MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at | reviews, news & interviews

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

MacMillan Celebrated, Royal Ballet review - out of mothballs, three vintage works to marvel at

Less-known pieces spanning the career of a great choreographer underline his greatness

Triple bills can be a difficult sell for ballet companies. Audiences prefer big sets and costumes, and a storyline they can hum. It’s not hard to see why Kenneth MacMillan’s full-evening hits Romeo and Juliet and Manon have turned out to be such a valuable legacy for his widow and daughter – companies around the world have an endless appetite for staging them.

But MacMillan’s shorter pieces have challenged the art form in a greater variety of ways. They have arguably also done more to shape the collective identity of the company that he tried several times to escape but which repeatedly drew him back like a magnet. The Royal Ballet’s latest bill offers three highly contrasted samples of that creative output, none of which has been seen for years: a piece from the start of MacMillan’s career, one from the middle and one from the end. Their sheer range of invention leaves most of today’s choreographers looking like one-trick ponies, and it’s to be hoped that next week’s cinema broadcasts will – with the benefit of up-close camerawork – underline that inventiveness in all its dazzling detail. Danses Concertantes – named after its Stravinsky score – was made in 1955 when MacMillan was just 27, an explosion of acid colours and quirky shapes (pictured above and main picture) that match the fractured structures of the music. While not being about anything, the piece has a pronounced carnival atmosphere with hints of cocktail-party glamour and the new social dances such as jive. Faces are set in profile, feet flick like knives, and knee and elbow joints work overtime with mechanical precision. Crazy speeds and tricksy, on-the-beat steps raise the odd laugh. The only let-up is a glorious pas de deux in which MacMillan’s later mastery of partnerwork is already visible in embryo as the boy swoops the girl laterally across his spine and back again, just like that. Another boy, tricked out as a hotel bellboy-cum-jester, bounces Tiggerishly in punishing forward-slash jumps before landing in the splits – from which precarious position he is hauled up by a gaggle of concerned females. Who knew the mid-Fifties were so much fun?

Danses Concertantes – named after its Stravinsky score – was made in 1955 when MacMillan was just 27, an explosion of acid colours and quirky shapes (pictured above and main picture) that match the fractured structures of the music. While not being about anything, the piece has a pronounced carnival atmosphere with hints of cocktail-party glamour and the new social dances such as jive. Faces are set in profile, feet flick like knives, and knee and elbow joints work overtime with mechanical precision. Crazy speeds and tricksy, on-the-beat steps raise the odd laugh. The only let-up is a glorious pas de deux in which MacMillan’s later mastery of partnerwork is already visible in embryo as the boy swoops the girl laterally across his spine and back again, just like that. Another boy, tricked out as a hotel bellboy-cum-jester, bounces Tiggerishly in punishing forward-slash jumps before landing in the splits – from which precarious position he is hauled up by a gaggle of concerned females. Who knew the mid-Fifties were so much fun?

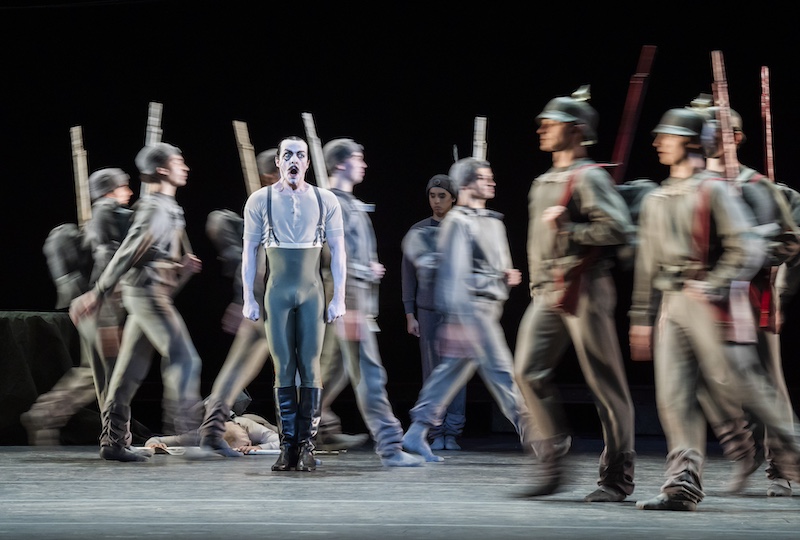

Different Drummer, MacMillan’s take on the story of Woyzeck, is anything but. Alban Berg’s opera is universally seen as the ultimate adaptation of Georg Büchner’s play about a low-ranking German soldier and his grim travails, but MacMillan’s 45-minute ballet runs it close, a result of his determination to prove that ballet was capable of presenting the full gamut of human experience, however disturbed or disturbing. His innovation was to tell the story through the eyes of its central character, who kills his lover Marie after being driven insane by the pharmaceutical meddling of military doctors. Wild expressionist imagery presents Woyzeck’s hallucinations as he experiences them: nightmares of squad-bashing and an apoplectic Captain (Thomas Whitehead, pictured above), the conviction that everyone he knows is mocking him; the conviction that his woman Marie is really in love with the priapic Drum Major; worst of all, that he is losing his mind. Music by Webern and Schönberg supports this catalogue of mental torture. At the end, as Schönberg's Transfigured Night winds to its surprisingly serene close, it's left for us to decide whether there is a chance of redemption for Woyzeck. On opening night Marcelino Sambé danced him as if his own life depended on it. He had even developed a special hunched walk, a depressed and self-protective hobble, that spoke volumes even when his back was turned to us. It was moving beyond words.

Wild expressionist imagery presents Woyzeck’s hallucinations as he experiences them: nightmares of squad-bashing and an apoplectic Captain (Thomas Whitehead, pictured above), the conviction that everyone he knows is mocking him; the conviction that his woman Marie is really in love with the priapic Drum Major; worst of all, that he is losing his mind. Music by Webern and Schönberg supports this catalogue of mental torture. At the end, as Schönberg's Transfigured Night winds to its surprisingly serene close, it's left for us to decide whether there is a chance of redemption for Woyzeck. On opening night Marcelino Sambé danced him as if his own life depended on it. He had even developed a special hunched walk, a depressed and self-protective hobble, that spoke volumes even when his back was turned to us. It was moving beyond words.

It's also worth noting that MacMillan, who himself suffered from depression and bouts of crippling insecurity, made this ballet in 1984, at a time when the words "mental" and "health" rarely appeared in the same sentence, and in the face of widespread opposition to work such as this on the Covent Garden stage. He was accused of being on a mission to "destroy ballet", and ballet fans felt obliged to decide whether they were for or against him. One only wishes he could have lived long enough to overhear the comments of punters exiting towards the bars in the second interval the other night. Young people in particular are bowled over by the work's conviction and dramatic power.  The final work of the evening has been less neglected, its sublimity making it an easy choice to close almost any Royal Ballet mixed bill. Who doesn't love Fauré's Requiem, with its extraordinary "Pie Jesu" floating high above the treble stave like a layer of cirrus clouds. Here, MacMillan gives us an image of white-clad women carried horizontally, like travelling angels. (Pictured above, Lauren Cuthbertson and Matthew Ball)

The final work of the evening has been less neglected, its sublimity making it an easy choice to close almost any Royal Ballet mixed bill. Who doesn't love Fauré's Requiem, with its extraordinary "Pie Jesu" floating high above the treble stave like a layer of cirrus clouds. Here, MacMillan gives us an image of white-clad women carried horizontally, like travelling angels. (Pictured above, Lauren Cuthbertson and Matthew Ball)

As with the previous piece on this programme, the work's creative thrust is the product of difficult personal experience. In 1976 MacMillan was processing the shock and grief of losing a close friend, the choreographer John Cranko, and the startling opening image – a phalanx of dancers shaking their fists at the heavens – surely springs from his rage and bewilderment. As the ballet progresses the mood turns to serenity and acceptance, working both through and against the Latin words of the Catholic mass for the dead – because MacMillan wasn't in fact religious. Remarkably, Requiem rises above such petty distinctions by being ecumenical, monumental and timeless. By the final number, "In Paradisum", as the entire cast step one by one into a space of pearlescent light, applause feels inappropriate and intrusive.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Vollmond, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch + Terrain Boris Charmatz, Sadler's Wells review - clunkily-named company shows its lighter side

A new generation of dancers brings zest, humour and playfulness to late Bausch

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Phaedra + Minotaur, Royal Ballet and Opera, Linbury Theatre review - a double dose of Greek myth

Opera and dance companies share a theme in this terse but affecting double bill

Add comment