Blu-ray: The Bullet Train | reviews, news & interviews

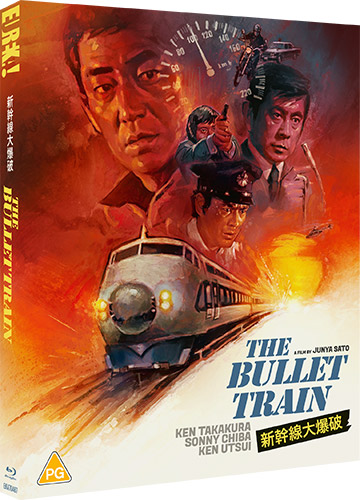

Blu-ray: The Bullet Train

Blu-ray: The Bullet Train

The 1975 Japanese action thriller that inspired 'Speed'

Last year’s Brad Pitt vehicle Bullet Train was an affable action comedy except in those parts – including the dreadful coda – when it was an insufferably smirky one. Freighted with more thrills, intelligence, gravitas, and social commentary, 1975’s The Bullet Train, released in a 2K restoration on a Eureka Classics Blu-ray, is the better movie.

Director and co-writer Jun'ya Satô’s main character is HIkari 109, a button-nosed 0-series (first-generation) Shinkansen express travelling the 1100 km between Tokyo and Hakata, a trip that then took seven hours. Seeking a $5 million pay-off, criminals have rigged it with a bomb that’ll kill the 1500 passengers if the speed falls below 80 km-per-hour; they’ll also be imperilled if excessive speed triggers the ATC command detonator.

No wonder sweat trickles down the jaw of driver Aoki, an ironically sedentary role for the popular action star Shinichi (Sonny) Chiba. “How I miss the old steam locomotive days,” he wails.

Early on, the state-of-the-art computerised railway control room is proudly presented by a documentary-like narrator as the camera roves around it. Lest the transit chief Kuramochi (Ken Utsui) and his crew doubt the bomb threat, the criminal mastermind Tetsuo Okita (Ken Takakura) has had his boys place a bomb under a goods train, which duly explodes after the engineers (who resemble World War II pilots) have leaped from the cab.

Satô couldn’t hope to sustain knife-edge tension over the film’s 152-minutes, but he took time, in any case, to develop via flashbacks (one of them an inventive montage of monochrome photos) the back stories of Okita and his two accomplices; a third is a grimacing thug (Eiji Gō) who’s been arrested and is on the train being shipped west for his trial.

The 40-year-old Okita was a businessman whose precision instrument company failed. Though not intending to kill anyone, he cynically devised his heinous get-rich-quick plot after his wife left him, taking their young son with him. Takakura, best known in the West for his performances opposite Robert Mitchum in The Yakuza (1974) and in Black Rain (1989), brings his trademark dourness to The Bullet Train but also a humanising tenderness.

The 40-year-old Okita was a businessman whose precision instrument company failed. Though not intending to kill anyone, he cynically devised his heinous get-rich-quick plot after his wife left him, taking their young son with him. Takakura, best known in the West for his performances opposite Robert Mitchum in The Yakuza (1974) and in Black Rain (1989), brings his trademark dourness to The Bullet Train but also a humanising tenderness.

It’s rare to see a villain show such compassion for his henchmen as Okita does for the loyal Hiroshi Ōshiro (Akira Odo), a kid he hired for his firm after rescuing him from the street, and the radical activist Masaru Kogu (Kei Yamamoto). Satô made these misfits likable in comparison to the railway company executives and politicians who, not untypically, are more concerned about their jobs than the endangered passengers.

Okita’s ex-wife (Masayo Utsunomiya) is also given a flashback in which she recalls the moment their marriage collapsed – her husband glibly informing her he wouldn’t be paying back the money her relatives scraped together to keep his company afloat. In another vignette, woven into the story as detectives chase their tails frantically searching for the conspirators, Kogu’s ex-girlfriend (Mitsuru Mori), hair in curlers, recounts how he sponged off her for two-and-a-half years. “He said I was taking his manhood, so he walked out on me?” she pouts. “Isn’t that horrible?”

The angry pregnant wife (Miyako Tasaka) of another feckless man is a passenger on the train. When she goes into labour owing to the stress of the journey, her agonised writhing is intercut with that of Kogu, who has been shot by the cops on his way to meet Okita.

Kogu’s plight brings home to Okita the ugliness of his crime. “We are cheap, ugly creatures. That’s what we are,” Kogu agrees in the film’s best dramatic scene, though he believes accomplishing their goal would mean they’re not ugly anymore, even if he dies. His kamikaze spirit is an element in the film’s commentary on honour and stoicism. As Okita’s main opponent and rival in cool decisiveness, Kuramochi, played with maximum restraint by Utsui, espouses grace under pressure.

Many of the supporting players overact extravagantly, which might make them seem as ridiculous as the bland musical score. But Western viewers do not necessarily appreciate how Japanese stage acting traditions filtered into movies or the tonal contrasts that are not only acceptable but expected by native audiences. The Bullet Train was a massive hit in Japan.

Satô’s direction was brisk and efficient. His use of zoom shots to emphasise revelations frequently draws attention to the camera and artificialises the action, but zooms were a common aspect of international film grammar in the 1970s, favoured in Hollywood by Robert Altman among others. Superbly orchestrated, The Bullet Train is one of the best disaster movies of its era.

The Blu-ray includes the original Japanese theatrical version and the dubbed international version; an essay by Barry Forshaw that usefully contextualises the film in Japanese studio and genre history; and an archival featurette with Satô. There's also a new audio commentary and interviews with critics Tony Rayns and Kim Newman.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Add comment