One wearies of quarrelling with opera directors’ concepts. But what’s the alternative? To ignore or acquiesce in crude, approximate reimaginings that, like Daisy Evans's new La Traviata at Longborough, stuff a work any old how into some snappy, after-dinner parody that says nothing useful about the piece, vulgarises the situations and confuses or misrepresents the text.

Evans’s Violetta is the star of a film about Marie Antoinette. Marie who? Not Duplessis, evidently, Dumas’s own lady of the camellias. A hint at the eighteenth-century costuming of the original 1853 production? Hardly: that was “circa 1700.” Perhaps they’ll guillotine Violetta in the end. No such luck. She dies here, like all miserable film stars, from a drug overdose, with the poor French queen long abandoned.

But wait: what about Alfredo’s poor sister back in Provence? Where? Surely we’re in Hollywood. Well, it’s true non-Italophone audience-members won’t get that detail, evaded by the surtitles, but it’s still there in the sung text. You see, the sister’s fiancé is refusing to marry her because of her brother’s irregular life-style. Oh, come on, pull the other leg! In modern Hollywood? No, in 1850s Provence. Are you saying Alfredo’s dad has come all the way from Provence to rescue Alfredo from the #MeToo brigade? Why not send an email? Don’t be silly, that would ruin Act 2.

So, does the film get made? No, it seems to get forgotten, except that it’s not quite clear whether all the shenanigans about Alfredo’s sister and Flora’s party is part of a film or part of life. There are still spotlights and a film crew all over the place in Loren Elstein’s sets, and Violetta’s country house looks like a Potemkin beach hut, with a front and no back. OK, but at least you get that wonderful music. Yes, well, nearly all of it. Evans seems not to like the last few bars, so she trims them a touch, and when Violetta sings the bit about feeling better then drops dead, the others are so upset that they forget to sing their own lines. Not that it matters, since the director has cleverly placed the death scene downstage next to the proscenium arch where a lot of the stalls audience have to crane see it.

So, does the film get made? No, it seems to get forgotten, except that it’s not quite clear whether all the shenanigans about Alfredo’s sister and Flora’s party is part of a film or part of life. There are still spotlights and a film crew all over the place in Loren Elstein’s sets, and Violetta’s country house looks like a Potemkin beach hut, with a front and no back. OK, but at least you get that wonderful music. Yes, well, nearly all of it. Evans seems not to like the last few bars, so she trims them a touch, and when Violetta sings the bit about feeling better then drops dead, the others are so upset that they forget to sing their own lines. Not that it matters, since the director has cleverly placed the death scene downstage next to the proscenium arch where a lot of the stalls audience have to crane see it.

But there must have been compensations. Yes: one big one for a start. Claire Egan, a young New Zealand soprano out of the Cardiff Academy of Voice, is a talented singer we’ll be hearing a good deal more of (though here acting as cover for Anna Patalong, who sings most of the run). Egan has vocal brilliance and a strong stage presence and knows how to move. Not only was her first act aria done with real style and mature control (despite Daisy Evans having her distractingly, and very uncanonically, screwed by Alfredo on the film set during verse two of “Sempre libera”), but she held the empty stage alone in a beautiful account of “Addio del passato” at the start of Act 3.

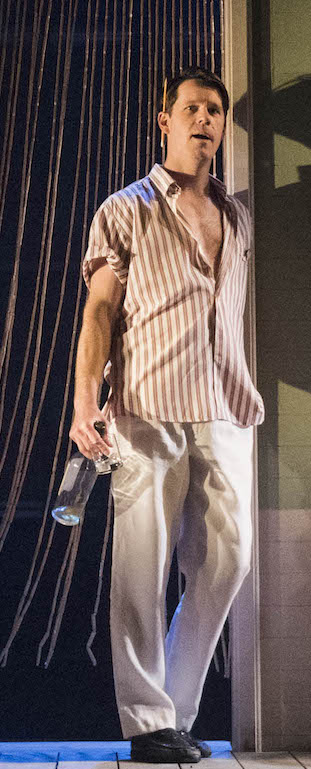

She was also the only lead singer on this first night who handled the small Longborough house with some sense of its intimacy. Peter Gijsbertsen (pictured above) tended to oversing early on and had momentary troubles in Act 2: a nice singer with a shade too much of the I-am-an-Italian-tenor. Good, though, in the emotionally violent third act, which also showed what Evans can do when she forgets concept and concentrates on the musical dramaturgy. The ensemble singing and dancing in this scene were excellent, with two or three lively cameo performances (Samantha Price as Flora, Aled Hall, who had, and gave us, fun with his camped up Gaston, Eddie Wade as a sturdy, bespectacled Douphol).

The weak link vocally is Mark Stone’s Germont père, too big for the house and often giving the impression of being barked out over the orchestra, too much volume, not enough lyrical line and even, at times, very questionable intonation. His great scene with Violetta isn’t helped by the cramped, flat-front staging, but needs above all a more tender approach to Verdi’s wonderfully sensitive word-setting. La Traviata was not just new in its contemporary setting; it was radically new in the intimacy and precision of its psychology. It’s an opportunity, but also a challenge.

Thomas Blunt conducts, tactfully if not always tidily. He could rope in some of the indiscipline in the singing. Alas there’s not much he can do about the concept.

Add comment