theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Directors Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Directors Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser

theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Directors Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser

Opera's Gilbert and George on their unique 30-year collaboration as directors

It is rare enough for directors to collaborate in theatre, even rarer in opera. Patrice Caurier (b. Paris, 1954) and Moshe Leiser (b. Antwerp, 1956) began their long collaboration in their 20s. They are now in their 50s, and since that first production of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Opéra de Lyon in 1982, they have never worked (or lived) apart. Cohabiting and collaborating, they are opera’s closest equivalent to Gilbert and George.

As personalities they could not be more different from each other. Caurier is careful and reserved, Leiser fiery and voluble. While their work increasingly takes them across the world, the majority of it has been in France and Switzerland. While they staged La belle Hélène for Scottish Opera, their principal relationship in this country was with Welsh National Opera until they began to work regularly at the Royal Opera House. In Covent Garden they have staged Hamlet, Madama Butterfly and Hänsel und Gretel, but they are overwhelmingly identified with their triptych of Rossini operas: Il turco in Italia, Cenerentola and Il barbiere di Siviglia.

Turco returns with young Polish soprano Aleksandra Kurzak as Fiorilla (pictured below © The Royal Opera/Clive Barda), joining Ildebrando D’Arcangelo as Selim the Turk and Alessandro Corbelli as Don Geronio, both survivors from the joyous original production in 2005. Caurier and Leiser talk to theartsdesk about their unique directorial double act.

JASPER REES: You are celebrating your 30th professional anniversary in two years. How will you mark it?

JASPER REES: You are celebrating your 30th professional anniversary in two years. How will you mark it?

PATRICE CAURIER: I hope doing a nice production with people you love. I don’t know what it will be. Honestly I forgot. The only thing would be to meet with some people that we really care for that we have met in all those years.

Which production will you be directing?

MOSHE LEISER: I swear to God we haven’t thought about that. We are not counting, we are too busy.

PC: We try to keep gaps because to go from one thing to the next is just too tiring and we are not strong enough.

What is a good gap?

ML: A minimum of three months. You need one month to unwind, one month to really enjoy your holiday and then one month to get back in gear and charge your batteries and your energy for the next one, but it doesn’t happen often.

PC: We have three months without rehearsals but it’s never three months without work.

How long did you have before this?

ML: Just the time to jump on the plane on opening night at the Met and get here the next morning. So that was zero time.

PC: Like that you’re not bothered with the jetlag.

But if there are two of you does that not halve the burden?

PC: It sure helps because you know we can share the difficulties. But you still have to do the work. But it helps because we can exchange, we can speak about it and you don't go back alone to your hotel or your apartment.

Is there less work doing a revival?

PC: In advance, yes.

ML: But you know, people say, "Oh it’s a comedy, it’s wonderful, it’s light, it’s less work." That’s bullshit. A comedy is always more work, because things have to be precise. Things happen fast and there is a lot of articulation and if you want to match Rossini’s virtuosity you have to be as bright and sharp as he is. And that requires from the director to push the singers to go into that mode and not go into the easy mode.

You need coloratura directing?

ML: You need timing, you need them to understand that you don’t play funny, you play the situation, that the only people who knows it’s a comedy is the audience, not the characters - all the things that do not come as granted in the beginning. And it takes time, it takes a lot of energy. The amount of work that you need to have all the timing right and the "madness", between quotation marks, of Turco in Italia, for that madness to develop and people to follow a story, if you play the situation with the humour and the music then there is a chance that people will laugh and enjoy it. In other words the problem with comedy is to keep the horizontality of the story and not to stop with the verticality of the gag. It takes a lot of energy.

I am shock and awe. Patrice is reconstruction

One thing that was very apparent in the first version of this production was that Cecilia Bartoli is a brilliant comic actress. Did you know how brilliant she would be?

ML: No, it was the first time we worked with her.

PC: Someone who is so intelligent in her interpretation, who has so many colours when she sings, such an invention and imagination, gives you an idea that she has something to say. As Moshe said, it was the first time we met her, so you don’t know how she will be, how she will react, but you know you have to deal with someone of already very very high level. And that helps.

ML: Cecilia is really a world star. When you don't know her of course you are always a little bit nervous because you don’t know what the working relation will be. You admire her not for being a star; you admire her because she is s queen of interpretation. There is never an empty note in what she does. That’s why we were so excited to work with her. And the great surprise was that she is the most simple, adorable, open, dedicated, collegial person. And that was a joy. Generous is always a word I would use to characterise her, because in the work there is never, “I preserve myself”. It is always “I give, I give, I give, I give”. It’s a very open process.

PC: Just to tell you one thing. At the end of the opera there is a very long aria. We cut probably half of it or a third of it and it was on Cecilia’s request. We haven’t cut it because we thought, we are doing it with Cecilia. And she said, “No, it's not a good idea. It’s too long. It was done for a singer to show off. It should remain in proportion, it’s an ensemble piece. It’s Turco in Italia, not Fiorilla. So it has to remain in proportion.” I thought that was so right and it just shows the kind of person she is.

She argues that the opera is about female emancipation. Do you agree?

ML: Well, I don’t agree with that as a final description of what the opera is about. It’s also about that but for me it is more about desire and in that case, yes, the right of a married woman to have desire when she’s not totally happy with the one she’s probably not getting much from. So there is that. It is already very incredible to put as a positive character someone who wants to be adulterous. It’s amazing. I mean the 19th-century bourgeoisie would have never admitted a libretto like that.

Does that explain its lack of initial success?

PC: I have no idea. Until now it’s an opera that doesn’t have such a high reputation as the three others, the most well known of Rossini. I don’t know why. I find that it works beautifully.

ML: There is less storytelling in Turco in Italia than in Cenerentola or Barbiere. Barbiere is really a play. You feel that it is a play. Cenerentola you feel that it is a fairytale that he wants to tell. Turco in Italia is much more modern and contemporary. The structure is loose. The Pirandello aspect of the theatre is very surprising for a libretto at this time. That opens an incredible world of freedom in how you tell that story. There is much more freedom in Turco in Italia than in Barbiere and Cenerentola.

You have also staged Madama Butterfly and Hänsel und Gretel (pictured left: Angelika Kirchschlager as Hänsel and Diana Damrau as Gretel © Bill Cooper) at the Royal Opera House. But three Rossinis suggests a special affinity. Could you explain what it is about the composer that you are particularly attracted to?

You have also staged Madama Butterfly and Hänsel und Gretel (pictured left: Angelika Kirchschlager as Hänsel and Diana Damrau as Gretel © Bill Cooper) at the Royal Opera House. But three Rossinis suggests a special affinity. Could you explain what it is about the composer that you are particularly attracted to?

ML: It is a big question.

PC: First of all, we discovered him through doing his operas. Of course we know these pieces but it’s not until you really work on them that you know what a musician and what a theatre man he is. We’ve just done in Zurich Mosè in Egitto, which was our first Rossini opera seria. We discovered it again. It’s not a good libretto, really not, but how he succeeds despite of that to make theatre all the time – it is a genius composer.

ML: Rossini is a language. He offers always very strong structure. The form is absolutely clear and it’s an open form, which is that when you come to direct it, you are not dealing with psychological theatre or romantic theatre, where the music tells you exactly what everyone feels. You can in Rossini use the same music for a comedy and for a tragedy. If you take moments of Mosè in Egitto you’d think it’s music of a comedy. Or if you take some music in Turco in Italia it could work very well for an opera seria. I’m talking about the Fiorilla aria, for instance. The genius of Rossini is that he is open. He proposes a very logical structure that is always right as far as timing. But as it is not psychological it has an incredible appeal for theatre. You find in Rossini an accomplice. He says, “This is what I propose. Now make something out of that.” It’s open. And that’s what I love in Rossini. There is really madness in his writing. There is really pleasure. There is a really a joy and very clear understanding of human behaviour. And I think that’s what makes him priceless. It’s not the melodies; it’s not even the fast music. It’s not the coloratura. It’s the incredible intelligence he has in analysing a situation.

Patrice, you are doing less of the talking. Is that how it happens in the rehearsal room as well?

PC: Oui.

Could you put your finger on why that is the case?

PC: Because we are different. I think it s a question of personality. More than anything, and a different way to do things.

ML: I can explain for 10 minutes something to a singer and then Patrice will say two words and the singer will understand it much better.

PC: But it’s easier if the talk has been done before, because it gives me the time to summarise. It’s more difficult sometimes when you are in the fire of the action.

Also Moshe has battered down the singer’s defences.

ML: I am shock and awe. Patrice is reconstruction.

It is quite unusual for directors to work together even occasionally, but to manage it without a break for so long is a remarkable rarity anywhere in the arts. Why does this partnership work? Why does it thrive and survive?

ML: It’s not an easy relation, of course. Over the years things do change and you must find a way to keep the interest of that relation alive. There are moments of big frustration: I can be impossible and Patrice can be stubborn and we can disagree on things, mostly before we meet the singers. Not once they’re there. Once they’re there all the mines have been taken away and the field is free to walk on.

You present a united front to your cast?

ML: Yes, because we at least agree on the general direction of where we should go. We can disagree about this moment or that moment, and that will always be a source of conflict, and that is fine, I find. The important thing of the relation is to realise that from the first time you have an idea about the piece, it is already confronted through the scrutiny of another brain. That you are not alone with your genius work, creating your own child blah blah blah blah. It’s rational experience. "What is the most important thing in that opera? What are we going to base it on? What is it about? How far can we go with the music, against the music, around the music?" All these questions are discussed a long time in advance and there can and there were and there will be strong disagreements about that, but by the end of the day when we work with the set designer and we decide on a space most of the questions have been solved. It’s not that we compromise. We are not compromising and the discussion can be very violent. But at a certain time a decision will be taken. Then we are both clever enough to leave behind our narcissistic pretensions and let the piece breathe by itself. Why does that relation work for 30 years? Because it works.

Very few directors have a genuine interest in the art form. Most of the time they’re charlatansPatrice, do you agree?

PC: Yeah, yeah, I do. And also something very strongly we have in common is that opera is teamwork. You are never alone. Never. You are always confronted with the work of other people. So from the start it’s something where you have to deal with others. We have the same team also, the same set, costume and light designer for years. And also with a conductor. If you don't agree, if you don’t work together, one foot will always be missing. I imagine it’s much more difficult to paint with four hands than to stage with two brains or two mouths.

Have there been occasions when one has been more eager to work on a particular opera than the other?

PC: Oui, oui. We are different. I think I would say that I love opera more than Moshe does, as a form.

ML: I never listen to opera. You’ve got two types of opera that I hate. One is the opera where it’s all about the singing and the beautiful images and I just can’t stand that. It’s for me worse than prostitution. Why spend the money? Why bother? For the rich people who can afford the ticket and to come to listen to wonderful words, wonderful costume, wonderful images? Not interested. Thank you very much, give the money to the hospital. The other thing about opera that I really hate is what you call fashionable opera where someone who has no connection at all to doing work with a singer will come and do an opera because you’ve got the name. A filmmaker, a choreographer, a fashion designer. To stage an opera you need an incredible amount of expertise, theatrically and musically. It is a job. If you want to do it not superficially. And I cannot take the entertaining side of name-dropping and excitement about nothing.

I think that opera, like all performing arts, are places where we reflect on what we are and for that singers are not carriers of beauty. They should be witnesses of human behaviour. And that has to be true, whatever the theatrical form it takes. The relation between the words, the music and the situation is the core of opera. If that is not worked on in depth, it’s bullshit. Close this place. Not interested. And it’s very hard to go there, because most of the time we are confronted with that. But very few of the directors that work in the opera world have a genuine interest in the art form and are going to convey something about human truth through theatre and music. That’s seldom. Most of the time they’re charlatans, that’s all I’ve got to say. And maybe successful ones. And I’m talking conductors as well. People with very big names who do sound instead of doing music. Or theatre directors that do images instead of producing truth onstage between characters so that it can reflect on something that is deep inside, whether it is a comedy like Turco in Italia or Butterfly or Hamlet or Götterdämmergung. That’s not the point. It’s always to try to find a form so that you can touch the core of what that piece is about.

I think that opera, like all performing arts, are places where we reflect on what we are and for that singers are not carriers of beauty. They should be witnesses of human behaviour. And that has to be true, whatever the theatrical form it takes. The relation between the words, the music and the situation is the core of opera. If that is not worked on in depth, it’s bullshit. Close this place. Not interested. And it’s very hard to go there, because most of the time we are confronted with that. But very few of the directors that work in the opera world have a genuine interest in the art form and are going to convey something about human truth through theatre and music. That’s seldom. Most of the time they’re charlatans, that’s all I’ve got to say. And maybe successful ones. And I’m talking conductors as well. People with very big names who do sound instead of doing music. Or theatre directors that do images instead of producing truth onstage between characters so that it can reflect on something that is deep inside, whether it is a comedy like Turco in Italia or Butterfly or Hamlet or Götterdämmergung. That’s not the point. It’s always to try to find a form so that you can touch the core of what that piece is about.

Who is the better musician of the two of the partnership (pictured above © Jillian Edelstein)?

ML: I think we are both musicians in that sense.

PC: We can read the score, work on the music. When we are round the piano with the singers or the conductor we are with the score and we can work with it. I mean I couldn’t conduct it, even though Moshe could probably. He often does.

ML: I hate it when singers come to the rehearsal with the CD libretto in their hand. I find that appalling. Absolutely appalling. When you are an opera director you are staging the music. Of course you are staging the relation between the words and the music, so if you just come with the words it’s pathetic. Directors that draw their logic from the words are as bad as conductors that draw their logic from the music. It’s in the interaction of both that the coherence lies.

Are there some places where these forthright attitudes ensure you are less likely to work? For example, La Scala?

PC: We’ve never worked in La Scala and I think it’s not a matter of where. It’s a matter of whom.

ML: I could work in the smallest house with a very big name. People think that the director is responsible for what you see and the conductor is responsible for what you hear. I think that’s bullshit too. It really is. It’s really the director that allows the music to exist and it’s the job of the conductor to make theatre in the pit. If you don't have that you don't have opera.

And that is why you don't see eye to eye with every conductor you work with?

PC: Of course.

Have there been times when you have wanted to work individually?

PC: No. We are satisfied. We didn’t feel the need.

ML: It has never happened.

Why did you feel the need do work together in the first place?

PC: We were young and we were both assistants and we talked a lot about the art form, what we wanted to do, and we had the same feelings about things.

How old were you?

PC: I was 28 and he was 26.

Did the opera house say yes to you because it was an insurance policy to give the job to two of you?

PC: Non, non.

ML: At the time in the Opéra de Lyon, it was still a period where you didn’t have to bring a media star to do your staging. You could in a house say, “Oh, here are two gifted assistant directors. Let’s give them an opportunity.” Actually it happened because normally it was the co-director of the house that was supposed to do the play, and he had to cancel for personal reasons. So suddenly they were looking and they said, “Why not ask them?” so that’s how it happened.

Here there are performers, singers and actors who are at such a level, and I wish the public would be at the same level

Did that confirm you in your desire to continue to collaborate?

ML: Obviously.

PC: We didn't even question it. It continued.

Were you already living together at that point?

PC: Yes, we were.

ML: It was at that moment that we met. We met in Opéra de Lyon.

You still live together. Is there a time when you can stop talking about work? Is there a curfew?

PC: No it’s never like that. We can stop but if we feel we want to talk about work. For example, when we are in production, the time when we are in rehearsal it’s only dedicated to the work, so when we go back home we continue to work. It’s just a habit. When we are in rehearsals we work all the time.

ML: It’s not the kind of job where you say, “Look, five o’clock, thank you very much.” You need obviously a moment to unwind, but according to what happens in the rehearsals, it can get us talking until three o’clock in the morning or we can come home and say, “Hey, it was a good rehearsal, let’s have dinner.”

PC: And we spend so much time with the score so it takes time. Comment dire? I think for that we have exactly the same idea. There is a responsibility when we do our kind of work. It costs a lot of money to the community or even to private foundations so I think if we are going to do it and spend that amount of money, you have to give all that you have.

ML: It’s tiring and it’s frustrating but it’s the only way to do it.

PC: There is an ethic. You have to devote all that you can to your work. It sounds like a big thing but we very strongly believe in it.

ML: Let’s face it, people are unemployed. We live in a crisis. There is so much misery. It’s indecent to put money in an opera house just for the sake of what a sort of bourgeoisie will call beauty. It’s a scandal. I’m shocked by it. I’m not shocked by it if people mastering their skill through the music, through the voice, try to find a way to touch the heart and the brain of an audience.

PC: Even if it’s a light comedy...

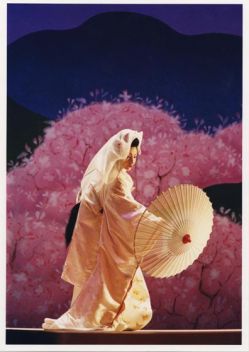

ML: That is priceless, because there are not many places in society where that happens. When you go to see a Broadway show or a West End show you know very well you are going to be entertained, you are going to get value for money, as they put it here. But that’s going to be it. That is the deal. I’m buying entertainment, I’m receiving entertainment, and the deal is nothing should remain. Nothing should upset you. When you go to a Shakespeare play or a Chekhov play or Götterdämmergung or Turco in Italia or Madame Butterfly (pictured left: Cristina Gallardo-Domâs as Cio-Cio San © Bill Cooper), the deal is not, “I’m paying a lot of money in order to be entertained.” The deal is, “I’m paying a lot of money because we’re dealing with some genius creation in mankind.” They are masterpieces, more or less, and we question masterpieces regularly to see if they still tell us something. If they don't tell us something what’s the point? And you cannot have an opera telling you something if it’s not carried by the soul of the singers. It’s just impossible. So your work is not to bring out beauty. Your work is to bring out truth. Your work is not to bring images. Your work is to bring special relations that make sense. Your work is not to impress with spectacular effects, but just to add the right set to allow what you have to say to be readable. It sounds theoretical but it’s not. It means that when you start an opera you don't have images in your head. You have an analysis in your head and you are going to go to the singers and try to find what’s happening there. "Why is it a piano? Why is it a forte? What’s the idea behind that? Why is that always sung on one note? Why are there silences in between the notes? What is the thought?"

I find that too many times the thought is abdicated in opera. I hate that. I think a good opera night is when you sit on the edge of your seat because something is happening in front of you that touches you, that appeals to you, that questions you, that upsets you, that makes you laugh, that makes you think. It’s a strong relation. For that to happen you must have something strong going on onstage. And it has nothing to do with beauty or entertainment. Like Shakespeare. Shakespeare is not entertainment. If he was only entertainment he would have been forgotten by now.

Do you have the same tastes musically? When you’re invited to do an opera by an opera house, are there times when one of you wants to do it more than the other? Or one of you is, for the sake of example, not a fan of Donizetti?

ML: That’s a common thing with both - not a fan of Donizetti.

PC: Sometimes it has happened that we have been offered to do a work, an opera that didn’t first really appeal to both of us. It will be a request from the head of the house.

ML: As opposed to something you are really interested in that you go to the opera house and say, “Can we do that?” That’s the opposite.

They tend to market us here with our “characteristic wit”. And you go, it’s not wit that characterises our work

Who would you avoid apart from Donizetti?

PC: Well, we are going to do one. I tell you, we are doing this Donizetti, for example, Maria Stuarda, but we do it for Joyce DiDonato and that is a good reason enough. We do it for her because sometimes there are some interpreters like here where it’s a good reason enough to do even a piece that you don't feel a strong relation with.

Who is that for?

ML: Houston, and the Liceu in Barcelona afterwards.

PC: As I listen to more music, I am very curious about opera. So I know there are some works that I am interested to do, especially works that I have never seen and are not performed very often. Several times it has happened that we have tried to put these on if we can find an opera house that would take the risk, which is very difficult nowadays, especially in this country, because the public is unhappily not curious. I must say this is something that here there are performers, singers and actors, who are at such a level, and I wish the public would be at the same level.

ML: But you see it really depends. I’ve never dreamt of staging Clari by Halévy, never. I didn’t even know it existed. But working on it with Cecilia was a wonderful artistic adventure, it really was. The Hamlet of Ambroise Thomas - probably not the best music in the world but a very decent opera, but to do it with Natalie Dessay at the time and Simon Keenlyside 13 years ago (pictured right © Catherine Ashmore) was a very interesting artistic adventure. Betrothal in a Convent – all kinds of pieces that you are proposed by an opera company. But there were pieces that we were proposed that we said, “No, thank you very much.”

ML: But you see it really depends. I’ve never dreamt of staging Clari by Halévy, never. I didn’t even know it existed. But working on it with Cecilia was a wonderful artistic adventure, it really was. The Hamlet of Ambroise Thomas - probably not the best music in the world but a very decent opera, but to do it with Natalie Dessay at the time and Simon Keenlyside 13 years ago (pictured right © Catherine Ashmore) was a very interesting artistic adventure. Betrothal in a Convent – all kinds of pieces that you are proposed by an opera company. But there were pieces that we were proposed that we said, “No, thank you very much.”

Could I return to the issue of the British lack of curiosity?

PC: I’m not really sorry to have said that, because that’s what I feel strongly. We have been a lot in this country and there is a wonderful public. The people come. But why aren’t they more curious about pieces? A company like the Welsh are condemned to do always the same titles. It is very sad. And to take a chance with another opera is really difficult for them because the audience doesn’t follow.

ML: We are not running these companies so we don’t come with solutions. But it’s like you would take a Mona Lisa, a Guernica and 10 other very famous paintings, put them in one museum and close all the other museums and you just have a museum with 10 pictures. It’s ridiculous. I mean there are so many operas. Why stick to the three, four, five, 10 mainstream titles?

Do you therefore feel constricted that you have done these three Rossinis here?

ML: No absolutely not, because I don’t think that – Barbiere, yes, but Cenerentola and Turco certainly are not operas that are done a lot.

What would you like to do here?

ML: I would l love to be able here to show another aspect of our work because we’ve been asked here mainly to do the Rossini and, God, am I grateful that we have been able to do that because I really adore Rossini. I adore it. But it’s true that it would be nice to be able to show another side of what we do. So it’s true that whether it’s German opera, contemporary stuff...

PC: Pélleas...

ML: Pélleas or whatever. Just between quotation marks "serious dramatic work". I adore the comedy of Rossini but - comment dire? - they tend to market us here with our “characteristic wit”. And you go, it’s not wit that characterises our work. Our work is not about wit. There is wit because there is wit in Rossini so our job is to bring out the wit of Rossini but it’s not our "characteristic wit".

If you could sum it up, what is your work about?

PC: To say our relation to the score. We both really love music: it’s to translate stage-wise how we hear it.

ML: It’s about how to make perceptible to an audience nowadays what the scream or the laughter of a composer is. That’s what it is about. It’s to make sure that the composer is still heard.

Do you find it easier to work in English or French? Does that inhibit you?

PC: No.

ML: We’re so used to it. We work in English and German.

PC: In Italian.

ML: We haven’t worked a lot in Italy – thank God for the nervous system.

PC: But sometimes we have to speak with Italian singers. Even in Russian. I mean anything goes.

ML: French, German, English - if you don't have these three languages there’s no point. But the discussion we’re having about interpretation of music, you can come as a director and ask a singer, “You have to be more nervous there.” Well, yes of course a singer can understand that. But if you go and say, “Your staccatos are not nervous enough, use the staccatos to work on the nervousness,” it’s a language that the singer, because he is a singer, will integrate and the nervousness will come through. All our work is about where to find the origin both of the acting and of the singing. That’s actually what we’re after. And what we’re after is thought.

- View theartsdesk's gallery of Royal Opera productions directed by Caurier and Leiser

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Le nozze di Figaro, Glyndebourne review - perceptive humanity in period setting

Mostly glorious cast, sharp ideas, fussy conducting

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Fidelio, Garsington Opera review - a battle of sunshine and shadows

Intimacy yields to spectacle as Beethoven's light of freedom triumphs

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Dangerous Matter, RNCM, Manchester review - opera meets science in an 18th century tale

Big doses of history and didaction are injected into 50 minutes of music theatre

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Mazeppa, Grange Park Opera review - a gripping reassessment

Unbalanced drama with a powerful core, uninhibitedly staged

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Saul, Glyndebourne review - playful, visually ravishing descent into darkness

Ten years after it first opened Barrie Kosky's production still packs a hefty punch

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

Così fan tutte, Nevill Holt Festival/Opera North review - re-writing the script

Real feeling turns the tables on stage artifice in Mozart that charms, and moves

La Straniera, Chelsea Opera Group, Barlow, Cadogan Hall review - diva power saves minor Bellini

Australian soprano Helena Dix is honoured by fine fellow singers, but not her conductor

La Straniera, Chelsea Opera Group, Barlow, Cadogan Hall review - diva power saves minor Bellini

Australian soprano Helena Dix is honoured by fine fellow singers, but not her conductor

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

The Queen of Spades, Garsington Opera review - sonorous gliding over a heart of darkness

Striking design and clear concept, but the intensity within comes and goes

The Flying Dutchman, Opera Holland Park review - into the storm of dreams

A well-skippered Wagnerian voyage between fantasy and realism

The Flying Dutchman, Opera Holland Park review - into the storm of dreams

A well-skippered Wagnerian voyage between fantasy and realism

Il Trittico, Opéra de Paris review - reordered Puccini works for a phenomenal singing actor

Asmik Grigorian takes all three soprano leads in a near-perfect ensemble

Il Trittico, Opéra de Paris review - reordered Puccini works for a phenomenal singing actor

Asmik Grigorian takes all three soprano leads in a near-perfect ensemble

Faust, Royal Opera review - pure theatre in this solid revival

A Faust that smuggles its damnation under theatrical spectacle and excess

Faust, Royal Opera review - pure theatre in this solid revival

A Faust that smuggles its damnation under theatrical spectacle and excess

Add comment