La bella dormente nel bosco/L'enfant et les sortilèges, Royal College of Music review - pure theatrical magic | reviews, news & interviews

La bella dormente nel bosco/L'enfant et les sortilèges, Royal College of Music review - pure theatrical magic

La bella dormente nel bosco/L'enfant et les sortilèges, Royal College of Music review - pure theatrical magic

Fairytale operas by Respighi and Ravel come together to create enchantment and danger

Childhood fantasies and adult fears – sometimes it’s a fine line between the two. And it’s one that director Liam Steel walks with unerring precision in his ravishing new double-bill for the Royal College of Music: an overflowing toybox of invention and imagination that conceals, right at the bottom, something rather nasty and very real indeed.

The production brings together Ravel’s familiar L'enfant et les sortilèges – Colette’s compact fable of a naughty boy who is taught a fantastical lesson in humanity – with a rarity, Respighi’s La bella dormente nel bosco. Premiered in 1922 and reworked extensively, this Sleeping Beauty retelling started life as a marionette opera, and even in its later forms retains something of that strange, magical artifice.  Rather than fight tension that’s wired into glistening score sewn together with the silver threads of harps and high woodwind, Steel and designer Michael Pavelka lean into it with a staging that puts puppets front and centre – illusions all the more enchanting for being performed in plain sight.

Rather than fight tension that’s wired into glistening score sewn together with the silver threads of harps and high woodwind, Steel and designer Michael Pavelka lean into it with a staging that puts puppets front and centre – illusions all the more enchanting for being performed in plain sight.

A framing prologue introduces us to a small boy, whose tatty copy of Sleeping Beauty lies beside him on the floor. But his playtime is interrupted; his mother sweeps his toys aside, leading him away with a man who stands silently in the background. More of them later.

Meantime, we’re suddenly inside the story itself. Everything here is alive, whether it’s a cat, curling up under a tail flicked by his own puppeteer, trees that bend and assemble on command, or some ingenious frogs – a perfect illusion. The courtiers are wearable puppets – human from the waist down, wooden from the waist up, manipulated by the singers themselves. It’s like Brecht, fairytale-style. Best of all are the fairies – suspended, glowing and darting, in mid-air by little more than some clear plastic binbags and fairy-lights.

Meantime, we’re suddenly inside the story itself. Everything here is alive, whether it’s a cat, curling up under a tail flicked by his own puppeteer, trees that bend and assemble on command, or some ingenious frogs – a perfect illusion. The courtiers are wearable puppets – human from the waist down, wooden from the waist up, manipulated by the singers themselves. It’s like Brecht, fairytale-style. Best of all are the fairies – suspended, glowing and darting, in mid-air by little more than some clear plastic binbags and fairy-lights.

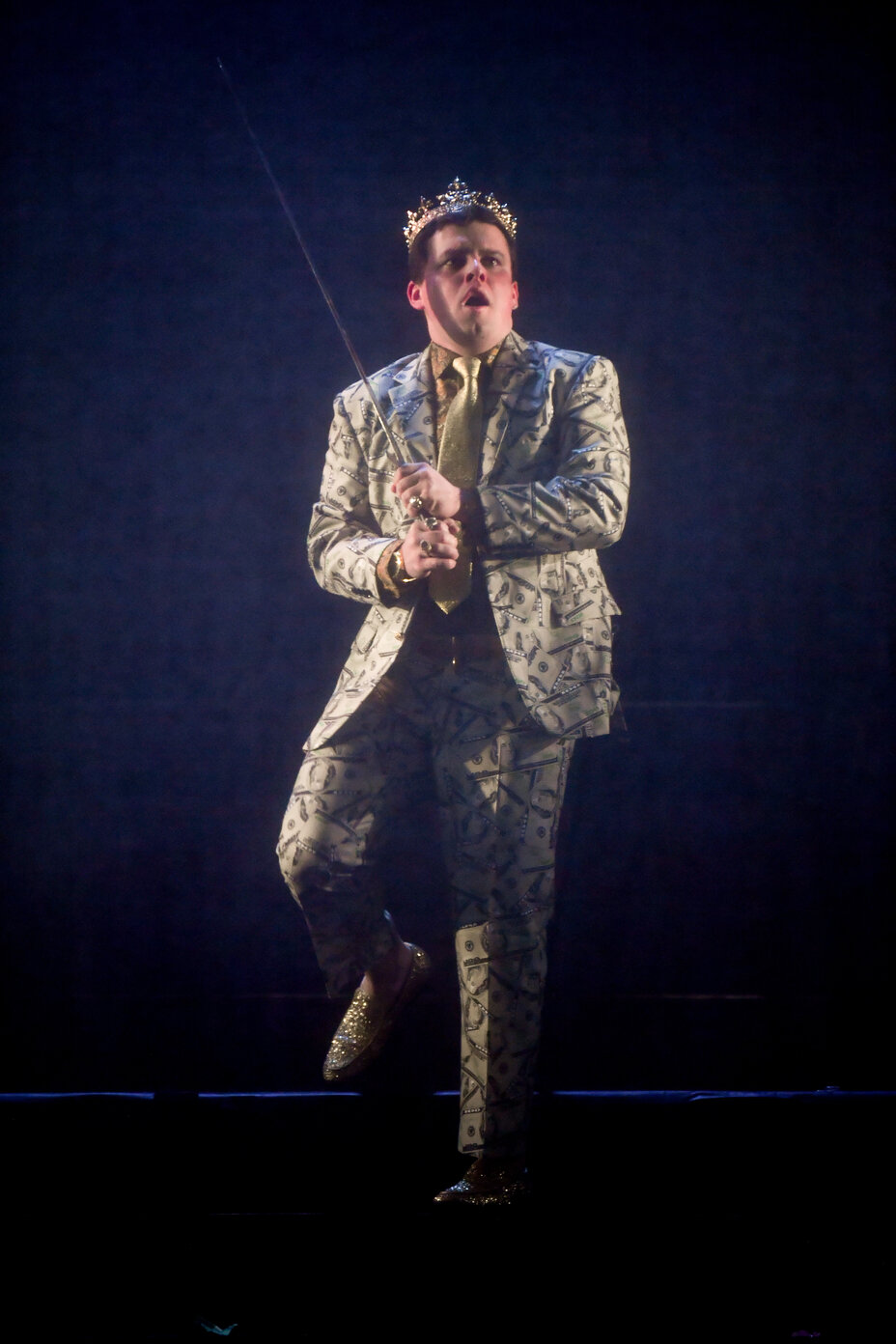

Respighi’s score has never met a composer it didn’t like. There’s a lot of Massenet here (the Blue Fairy’s silvery coloratura owns the debt openly), some Debussy, Stravinsky, even a swerve into Wagner in a climactic love-duet for The Princess (Lylis O’Hara) and Prince April (Dafydd Jones pictured above). But, as patchworks go, it’s a charming one, full of the all the orchestral colour you’d expect – as well as some you wouldn’t.

Conductor Michael Rosewell helps draw out all these inflections from his student orchestra, while a strong cast (one of two) throw themselves at all of Steel’s challenges with gusto. Seonwoo Lee’s Blue Fairy dispatches immaculate volleys of sweetness – an other-worldly foil to O’Hara’s full-blooded Princess (no pastels here). But the stand-out is young Welsh tenor Dafydd Jones – gleaming bright of tone, and gloriously even right through the range – whose Prince is ready to step out onto a major stage tomorrow. I predict big things.  It's all thoroughly delightful, and if the evening ended there it would be very good indeed. But it’s in the second half that this show becomes something else. Steel doesn’t so much weave the operas together, as expose connections that were already there. The princess that Ravel’s small boy called out to in his dreams the night before, becomes Respighi’s; the small boy of the start of the evening is revealed as Ravel’s L’enfant, his lashing-out here less tantrum-rage than damaged, self-destructive sadness.

It's all thoroughly delightful, and if the evening ended there it would be very good indeed. But it’s in the second half that this show becomes something else. Steel doesn’t so much weave the operas together, as expose connections that were already there. The princess that Ravel’s small boy called out to in his dreams the night before, becomes Respighi’s; the small boy of the start of the evening is revealed as Ravel’s L’enfant, his lashing-out here less tantrum-rage than damaged, self-destructive sadness.

The opera’s echoes of WWI are picked up in a 1950s setting. The boy’s mother (a war widow?) is wrapped up in her new man, who threatens the child with his belt. This violence sets the afternoon of destruction in motion, innocent outbursts transformed into echoes and symptoms of abuse. When the two cats croon their raunchy duet, they are briefly replaced by the mother and her lover – a projection of the child’s feverish fears.  Steel doesn’t forget to bring the delight too. The playful set never ceases giving up its secrets. Mr Arithmetic appears from inside a schoolroom desk; The Armchair is a scarecrow made from stuffing; The Teapot becomes a Mexican wrestler, complete with kettle-mask; the shepherd’s dead sheep combine bloody throats and nifty choreography. It’s all giddily resourceful. Lexie Moon balance sullenness and warmth in a carefully pitched, understated performance as L’enfant, Sofia Kirwan-Baez (pictured in penultimate image) gives us plenty of vocal glitz as Fire and Daniel Barrett relishes the manic comedy of the Grandfather Clock.

Steel doesn’t forget to bring the delight too. The playful set never ceases giving up its secrets. Mr Arithmetic appears from inside a schoolroom desk; The Armchair is a scarecrow made from stuffing; The Teapot becomes a Mexican wrestler, complete with kettle-mask; the shepherd’s dead sheep combine bloody throats and nifty choreography. It’s all giddily resourceful. Lexie Moon balance sullenness and warmth in a carefully pitched, understated performance as L’enfant, Sofia Kirwan-Baez (pictured in penultimate image) gives us plenty of vocal glitz as Fire and Daniel Barrett relishes the manic comedy of the Grandfather Clock.

But the test of any L’enfant is the ending. Does that final cry of “Maman!” get you where it hurts? Absolutely. Steel finds the spot and then presses harder. Fears and fantasies, pleasure and pain: it’s all one in this gloriously topsy-turvy psychoanalytic dreamworld.

- The double-bill is at the Royal College of Music's Britten Theatre until 18 March

- More opera reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Add comment