“The street I grew up in had no name and is in a country that no longer exists,” director Milisuthando Bongela begins her meditation about growing up in Transkei, a semi-fictional black nation which helped facilitate apartheid yet felt like a utopia.

Bongela splices forgotten archives of polished propaganda, raw videotaped reality and painful conversation to understand her own racial reality, and how colonial scars can be complimentary yet invisible for black and white South Africans today. White hands are shown etching borders and conjuring flags, stamps and anthems as Bantustan “homelands” such as Transkei were written into being in 1976 by PM John Vorster, who explains apartheid’s “separate flowers” racial theory with folksy warmth. Milisuthando acts as a ritual exorcism of this past, first returning to the director’s nonagenarian grandmother’s home in a sparse village clinging to bare terrain under big, gloomy skies. Bongela reconnects with her birthplace through rural chores and social communion, sinking back into landscape, language and ancestral roots. This quietly observational passage also recalls her childhood’s potent female role models with their “high heels and perfume”, and her parents composing music and dancing, getting on with full lives seemingly liberated from absent whites, while, Bongela now realises, “living inside the dream of apartheid”.

Milisuthando acts as a ritual exorcism of this past, first returning to the director’s nonagenarian grandmother’s home in a sparse village clinging to bare terrain under big, gloomy skies. Bongela reconnects with her birthplace through rural chores and social communion, sinking back into landscape, language and ancestral roots. This quietly observational passage also recalls her childhood’s potent female role models with their “high heels and perfume”, and her parents composing music and dancing, getting on with full lives seemingly liberated from absent whites, while, Bongela now realises, “living inside the dream of apartheid”.

The averagely happy black place she was born into in 1985 doesn’t fit the official, simplified history. From Transkei’s swiftly erased 18-year reality to her middle-class media worker’s life and white neighbours in Johannesburg now, where is she in this racial web?

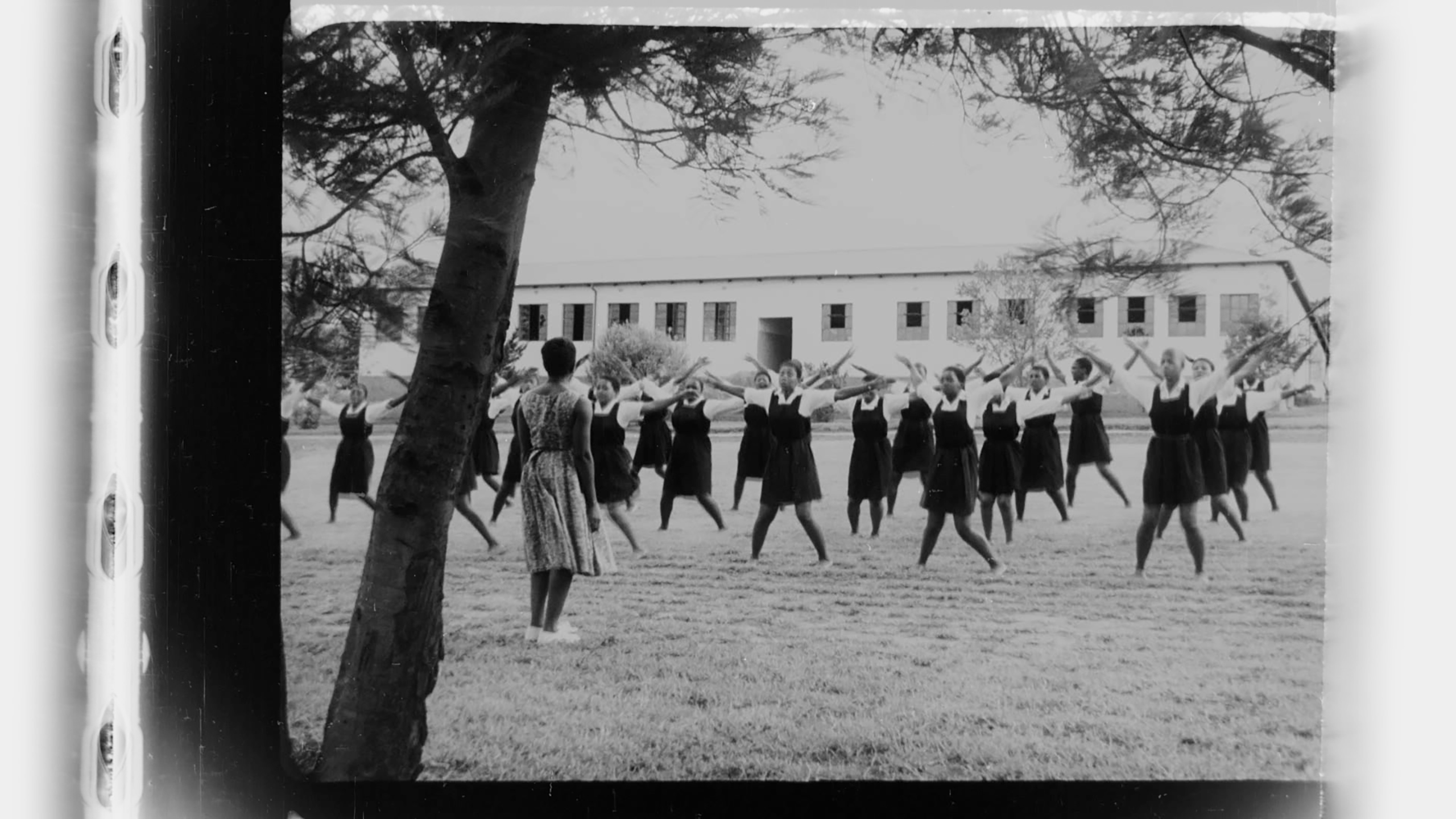

Bongela doesn’t rehash the bloodied black flight from batons, dogs and guns which made South Africa an international pariah. She’s interested instead in softly persuasive domestic footage, the separate fantasies of the distant white regime and insular black homelands they reveal, and the pain they numbed and concealed for a while. Rousing reports of “independence” ceremonies, militaristic formations of health and efficiency female gymnasts and marching majorettes, topless Bantu women and Afrikaners in Boer national dress are intercut to an orchestral crescendo, the militant rosiness and athletic rigour recalling Aryan purity. Folk tales, parables and dislocating rituals try to discern a deeper path. Bongela’s childhood excitement at a 1992 move to East London with its suddenly available beach and restaurant is then only slightly spoiled by their house being egged, just as black kids' pioneer innocence on entering white schools ignores white adult screams of hate - awkward static in Mandela’s charismatic new vision when, Bongela remembers, “the promise of belonging hung like a rainbow after a storm”.

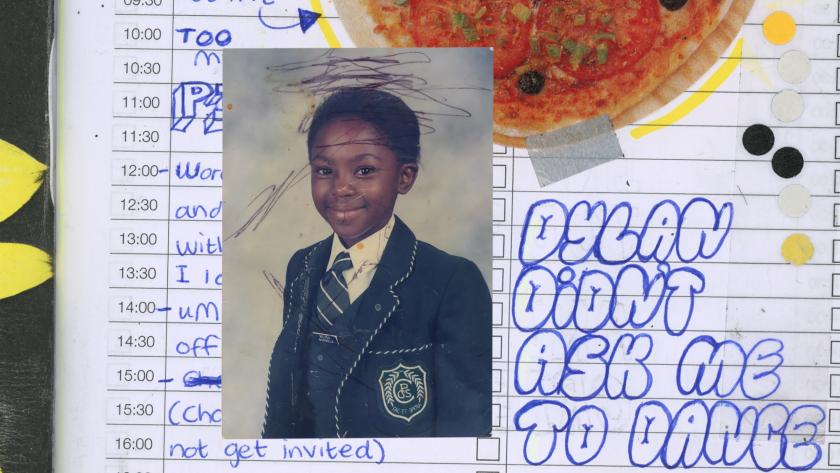

Folk tales, parables and dislocating rituals try to discern a deeper path. Bongela’s childhood excitement at a 1992 move to East London with its suddenly available beach and restaurant is then only slightly spoiled by their house being egged, just as black kids' pioneer innocence on entering white schools ignores white adult screams of hate - awkward static in Mandela’s charismatic new vision when, Bongela remembers, “the promise of belonging hung like a rainbow after a storm”.

Bongela’s white friends make agonised family confessions on audio-only, black screens. A more positive inheritance is found when grandmother Somikazi Victoria Ntikinca is buried aged 93. A photo of her vibrant youth and her elderly wisdom sum up a woman who outlived apartheid and ephemeral Transkei. “Pray for all that’s happened that can never change,” Bongela asks. This poetic film elegantly divines forgotten tributaries of what happened to South Africans, and connects to salving, ancient truths.

Add comment