'How that music was created remains to me a complete mystery': John Tomlinson on fellow Lancastrian Harrison Birtwistle | reviews, news & interviews

'How that music was created remains to me a complete mystery': John Tomlinson on fellow Lancastrian Harrison Birtwistle

'How that music was created remains to me a complete mystery': John Tomlinson on fellow Lancastrian Harrison Birtwistle

The great bass remembers the composer who wrote two roles with his voice in mind

It has been a difficult couple of years for us in the world of opera, losing several of our most respected and admired colleagues who have inspired us over several decades.

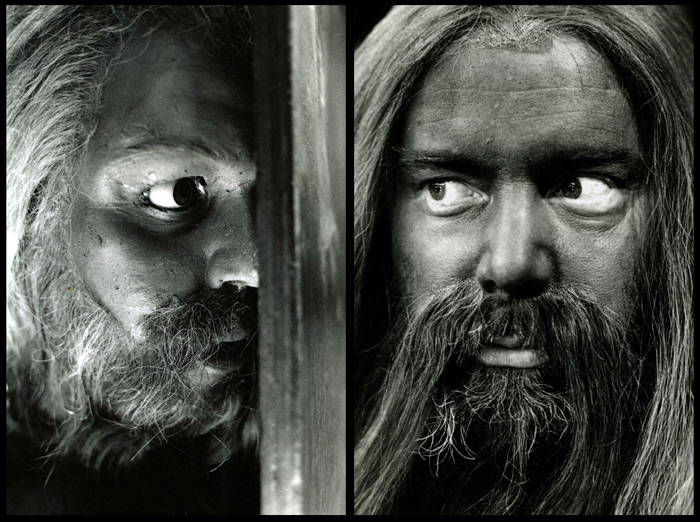

We were actually born in the same place, though twelve years apart; the same building in fact: the Rough Lea Nursing Home in Accrington, Lancashire. We were both brought up within a couple of miles of Accrington, he in Huncoat (fixed in my memory by its proximity to a huge coal burning power station), and I in Oswaldtwistle (the name always raises a smile), and we both attended Accrington Grammar School and later on the Royal Manchester College of Music. Harry had many a tale to tell about his adolescent clarinet playing days in the lively Lancashire amateur music making scene; he was rather non-communicative about his time at the grammar school; and then of course his formative years at the college as a composer with Goehr, Ogden, Howarth, Maxwell-Davies inter alia have been well documented.  I suppose, partly because we came from the same Lancashire working class musical background, that it was always comfortably natural and enjoyable being in his company, and I regret now that I didn’t see that much of him between our operatic collaborations; the Lancashire potato pie that he promised to cook were I to knock on his door sadly never saw the light of day, and it was at restaurant tables between rehearsals for Gawain in Salzburg as late as 2013 when I spent most time with him. In that year the festival was celebrating his work, and there were several memorable concerts, though our Gawain production in the Felsenreitschule had its problems and Harry ruefully thought it a “wasted opportunity”. Bearing in mind the fact that his epic operas, making as they do great demands in their orchestral and theatrical complexity, are rare events particularly outside England, I shared his frustration - although his music came through unscathed, as incisive, mysterious, fascinating, compelling as ever {pictured above: Tomlinson as the Green Knight for the Royal Opera on the right, on the left on the right that is actually me. On the left, as the author explains, is "the robotic decapitated head whose mouth and eyes move while the decapitated body holds it by the hair, while its voice comes from me in a hidden position". Diptych by David Secombe, by kind permission of the photographer].

I suppose, partly because we came from the same Lancashire working class musical background, that it was always comfortably natural and enjoyable being in his company, and I regret now that I didn’t see that much of him between our operatic collaborations; the Lancashire potato pie that he promised to cook were I to knock on his door sadly never saw the light of day, and it was at restaurant tables between rehearsals for Gawain in Salzburg as late as 2013 when I spent most time with him. In that year the festival was celebrating his work, and there were several memorable concerts, though our Gawain production in the Felsenreitschule had its problems and Harry ruefully thought it a “wasted opportunity”. Bearing in mind the fact that his epic operas, making as they do great demands in their orchestral and theatrical complexity, are rare events particularly outside England, I shared his frustration - although his music came through unscathed, as incisive, mysterious, fascinating, compelling as ever {pictured above: Tomlinson as the Green Knight for the Royal Opera on the right, on the left on the right that is actually me. On the left, as the author explains, is "the robotic decapitated head whose mouth and eyes move while the decapitated body holds it by the hair, while its voice comes from me in a hidden position". Diptych by David Secombe, by kind permission of the photographer].

His is indeed extraordinary music. I was quoted recently as having said “to sing Harry’s music is like a religious experience - you have to give yourself over to it”, and that feeling of having to allow yourself to be totally immersed in it as you perform it remains clearly in my memory. Some scenes in particular are musically overwhelming, more drowning than total immersion: Gawain’s arrival at the Green Chapel where he fears he will die is a case in point. It’s as if the heavens open as does the earth, as the cataclysm approaches. The earth spins off its axis. From such sublime chaos to ridiculous jocularity, Harry was totally at home in the theatrical world. He loved the magic of it, the illusory possibilities of it, how it can be obviously unreal but absolutely convincing, absurd but profoundly true (pictured below by Bill Cooper: Tomlinson as the Minotaur with the Innocents and Christine Rice as Ariadne, top right, in the Royal Opera revival).  Repetitive ritual, trickery with space and time – I’m reminded of Gurnemanz: “zum Raum wird hier die Zeit!” – and I remember Harry in 1998 coming to hear the Royal Opera Parsifal in concert at the Festival Hall when the theatre was closed. “ Well, it’s not actually one of my favourite pieces” he said, as ever honest to a fault; and then “I’ve got this new opera in mind: Theseus in the labyrinth, the Minotaur . . . .”

Repetitive ritual, trickery with space and time – I’m reminded of Gurnemanz: “zum Raum wird hier die Zeit!” – and I remember Harry in 1998 coming to hear the Royal Opera Parsifal in concert at the Festival Hall when the theatre was closed. “ Well, it’s not actually one of my favourite pieces” he said, as ever honest to a fault; and then “I’ve got this new opera in mind: Theseus in the labyrinth, the Minotaur . . . .”

I remember way back in 1976 working on Punch and Judy, when we made the first recording of that crazy thrilling piece in the then Decca studios in West Hampstead (these days ENO’s rehearsal rooms). That was when I first had the pleasure of meeting Harry, and enjoying his pithy comments on our singing of the text. Or SinGinG as he would have it, with percussive G’s and plain northern I’s. In conversation he was always striving to be clear, precise in meaning, economical with text, trying to hit the nail on the head, even when discussing difficult concepts. I remember a short speech he made in receiving an award for Gawain and the Green Knight, probably in 1991. It focussed on the word “art’” as opposed to the words “artefact” and “artifice”, and was impressive in its absolute clarity about what “art” meant to him. I hesitate to elucidate further, but a conversation between Harry and Tom Service on the radio, speaking of the recognisability of all oak leaves, but the uniqueness of each particular oak leaf, was another valiant attempt to explain his creative process. I must confess that, although I feel intimately connected to the music of the Green Knight and the Minotaur, roles written with my voice in mind, how that music was created remains to me a complete mystery (pictured below: bass and composer with the cake celebrating Tomlinson's 35 years at the Royal Opera).

“Ride North” was the instruction of the Green Knight to Gawain as he sent him on his journey, and I think there was some northern influence in the writing of the piece. In contrast to the “artifice” of Arthur’s court, the Green Knight has iron-clad words and striding arpeggios, and Bertilac (as the metaphysical Green Knight in human form) strikes a no-nonsense bargain in a confident, higher, more baritonal vocal line. I remember discussions with Harry and David (Harsent, librettist) as the piece was being written, and my joy at the gut and sinew in the end result. The philosophy at the heart of the Minotaur was more agonising: the combination of beast and man. The beast cannot speak until his dying moments, and is violent but innocent; the man, guilt-ridden, speaks passionately in dreams. I remember the tortuous process of finding in theatrical hardware a practical solution to the embodiment of this divided soul. The end result, after many weeks’ discussion, and hours in the costume department, was a bull’s head made of fine metal gauze: a beast on the outside, with the man illuminated inside the bull. Harry was content: “ Yes he’s half man half beast, but in this piece, he’s got to look like a bull at all times; none of this idea of having man and beast physically separate”.

“Ride North” was the instruction of the Green Knight to Gawain as he sent him on his journey, and I think there was some northern influence in the writing of the piece. In contrast to the “artifice” of Arthur’s court, the Green Knight has iron-clad words and striding arpeggios, and Bertilac (as the metaphysical Green Knight in human form) strikes a no-nonsense bargain in a confident, higher, more baritonal vocal line. I remember discussions with Harry and David (Harsent, librettist) as the piece was being written, and my joy at the gut and sinew in the end result. The philosophy at the heart of the Minotaur was more agonising: the combination of beast and man. The beast cannot speak until his dying moments, and is violent but innocent; the man, guilt-ridden, speaks passionately in dreams. I remember the tortuous process of finding in theatrical hardware a practical solution to the embodiment of this divided soul. The end result, after many weeks’ discussion, and hours in the costume department, was a bull’s head made of fine metal gauze: a beast on the outside, with the man illuminated inside the bull. Harry was content: “ Yes he’s half man half beast, but in this piece, he’s got to look like a bull at all times; none of this idea of having man and beast physically separate”.

At our last meeting, Harry said to me: “ I’ve got an idea: Jack and the Beanstalk”. “Ah,” said I “Fee Fie Foh Fum?” “Something like that”. ‘Twas not to be.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment