Measure for Measure, Sam Wanamaker Theatre review - this problem play is a delight | reviews, news & interviews

Measure for Measure, Sam Wanamaker Theatre review - this problem play is a delight

Measure for Measure, Sam Wanamaker Theatre review - this problem play is a delight

Blanche McIntyre regenders the Duke and relishes the London low-life

Measure for Measure may be the quintessential Shakespeare “problem” play, but just what has earned it that epithet remains a puzzle. Each generation approaches the matter from its own perspective. The developments of recent years, #MeToo most of all, have given new resonance to one of its central themes, the imbalance of law over nature and the quality of justice, but the play’s “resolution”, if it can even be called that, leaves the questions open.

Or is it the imbalance – “balance”, as the title itself makes clear, being a key concept – between tragedy and comedy, between the deathly serious central dilemma that confronts Isabella and the bawdy comedy that runs alongside it? Blanche McIntyre’s new production in this most classic of all Shakespearean spaces transposes the action to mid-Seventies Britain, and in doing so consciously heightens that contrast. We relate to its low-life characters through a recognisable prism, with some early comic antics that could be out of the Carry On films; it’s not only the hair-dos that will have you thinking of Barbara Windsor or Mollie Sugden. This relocation in period fits in with the play’s background of social unrest, too, though while much has been made of this being a time of power cuts, which gives the candle lighting that is the Wanamaker’s trademark a new relevance too, that ends up as little more than an engaging touch for the production’s opening moments. (Pictured below, Georgia Landers as Isabella)

McIntyre’s real subversion, however, is to cast Hattie Ladbury in the central role of the Duke, here presumably Vincentia, a gender reversal that brings a range of revelations with it. And such revelation really is welcome, because the main problem with Measure for Measure remains the Duke, this figure of indisputable public authority so keen to evade the limelight (his “I love the people/But do not like to stage me to their eyes” a hint ahead towards Coriolanus?). The character’s most evident delight lies in the often cruel craft with which (s)he manipulates the main players. The part surely harks forward to The Tempest’s Prospero (a role more frequently gender-reversed), and there are a number of moments in McIntyre’s production when Ladbury – alone, stage-front, whether as Duke or in disguise as the Friar – feels she really might be Shakespeare’s final magus (main picture). But Prospero has the magic, and is bowing out, while Vincentio, relying on human means, returns to pick up the reins.

McIntyre’s real subversion, however, is to cast Hattie Ladbury in the central role of the Duke, here presumably Vincentia, a gender reversal that brings a range of revelations with it. And such revelation really is welcome, because the main problem with Measure for Measure remains the Duke, this figure of indisputable public authority so keen to evade the limelight (his “I love the people/But do not like to stage me to their eyes” a hint ahead towards Coriolanus?). The character’s most evident delight lies in the often cruel craft with which (s)he manipulates the main players. The part surely harks forward to The Tempest’s Prospero (a role more frequently gender-reversed), and there are a number of moments in McIntyre’s production when Ladbury – alone, stage-front, whether as Duke or in disguise as the Friar – feels she really might be Shakespeare’s final magus (main picture). But Prospero has the magic, and is bowing out, while Vincentio, relying on human means, returns to pick up the reins.

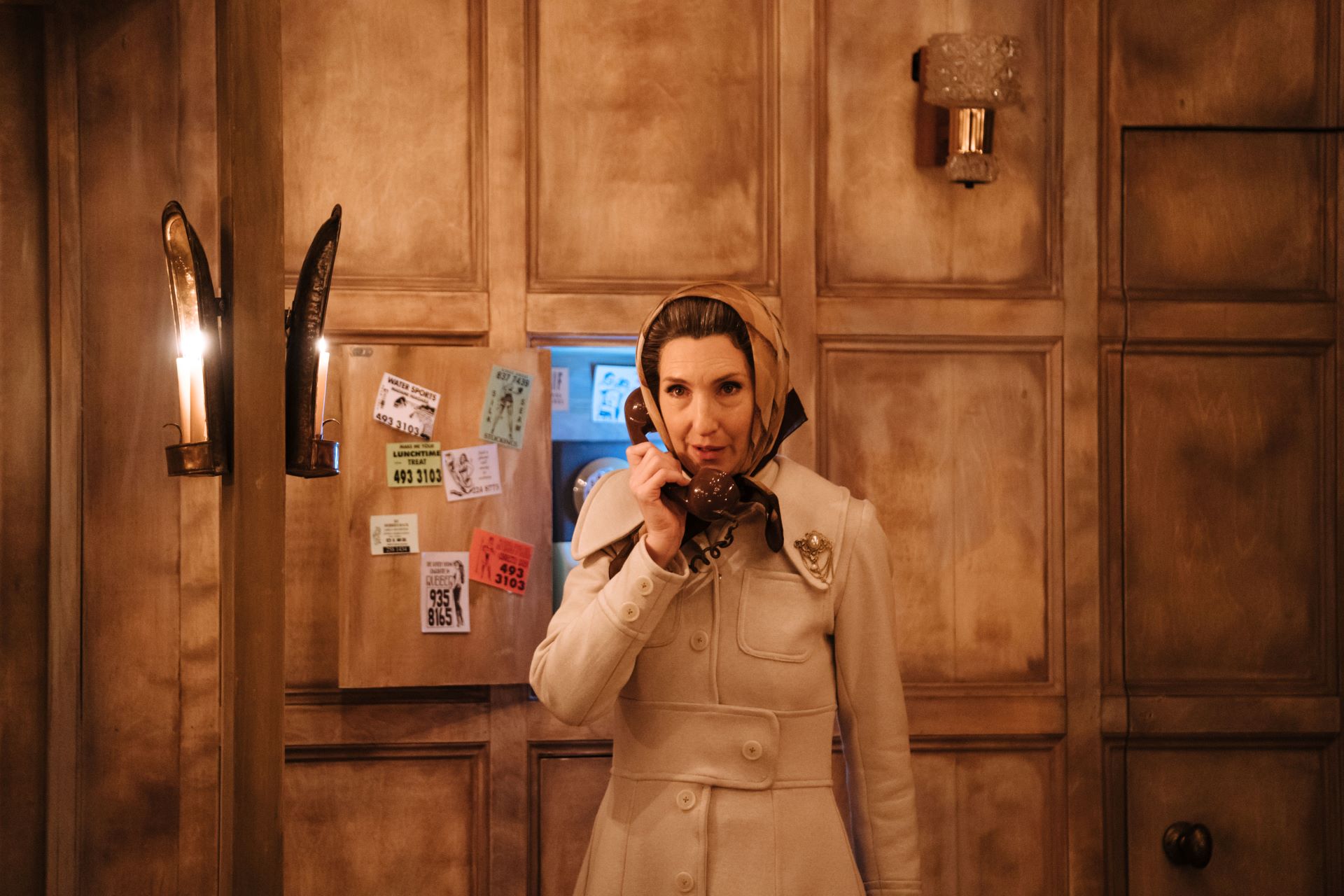

Ladbury’s interpretation of this “fantastical duke of dark corners” unpacks layers of character, not least in the modulations of delivery. Her speech in the court scenes has a mannered majesty, a fragile, even frigid diction which can silence the stage in a moment; then, the moment the court is left behind, she’s speaking from a public phone box with a careless aristo lilt (pictured below, the scene has a sense of strikingly right period, that headscarf thankfully never overplayed to emphasise real-life royal parallels). This Duke – “one that, above all other strifes, contended especially to know herself”, as Escalus recalls – has escaped for private motives every bit as much as to examine her fiefdom from a place of anonymity. In McIntyre’s interpretation, the Duke’s surprising final proposal to Isabella becomes inescapably Sapphic, which also chimes with the changing times in which the production is set. (After the male brutality of Ashley Zhangazha’s Angelo, whose delivery epitomises the cold, broken-up style of the court, it's an ultimatum that can't but feel a little gentler.) Gender reversal can’t help bringing small textual shortcomings – the pronouns with which the Duke is addressed are moderated to “she”, while titles, Duke or Prince, remain male – but there’s a new felicity to the closing interchange with the braggadocio Lucio (the Duke’s “I never heard the absent Duke much detected for women; he was not inclined that way”, answered by the latter’s “O, sir, you are deceived”).

In McIntyre’s interpretation, the Duke’s surprising final proposal to Isabella becomes inescapably Sapphic, which also chimes with the changing times in which the production is set. (After the male brutality of Ashley Zhangazha’s Angelo, whose delivery epitomises the cold, broken-up style of the court, it's an ultimatum that can't but feel a little gentler.) Gender reversal can’t help bringing small textual shortcomings – the pronouns with which the Duke is addressed are moderated to “she”, while titles, Duke or Prince, remain male – but there’s a new felicity to the closing interchange with the braggadocio Lucio (the Duke’s “I never heard the absent Duke much detected for women; he was not inclined that way”, answered by the latter’s “O, sir, you are deceived”).

It’s a re-interpretation that makes us think, one that works because it leaves the greater part to nuance, rather than forcing the details. From the other “serious” parts, I’m not certain that Zhangazha fully mines the depths of Angelo, though his self-examination is so brief anyway (and does Angelo always come across as a manqué Iago, that embodiment of evil from almost exactly the same moment in Shakespeare’s career?). Georgia Landers as Isabella has the innocent power that the role demands, though perhaps her exchanges with brother Claudio (Josh Zaré) don’t yet achieve their full impact. For sheer innocence, the cameo appearance of Juliet, played by the multi-tasking Eloise Secker, feels unmatched. It would be interesting to see the two swap roles, not least because Secker also plays Mariana, whose incarnation is a world away from the type that has come down to us from Tennyson and Millais, her “moated grange” being a place of cocktails and lounge pop on the gramophone. The sheer aplomb of that reversal of expectations is winning.

Multi-tasking is the name of McIntyre’s game, in fact, with the ever-resourceful Secker also playing the spiv Pompey with a wink-wink insouciance that is equally engaging. Supported by a live band (composer, Tim Sutton), this cast of just eight doubles (and triples) parts with such prodigious energy that it’s hard to know whether the ultimate accolade goes to Secker or to Ishia Bennison, who’s serious as Escalus, spirited as Mistress Overdone, and show-stealing in her cameo appearance as the dipso prisoner Barnadine. Daniel Millar follows those two closely, alternating between the diligent police inspector Provost and the ludicrous beat-bobby Elbow. Gyuri Sarossy’s Lucio is his own one-man band in a role that must be tricky to update – maybe the concept of the “fantastic” eventually made its way into music hall – but his speedy engagement carries all before it.

Multi-tasking is the name of McIntyre’s game, in fact, with the ever-resourceful Secker also playing the spiv Pompey with a wink-wink insouciance that is equally engaging. Supported by a live band (composer, Tim Sutton), this cast of just eight doubles (and triples) parts with such prodigious energy that it’s hard to know whether the ultimate accolade goes to Secker or to Ishia Bennison, who’s serious as Escalus, spirited as Mistress Overdone, and show-stealing in her cameo appearance as the dipso prisoner Barnadine. Daniel Millar follows those two closely, alternating between the diligent police inspector Provost and the ludicrous beat-bobby Elbow. Gyuri Sarossy’s Lucio is his own one-man band in a role that must be tricky to update – maybe the concept of the “fantastic” eventually made its way into music hall – but his speedy engagement carries all before it.

The final question is whether the balance holds between that energy and the character-driven drama around the Duke and Isabella. It does, resoundingly, though the one thing missing here is any sense of this being hierarchic Vienna. McIntyre gives us instead small-time London, a snapshot capturing the spectrum from harassed magistrates to low-life chancers (pictured above, Ishia Bennison as Escalus, Ashley Zhangazha as Angelo). Shakespeare was writing this London not with the relative naturalism of the Eastcheap scenes from Henry IV, but with a rambunctious drive that feels closer to Merry Wives. That this Measure for Measure can come across with such a degree of delight, while its moral issues retain their gravity, may be exactly what makes it a problem play, after all.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Add comment