me go and check the score.” I can sing the notes, but it’s a question of the orchestra-but, ultimately, I knew I’d do it. I always trusted him. Graham was honest and ready to say when something just wasn’t good-including from himself. He was unafraid to then start all over again ‘to get it right’. He was highly intelligent. He knew just what each of us needed to motivate us to do and be better. And, isn’t this just like Graham, even in death, to push us and dare us and force us to go on and do better and figure it out ourselves; still encouraging us to dig deeper for what he always knew was there.

When Graham asked me to sing Katerina Izmailova [in Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, pictured above by Adam Fradgley with Brenden Gunnell as the lover], well, I’m a mezzo, but I’ve always been a bit of a zwischenfach (between voice types); so I said, “I don’t know, let me go and check the score.” I can sing the notes, but it’s a question of the orchestra-but, ultimately, I knew I’d do it. I always trusted him. Graham was honest and ready to say when something just wasn’t good-including from himself. He was unafraid to then start all over again ‘to get it right’. He was highly intelligent. He knew just what each of us needed to motivate us to do and be better. And, isn’t this just like Graham, even in death, to push us and dare us and force us to go on and do better and figure it out ourselves; still encouraging us to dig deeper for what he always knew was there.

Whenever I think of the UK, of Birmingham, of the Birmingham Opera Company-I will think of Graham; see and hear and feel Graham. I love him and will miss him terribly. There is comfort in knowing that his work, his vision, lives on in and through us. I feel the company could and should drive on; because the heart and the vision, so long as you stay true to that and you have people in charge maintaining that-there’s no reason why this community, this vision and this visionary shouldn’t live on through the work.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Comments

Graham was a really special

Thanks for this, Lawson. The

Thanks for this, Lawson. The more individual memories the better.