Tarik Saleh was born between two worlds, with a Swedish mum and Egyptian dad. His Egyptian side has inspired his two highest-profile releases.

Seedy, sweeping noir epic The Nile Hilton Incident (2017) followed Cairo cop Noredin (Fares Fares) as his investigation of a murder unpicks his faith in his department’s violent corruption, and the Arab Spring briefly brings that world crashing down. Now Cairo Conspiracy, a Cannes prize-winner for Best Screenplay and big hit in France, sees innocent Adam (Tawfeek Barhom) leave his fishing village to study at Cairo’s iconic Islamic university Al-Azhar. When its Grand Imam dies, Adam becomes a pawn of State Security veteran Colonel Ibrahim (Fares again) as they ruthlessly back their favoured replacement: there can’t, after all, be “two pharaohs”. The dangerous odyssey of survival taken by Tahar Rahim’s Algerian character through a French jail in A Prophet may come to mind, here transplanted to a cloistered, claustrophobic seat of learning.

Saleh reread John Le Carré’s complete works as he prepared his latest tale of subterfuge, which also considers competing ideas of Islam: a student’s transported, transcendent singing, blasphemous to some, and Marx-quoting, moral, wily Blind Sheikh Negm (Makram Khoury). As with The Nile Hilton Incident, shot in Morocco after a last-minute Egyptian filming ban, he had to do so from afar. Istanbul stands in for Cairo this time.

Saleh grew up in a working-class Stockholm suburb alongside the bank robbers who shook the city in the Nineties, making their female associates the heroes of his live-action feature debut Tommy (2014). “Film saved my life when I was a kid,” he’s said of an adolescence spent rapturously dreaming of better worlds in the auditorium dark. His anti-authoritarian streak found expression as a graffiti artist, followed by Swedish success as a TV presenter, producer, documentarian and animator; his dystopian sf cartoon Metropia (2009) involved an oppressive Europe-wide tube system and mind-bending shampoo. Following The Nile Hilton Incident, Hollywood called for The Contractor (2022), another twisting thriller, with Chris Pine and Kiefer Sutherland involved in post-Iraq War black ops.

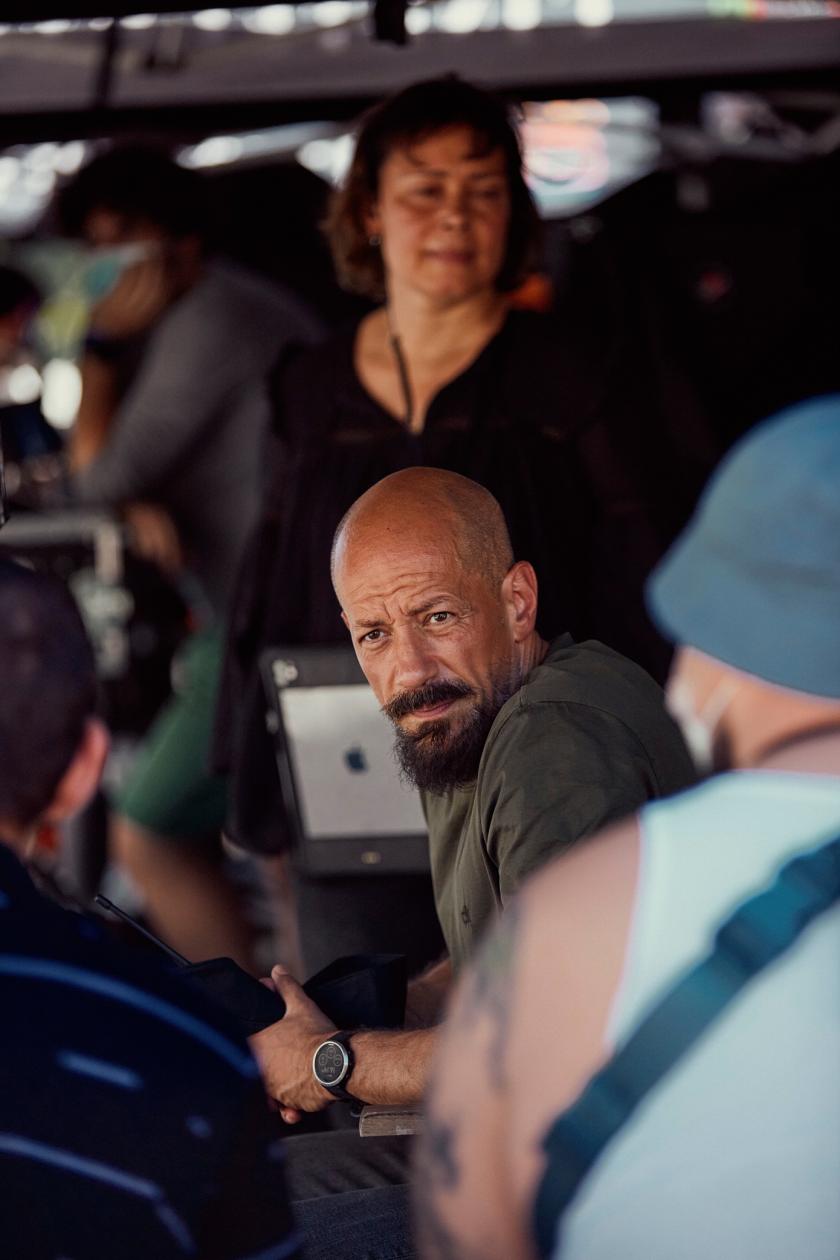

Saleh speaks to theartsdesk from his Stockholm home, holding forth on Islam, Egypt and spies at learned, discursive, enthusiastic length.

NICK HASTED: The sheer size of Al-Azhar is striking - a seething city this boy from a fishing village is thrown into. Did you find that vastness interesting?

NICK HASTED: The sheer size of Al-Azhar is striking - a seething city this boy from a fishing village is thrown into. Did you find that vastness interesting?

TARIK SALEH: Oh yeah for sure. My grandfather went to Al-Azhar and he came from a village, so it’s part of my family history. But it’s a little bit like the Vatican, it’s so big that for most Sunni Muslims it has become this expression of power that you don’t reflect over. And one luxury I have is observing Egypt and Sweden from this inside-outside perspective. So when I’m bored, I start to think about it. And one of the most interesting aspects for me is that power in Sunni Islam has a built-in conflict. Because there is no authority above God, and so every human being is equal in front of God. Your power comes from knowledge, that is the only way you can lead - which is absurd when you look at the Middle East, where that absolutely isn’t what power looks like. But Al-Azhar has become a power centre, because they have the most knowledgeable people about Sunni Islam. It has been challenged over time. In the ‘80s, this TV Imam called Sheikh Sha’rawi was popular and beloved, because he explained the Koran in colloquial Egyptian. And today it’s the YouTube Imams. So I was thinking, ‘Wow, no one has ever gone there in fiction.’ And why? It’s not a holy place. It’s a university.

Is one of the problems you show with Al-Azhar that it is a centre of power?

Yes, it’s been very interesting, as soon as I put the magnifying glass on it you see all these wrinkles, and how do you deal with that? Egypt has a history where there’s always been the pharaoh and the priest, and the relationship has always been problematic. When times have been good, the priest is declaring the pharaoh is God on earth. To take a historical parallel, [Egyptian President] el-Sissi is trying to move Cairo over the Nile, to create a new Cairo. And the last pharaoh who tried to do that was Akhenaten, who was erased from pharaonic history. In Egypt, change is not a positive word.

Did you see the Arab Spring as it played out in Cairo as part of a longer Egyptian story?

Did you see the Arab Spring as it played out in Cairo as part of a longer Egyptian story?

Oh, for sure. First of all I was swept away by it. It happened on my birthday, the 28th [January 2011]. On the 25th, I thought it was going to be a temporary thing that was going to be smashed. My father was in Egypt and I was in Stockholm and I’m calling him, but Mubarak has turned off the phones. Later that evening I get word from relatives outside Egypt, going, ‘Oh my God, it’s a real revolution!’ I got my father on a satellite phone, and he said, ‘I never thought I would live to see this, it’s incredible!’ And I refuse to be cynical about that first revolution. I think what the young people did then is as important as 1989 in Europe when the Wall fell. I know the Army and the Muslim Brotherhood and all these cynical people have hijacked the revolution in the short term, but in the long run, there’s a whole generation of Egyptians, even though they’re disillusioned or cynical, who’ve changed forever. Because they’ve seen with their own eyes that they could remove a tyrant who had an army and the police. It’s also interesting that Al-Azhar students were the last to join. You see a little bit in Cairo Conspiracy that there is this push and pull in Islam. One way to read it is to say no, you should not oppose the leader, because internal war between Muslims is a death sin. But there is this other version where Allahu Akbar – God is greater. So any human being who tries to be greater than God is an apostate. And you could argue that these tyrants are trying to be pharaohs, who in the Koran are evil enemies of God, who you’re allowed to fight with violence. So that presents a revolutionary version of Islam. This struggle has been going on inside Al-Azhar, a huge institution with 300,000 students.

And Cairo Conspiracy shows that ferment of competing intellectual schools – not a monolithic Islam.

Oh yeah. I’ve always felt like the way Islam is presented in the West serves a need to find that people on the other side are idiots and evil. But of course our leaders tell us that so we won’t protest when our freedoms are removed, because we have to protect you from this evil. Whereas I have a foot in both cultures, and I know Islamic descriptions of Sweden are also totally wrong. I’m a Muslim in Sweden, and I don’t think it should be forbidden to burn the Koran, but the majority of Swedes have more in common with a common person in Egypt or Turkey who thinks it’s offensive. I also think it’s offensive, but I think it’s okay to be offensive. Even when I was young here in Sweden and fasting with Eritreans during Ramadan, the discussion we had when we broke fast was very advanced. This was 20 years ago, and we were discussing whether it’s okay to have sex changes, which wasn’t discussed in Sweden at the time. There’ve always been these very open discussions, and criticism too. People say, ‘Is this film dangerous?’ Yes, it’s dangerous politically. But from a religious point of view, absolutely not. All Muslims know that there are corrupt Imams. Like most Christians know if you’re a paedophile, a church is a great place to hide, because you have a lot of trust in your community. It’s not so controversial. It’s of course hurtful and painful for believers to be misled.

There’s a conflict that plays out in some of your characters. In The Nile Hilton Incident, the policeman Noredin’s dad says to him, ‘You can’t buy dignity, son.’ (Fares Fares as Noredin is pictured above). And the Blind Sheikh has a similar conversation with Ibrahim. This starts seeds of morality or shame growing till they can’t live within the system, and try to break it. Are those dilemmas interesting for you?

There’s a conflict that plays out in some of your characters. In The Nile Hilton Incident, the policeman Noredin’s dad says to him, ‘You can’t buy dignity, son.’ (Fares Fares as Noredin is pictured above). And the Blind Sheikh has a similar conversation with Ibrahim. This starts seeds of morality or shame growing till they can’t live within the system, and try to break it. Are those dilemmas interesting for you?

Yes. It’s very personal to me. It’s a conversation I have with my father. He will point out to me when I’m being opportunist. He won’t let me get away with it. What he will refuse is that I’m doing it, and pretend that I’m not. He’ll say, ‘At least be honest.’ And the stakes become higher when you live in a system that is corrupt. And corrupt means utterly broken, right? The reason why Egypt is corrupt is also that it has been ruled by foreigners since forever. And that there has been an alternative system, because if you want something you can’t go to the British or Turks who are ruling you. So you create this parallel system over 1000 years that works. And then you have a national revolution, and Egyptian rulers trying to create a new system that doesn’t. Wasta, which means favour in Arabic, is a positive word. We would call it corruption. Sweden has its own much more sophisticated corruption, every society has. Egyptians are more honest about it. And that’s something I love about Egypt. There is this empty nationalism that the Army’s pumping out, but general Egyptians know exactly what they are. They have no illusions. It’s very simpatico to me. Swedes used to be like that, till these last few years of empty nationalism.

Is Cairo Conspiracy in some ways a love letter to your Egyptian family? It is partly the story of the journey your grandfather took, and you also used to be told stories about that village where he and your dad grew up. This film seems like a parable or myth you’ve added to those stories you grew up with.

Oh, absolutely. There is this folkloric myth that’s told in Egypt that people love about the simple man, the little ant, who gets underestimated, and has a special connection to God. I love that kind of folklore, most Egyptians do. And then of course there’s the myth about my own family. And it’s hard to know what is real. But there are pictures, and it’s mind-blowing to me. Especially my grandmother, her story is incredible. She was born in 1910, and convinced her parents to let her read and write – I don’t think I would be where I am if she hadn’t taken that step. It’s an individual realising that they can change everything, and paying the price, which she really did. She was a teacher in 1940s, 1950s Egypt, the time of reforms by the first [independent] education minister Tahir Hussain, who was the model for Sheikh Negm. That character mashes together Hussain, who was blind and went to Al-Azhar, which he tried to close because he thought it was backward, and the revolutionary, Marxist poet Ahmed Fouad Negm, who I had the pleasure to meet. I love Egypt. And I don’t love it in an empty patriotic way. I love Egypt because it is such a complex, human place. Cairo doesn’t give a flying shit how you perceive it. People say, ‘Yeah, I was in Cairo, I got diarrhoea, I bought false papyrus they said was real. Yeah, that’s Cairo for you.’

Is it a great sadness to you that you’ve made two great Cairo movies almost entirely outside of Cairo?

Is it a great sadness to you that you’ve made two great Cairo movies almost entirely outside of Cairo?

It’s my biggest dream to shoot in Cairo, and my obsession to recreate Egypt as I see and feel it. It’s a real sadness. But when I was thrown out of Egypt and I had to recreate The Nile Hilton Incident in Morocco, because I’m a cinema fanatic, I took comfort in knowing that Fellini shot Amarcord [his autobiographical 1973 film of his Rimini boyhood] in Rome, because he couldn’t stand going home. And that is what cinema is like, that’s why I say a director is at heart an immigrant. You don’t have to have fled your country for political reasons, but you fled for some reason. Whether you’re Kubrick, who moved from New York to England, or Coppola, who was the son of immigrants, or Milos Forman or Billy Wilder, you are a stranger. Even Lars Von Trier, a Danish director who has never been to America, recreates it in the south of Sweden in a hangar [in Dogville, 2003], and makes the most poignant portrait of America. That is cinema for me.

How do you read the look that Adam (Tawfeek Barhom, pictured above) gives when he’s asked what he learned at Al-Azhar? It’s an impenetrable, thousand-yard stare.

When I’ve finished the film, I hand it over to the audience. But having seen the film four or five times with an audience, every time I’ve read the ending differently, depending where I am in my life - if I feel hope or not. I had a very clear intention writing it of what happened at the end. But that is not relevant anymore. Because then I should have written a novel, with a text explaining what he’s thinking. But with cinema, it is that story that is told between the cinema and the audience.

Fares Fares makes such a shape-shifting transformation from his sleazy cop in The Nile Hilton Incident. Ibrahim (pictured above) looks like a shambling, harmless hippie uncle…

Fares Fares makes such a shape-shifting transformation from his sleazy cop in The Nile Hilton Incident. Ibrahim (pictured above) looks like a shambling, harmless hippie uncle…

We are very close, and he is involved early on and helps shape his characters, and there was a little bit of push and pull between us, because I said, ‘It’s too comical. You look like my grandmother!’ He had modelled it after his uncle. And he said, ‘Trust me, you will not think I’m funny at the end of this film.’ And there is a mutual trust between us which is fruitful and amazing. When we work it’s so filled with playfulness and lust, and his preparation for these roles is insane, and secretive. He doesn’t like to talk much. He asks a lot of questions during the script period. He’ll say, ‘I don’t think I care about this kid, I don’t think I’m going to try to save him. I don’t see any reason to.’ And I ask him, ‘And yet you do, so why would you?’ And he says, ‘I see something in him that I admire, a talent I think is worth saving.’

So your characters live and shift?

Oh yes. That’s the only way to make a film so that it’s fun. And also, I’m a John Le Carré fanatic, and one of the biggest challenges with this story is that I realised Smiley would never let his asset know what he’s doing. Because I feel like I know Smiley, I always think, ‘What would Smiley do, in this situation?’ I ask myself that constantly.

Do you ask that in your daily life?

Oh, 100%! The person I identify with in the film is Ibrahim, not Adam. And Smiley is definitely the character I identify with, because he finds his morality not in doing the right thing, but doing it right. He doesn’t believe in the bigger cause, he just believes in doing the job really well. Which is kind of a Nietzschean approach to life, right?

Add comment