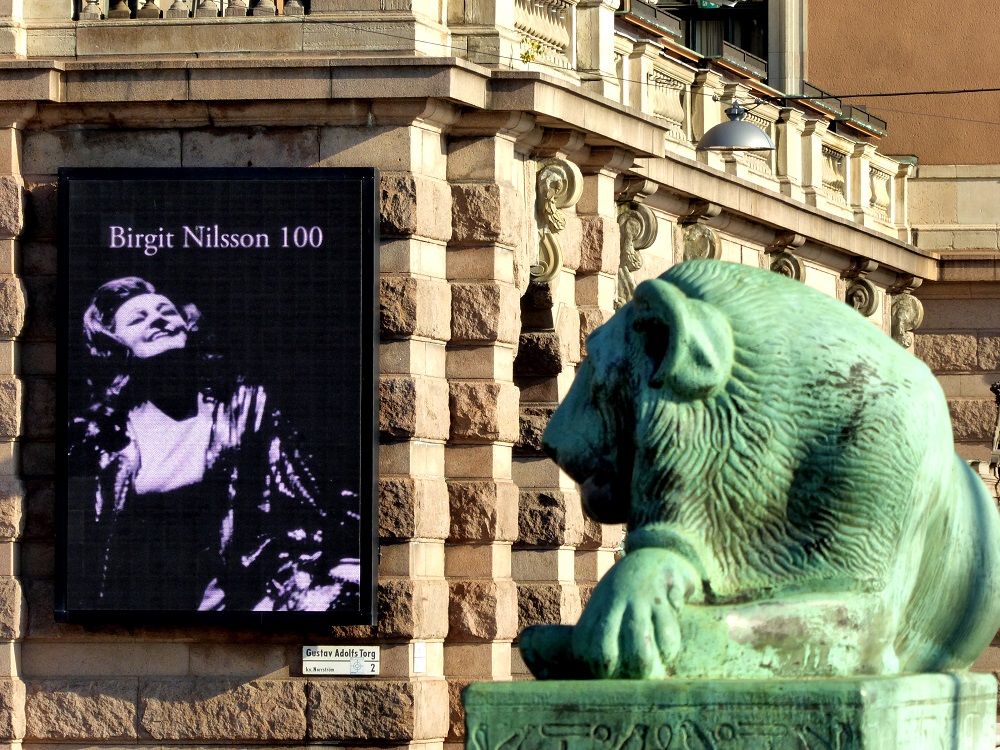

Why are great Wagnerian singers the most down-to-earth and collegial in the world of opera? Perhaps you have to be to master and sustain the biggest roles in the business, ones which can't be performed in isolation, and a strong constitution helps, too. Birgit Nilsson, the farmer's daughter born in rural Sweden 100 years ago, had all those qualities and many more. So, too, does her compatriot and one-time disciple Nina Stemme, making her perhaps the most appropriate laureate of the Birgit Nilsson Prize in terms of carrying on the line (the previous recipients at various intervals since the prize was first awarded in 2009 have been Plácido Domingo, Nilsson's nomination before her death; Riccardo Muti; and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra).

The day after a spectacular awards ceremony and banquet in Stockholm arranged by the Birgit Nilsson Foundation, using the bequest in the classiest way imaginable, I asked Stemme - currently singing Brünnhilde in four cycles of "the London Ring" - whether she would agree with the "collegial" statement; after all, her Siegfried, Stefan Vinke, certainly had, as he told me in a Wagner Society “audience with…” the previous Saturday, citing only one soprano among a cohort of colleagues to have been in any way difficult or diva-ish. Stemme had one similar experience, “but that was in a smaller-scale context and a long time ago. So I think when you've reached this level, of the Nordic gods, we all stand very close together. If you compare colleagues in an Italian context with Wagner and even Strauss, it can be a little bit more competitive between colleagues, but then those operas, especially Verdi’s, are written that way. And there's a challenge and excitement about the competition.  “Actually I feel now in Wagner a little bit the same, that we have a positive challenge between us, I and Stuart [Skelton, the Siegmund in the Royal Opera Ring] on stage, or I and John Lundgren, the Wotan, and even with Karen Cargill [currently singing Waltraute, Brunnhilde’s sister Valkyrie], it's fun and it's this test, this edge - because of course it's not meant like competition, but…” One person inspires the other? “Yes, it's not that one wants to be better than the other, it's like, how can we tell the story in the most exciting way. But at the same time offstage, we know that these parts are such gigantic mountains to climb, and we have to support each other. I've always found this so wonderful, all the way back to when I was singing Freia in Bayreuth, I could see that these people really care for each other, and we want the best from each other, which is very good, because Wagner and Strauss operas are too difficult to perform otherwise.”

“Actually I feel now in Wagner a little bit the same, that we have a positive challenge between us, I and Stuart [Skelton, the Siegmund in the Royal Opera Ring] on stage, or I and John Lundgren, the Wotan, and even with Karen Cargill [currently singing Waltraute, Brunnhilde’s sister Valkyrie], it's fun and it's this test, this edge - because of course it's not meant like competition, but…” One person inspires the other? “Yes, it's not that one wants to be better than the other, it's like, how can we tell the story in the most exciting way. But at the same time offstage, we know that these parts are such gigantic mountains to climb, and we have to support each other. I've always found this so wonderful, all the way back to when I was singing Freia in Bayreuth, I could see that these people really care for each other, and we want the best from each other, which is very good, because Wagner and Strauss operas are too difficult to perform otherwise.”

At the press conference held, like the individual interviews, in the gold-and-mirrors opulence of the Royal Opera House’s Royal Foyer, the inevitable question – what was the laureate going to do with the prize money? – was firmly met by Rutbert Reisch, the lifelong devotee of Nilsson’s art whom she asked to become President of the Foundation: Nilsson had stressed that there were no strings attached to the Award, and since the perfomer’s work itself did more for peace than the Nobel Prize, whose winners were never asked the same question, why worry how the sum was to be spent? Even so, though Stemme’s own answer has been that she needs to think about it – quoting the maxim of Richard Strauss’s Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, “jedes Ding hat seine Zeit,” “each thing has its time” – the likelihood is that she will invest it in the greater good.

There is, besides, in the listed criteria of the Birgit Nilsson Prize, in the “desirable” as opposed to the “obligatory” category, “an engagement in timeless humanitarian issues, albeit not of a political nature”. What’s political is questionable in the current upheaval, but I’d heard that Stemme, who had worked with Valery Gergiev, had strong words in one interview for his endorsement of Putin. As a campaigner against his unforgivable response to Putin’s crackdown on gay rights in Russia – “this is not about homosexuality, this is about paedophilia. In Russia we protect our children” – I asked her about this. “When the laws changed there, my own children were younger. It was a personal thing: could I be responsible for that when I didn't know what their preferences might be? Also, as Wagner performers, we sing for free love on earth…” I’d also heard that Stemme had supported a gay Ugandan who wanted Swedish support for a new life with his partner. “He is now to become a Swedish citizen, though sadly they've separated. It’s a network and expanded family sort of thing. I wish I had more time to spend on it. But yes, I do give active help. If you can do a little thing for one person, if everyone could do that, imagine what we could achieve together.” Spoken like the best of Swedes.

I’d also heard that Stemme had supported a gay Ugandan who wanted Swedish support for a new life with his partner. “He is now to become a Swedish citizen, though sadly they've separated. It’s a network and expanded family sort of thing. I wish I had more time to spend on it. But yes, I do give active help. If you can do a little thing for one person, if everyone could do that, imagine what we could achieve together.” Spoken like the best of Swedes.

Another true Mensch was performing at the Award Ceremony. These events can feel rather formal, given the silence that follows the arrival of the King and Queen of Sweden (pictured above, King Carl XVI Gustaf making the presentation to Stemme). Stemme’s radiant presence, American singer Mary Beth Peil’s presentation and very charming, palpably sincere speeches by Susanne Rydén, President of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music which is to take charge of the Foundation, and by a great former Erda, Birgitta Svendén, CEO and Artistic Director of the Royal Swedish Opera – these great Swedish women in high positions! – all helped to break the ice very quickly. No living performer, though, could dissolve the usual barriers between opera singers and audience more profoundly than Bryn Terfel, a charismatic Wotan to Stemme’s Brünnhilde.

In three testing operatic monologues, he went straight to the heart of the matter. His Flying Dutchman came from the shadows at the back of the stage, alongside the Royal Swedish Orchestra conducted by promising Wagnerian Evan Rogister, to turn a forbidding presence into lacerating, tormented humanity. Hans Sachs, meditating in the summer night on young Walter's gift of unusual melody, took off a shoe and set to work on it (excerpt above). Terfel's gouty Falstaff, asking whether honour could "set to" various parts of the anatomy, set about Herr Reisch and even gestured towards the Queen’s foot. All this with economy of gesture, a lesson in how to characterise without going too far, and setting it all up within a minute of each set piece.

An unflappably natural and friendly personage at the gala dinner in Stockholm’s Grand Hotel, Terfel handed over the post-prandial entertainment to no less a master in another field than Leif Ove Andsnes (pictured below with Reisch), whose Chopin "Military" Polonaise caught the buoyancy of the occasion to perfection. Sweet treats, one especially christened “La Nilsson” with culinary homage to the Nilsson family farm in Skane, came from pastrymaster Joel Lindqvist and Rickard Söderberg, winner of Sweden’s Celebrity Bakeoff, tenor and champion of LGBT rights, a glamorous presence at Royal Opera evenings – I’ve seen him there before – and at the banquet. Great Swedish baritone Peter Mattei was among the guests; their majesties sat at the top table with the evening’s stars.  Every little detail of these stunningly well-planned celebrations was done with care and no expense spared, down to the ticket wallet and the cards for various bills of fare. We even had a privileged tour of the Nationalmuseum’s collections two days before the place was due to re-open to the public following a five-year restoration programme; far too much to describe here, but I’ve written about the experience elsewhere (see link below). As for the after-effects of all this, set in motion by La Nilsson herself and thanks to both Reisch and the Foundation, they continue to give: a much-need republication of the English translation of Nilsson’s feisty autobiography, the most luxuriously-produced of picture books, a DVD revealing why we should love Nilsson the human as well as the semi-divine artist, and a 31-CD Sony box of remastered live performances, including three Tristans and two Elektras. That’s the thing about the handful of truly great performers: there can never be an end to the legacy.

Every little detail of these stunningly well-planned celebrations was done with care and no expense spared, down to the ticket wallet and the cards for various bills of fare. We even had a privileged tour of the Nationalmuseum’s collections two days before the place was due to re-open to the public following a five-year restoration programme; far too much to describe here, but I’ve written about the experience elsewhere (see link below). As for the after-effects of all this, set in motion by La Nilsson herself and thanks to both Reisch and the Foundation, they continue to give: a much-need republication of the English translation of Nilsson’s feisty autobiography, the most luxuriously-produced of picture books, a DVD revealing why we should love Nilsson the human as well as the semi-divine artist, and a 31-CD Sony box of remastered live performances, including three Tristans and two Elektras. That’s the thing about the handful of truly great performers: there can never be an end to the legacy.