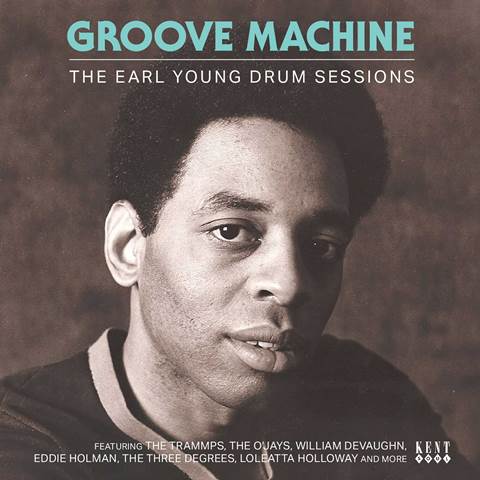

Music Reissues Weekly: Groove Machine - The Earl Young Drum Sessions | reviews, news & interviews

Music Reissues Weekly: Groove Machine - The Earl Young Drum Sessions

Music Reissues Weekly: Groove Machine - The Earl Young Drum Sessions

A deep dig into the studio musician integral to creating disco music

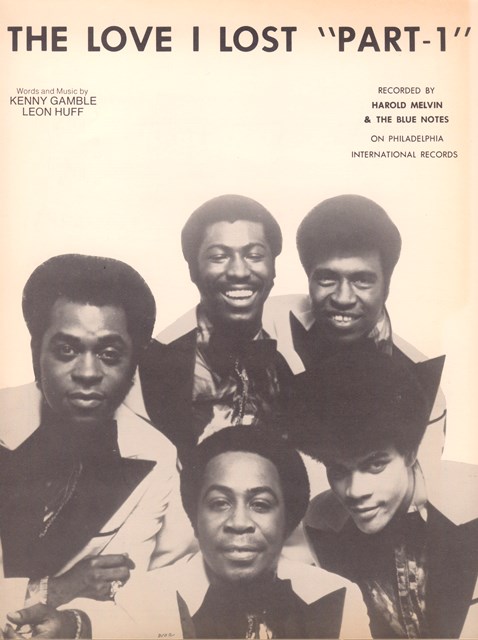

A few records changed music. One such was “The Love I Lost (Part 1)” by Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes. Issued as a single by the Philadelphia International label in August 1973, its release introduced what would become a major characteristic of disco music. This was the first time a particular groove was heard; the percussive use of the drum kit’s cymbals with an emphasis on the hi-hat.

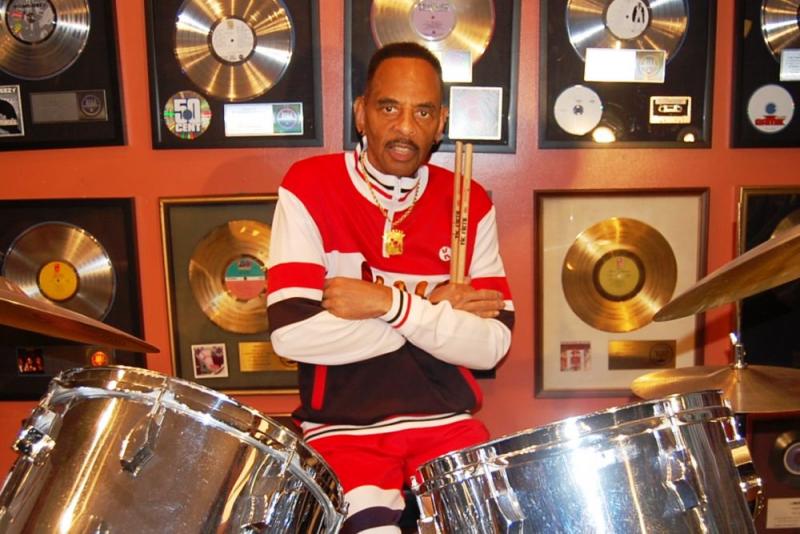

The inventor of this soon-to-be ubiquitous signifier was Earl Young, a studio-based drummer who since around Autumn 1971 was regularly booked by Philadelphia International producers and songwriters Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. As a session player on soul recordings his first bookings were in 1964, when he played on Nella Dodds’ version of The Supremes’ “Come See About me.” At this time, Young was a member of Philly band The Volcanos, whose first single was issued in 1965. A little earlier, he had been playing in the band led by sax player Sam Reed, who held a residency at Philadelphia’s Uptown Theater.

When recording with Gamble and Huff at Sigma Sound Studios, he was left to get on with it. Interviewed for the booklet coming with Groove Machine - The Earl Young Drum Sessions, Young says the duo “never had any drum parts written out for me. My job [was] to come in and lay grooves down. ‘The Love I Lost’ was a ballad at first but I made a disco beat. I said ‘Man. Come on man. I like funky stuff, let’s try this.’” And, with that – a defining component of disco music was invented.

When recording with Gamble and Huff at Sigma Sound Studios, he was left to get on with it. Interviewed for the booklet coming with Groove Machine - The Earl Young Drum Sessions, Young says the duo “never had any drum parts written out for me. My job [was] to come in and lay grooves down. ‘The Love I Lost’ was a ballad at first but I made a disco beat. I said ‘Man. Come on man. I like funky stuff, let’s try this.’” And, with that – a defining component of disco music was invented.

As the outline above indicates, Earl Young was about more than one record. His role as an innovator was spontaneous. Of course, a producer’s choice of who was booked for a studio session took account of the distinct styles they brought to bear and how the musicians slotted in to what was being recorded. But by following his musical nose, Young evolved his own style – what he dubbed his “four on the floor” style. For those with a particular kind of ears the Earl Young style is instantly recognisable, even when he was playing a session where the song didn’t ostensibly allow an individual player a chance to stamp their own personality on the record.

Take Archie Bell & The Drells’ “Do the Hand Jive” (released 1969, track three on Groove Machine). It’s a very structured record but Gamble and Huff, along with arrangers Thom Bell and Bobby Martin, decided to foreground Young’s drums: as much so as the vocals. It’s the same with the mostly Bell-helmed “Trying to Make a Fool of me” by The Delfonics (1970, track six). Without these particular drums, each record would not have been what it was.

Take Archie Bell & The Drells’ “Do the Hand Jive” (released 1969, track three on Groove Machine). It’s a very structured record but Gamble and Huff, along with arrangers Thom Bell and Bobby Martin, decided to foreground Young’s drums: as much so as the vocals. It’s the same with the mostly Bell-helmed “Trying to Make a Fool of me” by The Delfonics (1970, track six). Without these particular drums, each record would not have been what it was.

Groove Machine collects 23 tracks. The earliest is The Volcanos’ Motown-ish “Storm Warning,” a 1965 single with structural nods to The Supremes’ "Come See About me" (as noted earlier, Young had already played on a cover of the song). The cut-off comes in 1977, with the groovy single version of Loleatta Holloway’s “Hit and Run.” In between, beyond “The Love I Lost (Part 1),” the best-known cuts include The Delfonics’ “Trying to Make a Fool of me,” New York City’s “I'm Doin' Fine Now,” The O'Jays’ “Backstabbers,” The Spinners’ “Just Can't Get You Out of my Mind” and Dusty Springfield’s “Silly Silly Fool.” Earl Young was on them all, and integral to some of the greatest records ever made.

The track selection has some interesting twists. The comp opens with the 1975 Tom Moulton mix of The Trammps’ “Penguin at the Big Apple / Zing! Went the Strings Of My Heart (Medley),” with Young featured on bass voice. The version of The Three Degrees’ “The Sound of Philadelphia” is taken from an album, and was also issued as single in Japan – this version differed from what was regularly heard via TV when the song was used as the theme to Soul Train.

The track selection has some interesting twists. The comp opens with the 1975 Tom Moulton mix of The Trammps’ “Penguin at the Big Apple / Zing! Went the Strings Of My Heart (Medley),” with Young featured on bass voice. The version of The Three Degrees’ “The Sound of Philadelphia” is taken from an album, and was also issued as single in Japan – this version differed from what was regularly heard via TV when the song was used as the theme to Soul Train.

Groove Machine could function as a top-notch soul collection and, as that, it would do its job with gusto. However, it is plainly more than this. By tying together a broad and representative selection of tracks featuring Young, its story goes further than the credits on a record’s label or sleeve. Just as it was with a Motown player like Benny Benjamin or Muscle Shoals’ Roger Hawkins, it can take time for studio musicians to become as lauded as the singers of the songs hurtling up the charts, and those who arranged, produced or wrote them.

Young didn’t mind this. In the booklet, he says “When I play, it’s usually in the recording studio. That’s why other drummers don’t know me, they don’t see me playing but they know my drum sound. I like sessions only, because I like to hear myself on the radio, in malls, around the world.” Groove Machine - The Earl Young Drum Sessions will doubtless please the now 83-year-old Young. For everyone else it is a joy, from start to finish. It is also a conscientious tribute to this important musician.

- Next week: Frustration - Long Island garage-psych titans The Mystic Tide hit the shops again

- More reissue reviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Emily A. Sprague realises a Japanese dream on 'Cloud Time'

A set of live improvisations that drift in and out of real beauty

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Trio Da Kali, Milton Court review - Mali masters make the ancient new

Three supreme musicians from Bamako in transcendent mood

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Hollie Cook's 'Shy Girl' isn't heavyweight but has a summery reggae lilt

Tropical-tinted downtempo pop that's likeable if uneventful

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Pop Will Eat Itself's 'Delete Everything' is noisy but patchy

Despite unlovely production, the Eighties/Nineties unit retain rowdy ebullience

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Music Reissues Weekly: The Earlies - These Were The Earlies

Lancashire and Texas unite to fashion a 2004 landmark of modern psychedelia

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Odd times and clunking lines in 'The Life of a Showgirl' for Taylor Swift

A record this weird should be more interesting, surely

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Waylon Jennings' 'Songbird' raises this country great from the grave

The first of a trove of posthumous recordings from the 1970s and early 1980s

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Lady Gaga, The Mayhem Ball, O2 review - epic, eye-boggling and full of spirit

One of the year's most anticipated tours lives up to the hype

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

Slovenian avant-folk outfit Širom’s 'In the Wind of Night, Hard-Fallen Incantations Whisper' opens the door to inner space

Unconventional folk-based music which sounds like nothing else

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

'The Art of Loving': Olivia Dean's vulnerable and intimate second album

Neo soul Londoner's new release outgrows her debut

Music Reissues Weekly: The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Most Up Till Now

Definitive box-set celebration of the Sixties California hippie-pop band

Music Reissues Weekly: The Peanut Butter Conspiracy - The Most Up Till Now

Definitive box-set celebration of the Sixties California hippie-pop band

Add comment