Valiant souls who have recently read the Margaret Atwood trilogy on which this new Wayne McGregor piece for the Royal Ballet is based will be at home with its time-shifting eco-sci-fi narrative. The rest of us, not so much.

The appeal of the basic plot is clear: how big pharma coped with a devastating pandemic that has wreaked havoc on an increasingly plundered Earth. (NB the novels appeared between 2003 and 2013, long before the pandemic; and McGregor’s first planning, collaborating with the National Ballet of Canada, to create a piece on them, began in 2017.)

Restocking the world with new “people” is the life’s work of mastermind Crake, who decides to wipe out the plague’s straggling survivors and start again. We join this dystopian story in the early days of his new breed, the Crakers, who are peaceable vegetarian humanids with eerie singing voices, which the score echoes here and there. Love is in the air again. Not least for Crake’s old friend Jimmy, who is one of the few 100% humans to survive the plague and is still consumed with passion for Crake’s partner, Oryx. We follow the Crakers far into the future.

To project this epic storyline, McGregor and his regular team employ variants of techniques they used in their beautiful 2015 piece, Woolf Works. A narrator greets us, as a recording of Virginia Woolf did, but here it’s a child with a synthesised voice explaining in a singsong some of the awful things that happened on Earth during the Chaos and Crake's “Waterless Flood”, in which people killed each other and ate Oryx’s “children” – the natural world. To create this otherworldly but oddly abstract place, the set is hung with a series of projections, some on a full-size scrim, some on an egg-shaped structure in the middle of the stage, visuals that are always on the move.

To project this epic storyline, McGregor and his regular team employ variants of techniques they used in their beautiful 2015 piece, Woolf Works. A narrator greets us, as a recording of Virginia Woolf did, but here it’s a child with a synthesised voice explaining in a singsong some of the awful things that happened on Earth during the Chaos and Crake's “Waterless Flood”, in which people killed each other and ate Oryx’s “children” – the natural world. To create this otherworldly but oddly abstract place, the set is hung with a series of projections, some on a full-size scrim, some on an egg-shaped structure in the middle of the stage, visuals that are always on the move.

McGregor is reunited here with Max Richter, the composer with whom he worked on Infra and Woolf Works. Richter serves up his usual fare: solemn arpeggios with a repeated melodic line on top, and sometimes a walking bass underneath. For variety, this style comes with different lead instruments – a cello, a guitar, a harp – and also choral passages, hymn-singing and added effects such as whispering and industrial noises. His technique is the same in each act: a gradual swelling of the sound, layered into a magisterial crescendo, then a dying down.

In deference to the book’s complex time patterning, McGregor has positioned the Extinctathon, a computer game the young Crake mastered with his friend Jimmy, as Act Two, following the events that the game helped generate that are depicted in Act 1, though both acts end with the same scenario, of survivors struggling in a fog. In Act Three we move forward several generations to the world Crake’s bioengineering has created, which choreographically is reminiscent of the sea creatures in the last act of Woolf Works, with groupings of the Crakers in fluctuating patterns and combinations.

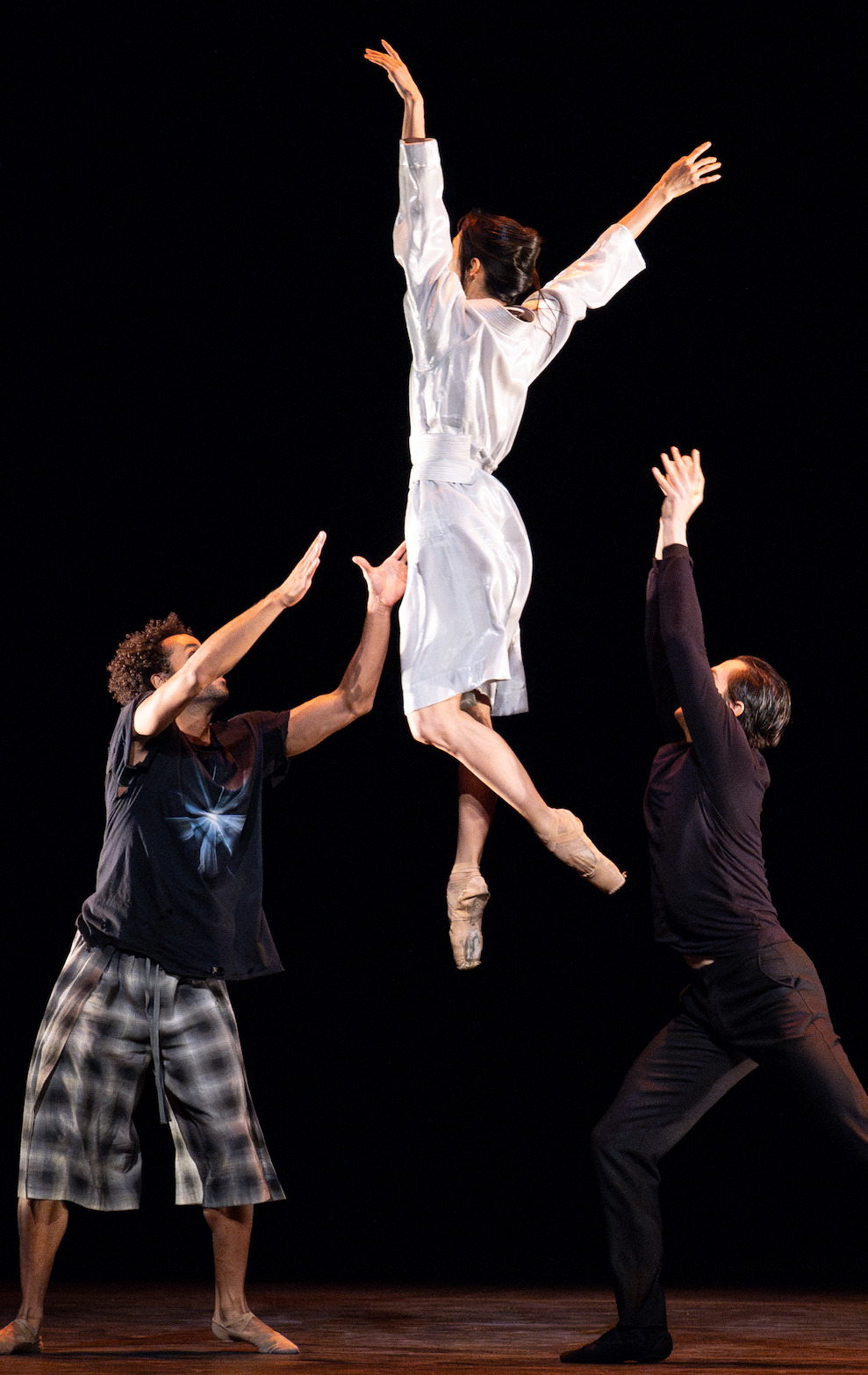

This arrangement allows the three leads – on opening night, principals William Bracewell as Crake (pictured above with, from left, Joseph Sissens and Fumi Kaneko) with Joseph Sissens as Jimmy and Fumi Kaneko as his earth-motheresque wife Oryx – to be introduced in Act One centerstage and given seductive pas de deux and a key pas de trois in which they wind limbs around each other in sinuous embraces. Their love for each other is clear.

The three dancers clearly relish the challenges of McGregor’s signature style, as do Melissa Hamilton as Toby, one of the hippie-ish God’s Gardeners faction we meet in Act Two, and Lukas Braendsrod as Zeb, her beloved. All McGregor’s usual moves are here: wild extensions and swooping lifts, sensuously undulating bodies and improbably fast chainés, every gesture worked up to perfection. As dancing, it’s stunning. The excellence of the cast, though, has to compete with the efforts of the rest of the artistic team, especially the set design, which is constantly changing and becomes a distraction. The eye darts hither and thither but rarely focuses on one compelling element of the stage picture or the miraculous balletic feats of the dancers. The relative calm of Act Three is a relief, though the Crakers, whom we see fashioning effigies of their heroes, Toby and Jimmy, almost outstay their welcome. They are joined by the bulbous horned creatures of Act Two (pictured above) once hunted by Toby but now the Crakers’ unhunted friends, as well as by Crake, Oryx, Toby and Zeb in flesh-coloured leotards that make them seem almost naked. (Why, in plot terms, are they there – as spirits? Dramatically, though, it feels right.)

The excellence of the cast, though, has to compete with the efforts of the rest of the artistic team, especially the set design, which is constantly changing and becomes a distraction. The eye darts hither and thither but rarely focuses on one compelling element of the stage picture or the miraculous balletic feats of the dancers. The relative calm of Act Three is a relief, though the Crakers, whom we see fashioning effigies of their heroes, Toby and Jimmy, almost outstay their welcome. They are joined by the bulbous horned creatures of Act Two (pictured above) once hunted by Toby but now the Crakers’ unhunted friends, as well as by Crake, Oryx, Toby and Zeb in flesh-coloured leotards that make them seem almost naked. (Why, in plot terms, are they there – as spirits? Dramatically, though, it feels right.)

But I cannot lie: not having read the Atwood novels, I would be lost without the synopsis in the programme and the contents of its essays. Should audiences have to work so hard? McGregor is proud of his lengthy collegiate approach, kicking ideas around within his team, but you suspect they became so steeped in their preparations for Maddaddam that it lost the singular vision and clear focus it needs.

Add comment