Frank Johnson, the great parliamentary sketch-writer who died in 2006, was a passionate fan of opera and ballet. While intensely admiring certain artists, he kept eye and pen sharp for his observations of cultural matters, mocking cabals of opinion-formers in the arts as ruthlessly as he quilled politicians. These extracts from a newly published collection of his writings, edited by his widow Virginia Fraser, show both sides of him.

5 March 1989: Benjamin Britten's whimsicalities

As an impressionable youth in the 1950s and early 1960s, I endured the unceasing propaganda of the nation's arbiters of taste about Benjamin Britten being a great operatic composer.

True, much of this agitation was the work of what might be termed the homosexual school of music criticism: certain post-war critics who were gay before their time. What was Britten's swooning Billy Budd if not the all-male Madam Butterfly - though without the same melodic inspiration? But articles in the influential magazine Opera, which was under broadly heterosexual control, would routinely throw Britten into the succession of acknowledged greats: "... Mozart, Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, Strauss, Janacek, Berg and Britten."

True, much of this agitation was the work of what might be termed the homosexual school of music criticism: certain post-war critics who were gay before their time. What was Britten's swooning Billy Budd if not the all-male Madam Butterfly - though without the same melodic inspiration? But articles in the influential magazine Opera, which was under broadly heterosexual control, would routinely throw Britten into the succession of acknowledged greats: "... Mozart, Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, Strauss, Janacek, Berg and Britten."

In his autobiography, Lord Harewood, founder of Opera (magazine) and later the English National Opera Company's managing director, is unrelenting on the subject of Britten's tenor companion, the late Sir Peter Pears - he of the strangulated high tones, curdled lower ones, and general whooping. Pears, says Lord Harewood, was "the peer of Callas... the inspiration of Benjamin Britten... He would have been King Lear if Britten had written it."

Nowadays, one unashamedly regards the loss of Britten's Lear, starring Sir Peter, as a lucky near-miss. But, at the height of the Britten-Pears Terror, it was not so easy. I began to believe in Britten's greatness myself.

The rest of the world, however, decided differently. Britten's operas are not much performed abroad. There will still be people for whom Britten's whimsicalities and maunderings will be profound and beautiful. But they will mainly be British. (Sunday Telegraph)

11 June 1989: Domingo "has improved", Pavarotti announces

Next Sunday, Luciano Pavarotti will give a concert in the new London Arena. The following night Placido Domingo will complete five performances of Il Trovatore at Covent Garden. People who know nothing about opera know one thing. Those are the world's two greatest tenors. But if they are, why? Domingo and Pavarotti, in strictly alphabetical order, are "great tenors" as the term is popularly understood (not that this detracts from their greatness). They are associated with the sound which most people, whether they like it or not, seem to recognise as the sound a great tenor is supposed to make. That this sound became the world's idea of the tenor was not inevitable. It was because of Caruso (1873-1921). He began a line which continued through Gigli (1890-1957) to the present.

Domingo was born in Madrid, in 1941, and Pavarotti at Modena, in 1935 - though there is a school of thought which claims that Domingo is just as old as Pavarotti. Domingo was the son of singers of zarzuelas: Spanish light operas. Pavarotti's father was a baker, who had been in the local opera house chorus.

The big difference between the two is that Domingo began his career in the lower category of voice: baritone. Domingo's voice is darker. Pavarotti avoids the heaviest Italian part, Verdi's Otello, and Domingo avoids high Cs; though that leaves plenty of other parts and notes which they have in common.

Domingo's variety of parts is far greater. He learns them very quickly. He is the better - certainly the slimmer - actor. Domingo is the tenor for opera-goers who take the "serious" stage seriously - who go to the National Theatre, and the Barbican, and regard the director as being at least as important to performance of Italian opera as the singers.

The world has never before been reduced to just two "great tenors". (There is a case for another Spaniard, José Carreras, as a third. But even before his recent struggle with leukaemia he was punishing his beautiful voice by singing parts too big for it.)

When asked about one another, Domingo and Pavarotti adopt the courtesies which people use when they do not approve of each other. Ever since he was first conscious in the late '60s that Domingo would be his lifelong rival, Pavarotti has used the same formula: "Placido has improved." Pavarotti is conscious that - being the Italian - he has the advantage. His sound is simply more authentic.

A great authority on singing once wrote that when Everyman sang in his bath, it was Caruso whom he fancied he heard. As we have seen, some fine social distinctions exist between the supporters of today's great two. Whether it rings with Domingo or Pavarotti can tell us a lot about a man's bathroom, and the man. (Sunday Telegraph)

1 April 2000: Harold Pinter (1930-2008): The Chekhov of the working class

I have never been able to think of Pinter plays, as so many of both his admirers and detractors do, as unrealistic. We read that Chekhov caught to perfection the speech of the minor Russian country gentry. Pinter is the Chekhov of the London proletariat. To me, as a Londoner from roughly the same part of the city as Pinter, the non sequiturs of the following passage from The Caretaker were what I heard all the time from relatives and neighbours: "You remind me of my uncle's brother... Very much your build. Bit of an athlete. Long-jump specialist. He had a habit of demonstrating different run-ups in the drawing room round about Christmas time..."

Why round about Christmas time? the logical middle-class mind might ask. But Londoners scorn such literalism. The character does not elaborate on why that particular season, but continues: "Had a penchant for nuts. That's what it was. Nothing else but a penchant. Couldn't eat enough of them. Peanuts, walnuts, Brazil nuts, monkey nuts, wouldn't touch a piece of fruitcake. Had a marvellous stopwatch. Picked it up in Hong Kong. The day after they chucked him out of the Salvation Army. Used to go in number four for Beckenham reserves... Had a funny habit of carrying his fiddle on his back."

The same character has another immutable passage: "You've got a funny resemblance to a bloke I once knew in Shoreditch. Actually he lived in Aldgate... When I got to know him I found out he was brought up in Putney. That didn't make any difference to me."

Persons of an unimaginative, bourgeois cast of mind might object: why on earth would it make a difference to him? But the character presses on: "I know quite a few people who were born in Putney. The only trouble was, he wasn't born in Putney, he was only brought up in Putney. It turns out he was born on the Caledonian Road just before you get to the Nag's Head. His old mum was still living at the Angel. All the buses passed right by the door. She could get a 38, 581, 30 or a 38A, take her down the Essex Road to Dalston Junction in next to no time. Well, of course, if she got the 30 he'd take her up Upper Street way, round by Highbury Corner and down to St Paul's Church, but she'd get to Dalston Junction just the same in the end."

Passages like this can still be overheard on tubes and buses from a certain generation. Pinter wrote The Caretaker at 30. At nearly 70, he has lost none of his gift for creating real Londoners. His new play, Celebration, captures the speech of those who have moved out to Essex and become rich: the self-made Thatcherite wealthy whom Mr Blair won over in 1997 by promising no higher taxes. It is to be doubted whether Pinter has met any of them, but he knows them. He is a genius of language as well as a genius in general. Would that there was a Pinter of the distinctly non-cockney world in which Pinter now moves. Perhaps, in his next play, it will be Pinter. (Spectator)

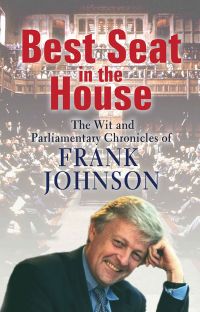

- ‘Best Seat in the House: the Wit and Parliamentary Chronicles of Frank Johnson', edited by Virginia Fraser, is published by JR Books in hardback at £18.99. Buy online here

- Domingo sings the baritone lead in Verdi's Simon Boccanegra at the Royal Opera House next summer. Royal Opera House information here.

- Alfredo Kraus discusses 'the three tenors' on theartsdesk.com here

Add comment